Source: Wikipedia

Source: Wikipedia From Unakami Tomoaki’s “Hontō wa gokai darake no Sengoku kassen senshi”, Tokkan Shoten, Tokyo, August 2020

Tokugawa Ieyasu was a master of intrigue, but…

In much the same way at Oda Nobunaga, Tokugawa Ieyasu spent the first half of his life seeking to expand his rule. Despite being born as the lord of Okazaki Castle in Mikawa province and the legitimate heir to the Matsudaira family, he had been brought up since infancy as a hostage to both the Oda and the Imagawa families. At the Battle of Okehazama, while Oda Nobunaga was fighting against Imagawa Yoshitomo, Ieyasu was part of the Imagawa army. He was no more than a lad of 19 at the time.

When the Imagawa’s power began to decline following the Battle of Okehazama, Ieyasu made the decision to strike out on his own as lord of Okazaki Castle. It was at this time that he forged an alliance with Oda Nobunaga. For the next 21 years, until Nobunaga met his end during the Honnōji Incident, that military alliance would continue.

The Sengoku-era historian Taniguchi Katsuhiro noted that this alliance took place at a unique time in the Sengoku period, and whose mutual interest would continue for many years (Taniguchi Katsuhiro, “Nobunaga and Ieyasu’s Military Alliance – 21 years of interests and strategy”, Yoshikawa Kōbunkan, 2019).

Opposite the sphere of influence exercised by Imagawa Yoshimoto in Suruga province lay a region contested over by three major powers, namely the Hōjō, Takeda, and Uesugi families. Suruga province bordered these lands, and would eventually be amalgamated with Mikawa province. Owari province would see daily clashes over its border area. After Suruga lost its principal source of authority, a newly freed Ieyasu was able to start building a small power base in Mikawa. Meanwhile Nobunaga, in order to protect himself from the direct threat Takeda Shingen of Kai province presented to Owari province, realised that he needed Mikawa as a buffer zone.

For Ieyasu, he too wanted to receive aid from Nobunaga to both preserve his independence and prevent himself from once again being sucked into a power struggle against formidable opponents. Ieyasu made good use of his alliance with Nobunaga, and following the deaths of Nobunaga and Hideyoshi, he deposed their heirs and built the foundations for an era of peace that lasted some 260 years.

Despite all of this, Ieyasu was something of a military dunce. One thing that stands out in particular with regard to this is the epic Battle of Sekigahara that decided the fate of the nation. If you take a look at the disposition of the Eastern Army on the eve of the battle, such was Ieyasu’s lack of military skill that it is a wonder that the Western Army was not victorious. In much the same way as Nobunaga, Ieyasu suffered defeat on the battlefield time and time again.

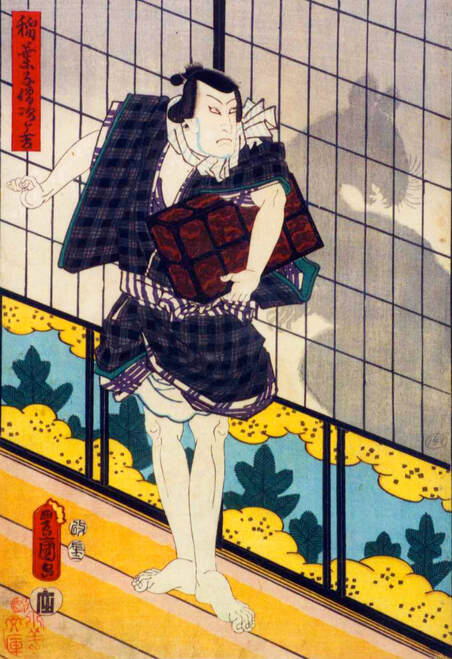

What Ieyasu excelled at was intrigue. While Nobunaga may have possessed a genius for revolutionary thinking, and of the three great unifiers it was Hideyoshi that was most capable militarily, Ieyasu was the strategist. He was also extraordinarily cautious. He had learned a lot at the hands of Takeda Shingen of Kai, who had always presented the greatest threat to Mikawa. His experience living as a hostage also meant that he had taken exercising a high degree of caution to heart. Two apocryphal tales that left an impression on me in this regard are the tale of the out of season peaches and the crossing of the Marukibashi bridge.

When Ieyasu was still a young man, Nobunaga sent some peaches to him. Under the old calendar this occurred in ‘Shimotsuki’, which in the modern calendar corresponds to December. While his retainers were perplexed as to how such a thing could have happened, and what sort of technology had been used to make it happen, Ieyasu pondered why Nobunaga had sent the peaches in the first place, and thinking that they might have a detrimental effect on his health, chose to give all of the peaches to his retainers. Hearing of this, Takeda Shingen offered his assessment, thinking “This is an individual that goes to great lengths to preserve his health. He prioritises his metabolism, and it appears that he won’t eat anything unnecessarily” (as recorded in the ‘Hisakankin’, a compilation of apocryphal tales about Tokugawa Ieyasu, edited by the Zenkoku Tōshōgu Rengōkai, published 1997). Shingen, who as a student of Sun Tzu had been able to correctly deduce Nobunaga’s nature, realised that far from being a dull and introverted soul, Ieyasu was in fact bursting with ambition.

Ieyasu was also known as a fine practitioner of the Ōtsubo school of horsemanship. However when attempting to cross a bridge spanning a river during the attack on Odawara during the Tenshō period, he deliberately got off his horse and crossed the river while being carried on the back of one of his retainers. Ieyasu hadn’t learned horsemanship in order to show off in front of others, but rather to allow him to escape from the battlefield and live to fight again. Hence he had no need for any adventures, which does make for rather a dull story (from the Jyōzan Kidan and Bushō Kanjyōki published by Hakubunkan in 1929).

Ieyasu’s high degree of caution made it impossible for him to achieve great deeds, but he possessed an extraordinary ability to wield intrigue. Figures such as Mōri Motonari, Hōjō Sōun, and to some extent (Hōjō) Ujiyasu were generals of the strategic type, prepared to put up with hardship for a while waiting for their chance to strike. Once their chance came they would move with lightening speed, but in the interim they would act cautiously, biding their time and building their resources. Ieyasu had the special patience of the strategist, and disliked embarking on adventures that would yield no rewards. It was impossible for him to understand why anyone would act purely out of desire to provoke a response. He was also far more concerned about his health than the ordinary person. His way of thinking, in which living a long life was what divided up life’s winners from its losers, was in contrast to Nobunaga and his idea that “life is but 50 years long”.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed