Chapter 12 The dramatic crimes of Nezumi Kozõ

When considering the types of crimes committed during the Edo period by so-called “noble thieves” (in Japanese, gizoku, referring to thieves who, out of a sense of righteousness and obligation, gave the money they stole to people in need), the name of Nezumi Kozõ (literally ‘Rodent Boy’) immediately springs to mind. Yet in truth there were other gizoku making a name for themselves before the arrival of Nezumi Kozõ. One of those is included in the twenty-second scroll of the “Kasshi Yawa” (Evening Tales of the First Lunar Cycle). (228)

At approximately 2pm on the 7th day of the 9th month of Bunsei 5 (1822), someone managed to sneak his way into the residence of the shõgunate retainer Yajima Genshirõ, a member of the retinue of Hikozaka Õmi no Kami and a member of one of the lesser band of principle retainers to the shõgunate known as the Kobushin.

This mysterious individual proceeded to help himself to some of the chests of drawers in which money, official documents and books were kept. He stole the lot – cabinet and all. (228)

Then at around 8pm on the 11th day, just four days later, someone heard the sound of an object hitting the house next door to Yajima’s. When a house retainer went to investigate, he found a ball made of paper and closed with a seal into which had been placed the official documents and ledgers stolen on the 7th, as well as a letter bearing the name of the man who had presumably stolen the items in the first place - ‘Kurata Kichiemon’. The chests of drawers were also later found abandoned under the walkway leading to the “Settchin” (雪隠, an otherwise poetic name for an outhouse or WC). (228)

On the 15th day of the 9th month, Yajima himself took the letter that had been inside the ball in hand and went to submit an official complaint to Hikozaka Õmi no Kami. Hikozaka then took that complaint to the town magistrate where he made his own request for an investigation.

So what had been stolen from Yajima’s house?

According to the complaint deposition, 37 ryõ (or taels) of gold were missing, along with two and a half ingots of pure silver and two of lesser grade silver, along with documents (namely debt certificates), one of which was worth 20 gold ryõ while four others were worth 15 gold ryõ. Another document had been taken worth 10 gold ryõ, along with ledgers and other books (titles and identification papers).

This thief, who went by the name of Kurata Kichiemon, had decided to take only the coinage since all of the other items were returned. His reasons for doing this were presumably because he had either been unable to convert the other items into money, or else he was worried that if he did something foolish and was caught, then these documents would serve as evidence that he had committed the crime (or he may have simply been following a trend among thieves to return any non-monetary goods to their owners). (229)

The letter from Kichiemon

So why was Kichiemon regarded as a gizoku? Whether or not there was any truth behind such a claim is debatable, however it was referred to in Kichiemon’s own letter. This itself was unusual - a thief writing a letter addressed to one of his victims.

Moreover the letter itself is overflowing with wit. I would be overjoyed to introduce the letter to the reader in its entirety, however this would be overly arduous as the letter is quite long. So in order to expedite proceedings I have only quoted the most relevant parts, and made my own modern translation of their content.

The letter is neither threatening nor insulting, and begins with an apology:

“I ventured to your residence upon learning that my lordship’s circumstances were indeed fortunate, and so sought to borrow some of your wealth. However after gaining entry, I found that you were not quite as wealthy as I had first imagined, and so for this I do offer my most sincere apologies.”

He then went on to explain his reasons for stealing the chests of drawers:

“I did not sneak into your residence for the purposes of personal gain. I simply could no longer stand to see the long-standing suffering of so many people. And so while I myself am poor, I realized that I could alleviate this suffering by borrowing (i.e., stealing) the money kept on your estate.”

Kichiemon himself confesses that his actions were for the benefit of other less fortunate people, thereby equating himself with a gizoku. Furthermore, he goes on to promise that he will eventually return the money that he had ‘borrowed’:

“I will return the money to you very soon, hence I ask that you be patient in the interim.” (231)

The above quotations cover the heart of the letter’s content, but the letter itself contains numerous long “post scripts”, where Kichiemon outlines his history as a gizoku and about his own personal circumstances:

“I have been taking the things of wealthy people in order to give to them to the poor for many years, but any money that I borrow (i.e., steal) is eventually returned. I am already in my 50s, but have not given up on life yet, and continue to live without want.”

In his post script, Kichiemon also offered some opinions about the locks and security of the Yajima residence (from an expert’s point of view):

“Your lordship’s house has excellent locks, but it seems that this has made your household complacent (i.e., they don’t seem to have noticed an intruder).” (233)

Enter the Gizoku

The above quotes came from the ‘Evening Tales of the First Lunar Cycle’, however we can find an alternative version of same events in the “Mikikigusa” (Tales Seen and Heard).

The first deals with the intrusion of the bedchamber of Tajima and his wife.

The ‘Evening Tales of the First Lunar Cycle’ simply states that Kichiemon “entered the couple’s sleeping quarters”. However the ‘Tales Seen and Heard’ says that Kichiemon “intruded upon the bedroom of the couple, but found that they were fast asleep. They both looked content, and Kichiemon regarded them with some envy”. (233)

Be that as it may, what prompted Kichiemon to write his letter in the first place? Firstly, if you write a letter, you create an important piece of evidence with details of your handwriting. A letter also offers you a way to confess if you have carried out similar crimes over a long period of time. It is, in a way, a form of self-advertising your crimes to draw attention to yourself. It also makes you a criminal with a flair for the dramatic, does it not? (234)

Speaking of dramatic crimes, one incident from the 1980s, the Glico-Morinaga extortion investigation, comes to mind. In the case of that incident, a person calling themselves ‘The Monster with 21 Faces’ issued threats against companies and their employees. In the case of Kurata Kichiemon, he advertised his crimes under the banner of a gizoku. (234)

The complaint made by Yajima and a copy of Kichiemon’s letter eventually found their way into the hands of the town magistrate. Other copies were handed to Matsuura Seizan (described in an earlier chapter) and Miyazaki Seishin (both of whom were famous writers of their day), and it is entirely conceivable that more copies were distributed to other readers. Each of those copies were then seen by unknown numbers of friends and family of the recipient, and so Kurata’s exploits as a gizoku began to be discussed and admired by a wider audience. As word spread, the content of these letters became more and more interesting, and it seems that people had started adding their own details in order to liven the story up. That may be the reason why details that were included in the ‘Tales Seen and Heard’ weren’t included in the ‘Evening Tales of the First Lunar Cycle’. (235)

Kurata Kichiemon – the 50-something year old thief. As a result of his hurling a letter into the residence of Yajima Genjirõ, he drew attention to himself and ended up becoming the lead character in plays based on the exploits of gizoku.

But what eventually became of Kichiemon himself? Sadly we have no idea. Whether he was a true gizoku and eventually returned the money that he had ‘borrowed’ will forever remain a mystery. (235)

Introducing Nezumi Kozõ

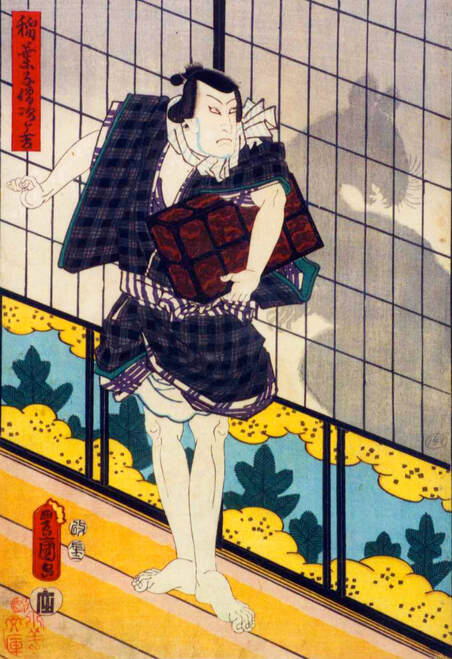

Speaking of drama, Nezumi Kozõ Jirõkichi must be the very definition of a theatrical ‘noble thief’. Before I explain why, I should provide some details about his life.

My sources for this include both the ‘Evening Tales of the First Lunar Cycle’ (scrolls 78 to 81), a collection of stories by the bookshop owner Yamashiro Yachûbei (titled Bunbõdõ Zassan, or ‘Miscellaneous Tales from Bunbõdõ’ (Bunbõdõ being the name of the shop). There is also the ‘A True Record of the Rodent Thief’ (Sozoku Hakujõki). As each record differs in content, I have decided to compile them together in the explanation that follows. (235)

Nezumi Kozõ Jirõkichi was put to death at the age of 36 in the 8th month of Tenpõ 3 (1832). Assuming that the record of his age at the time of his death is accurate, this would put his year of birth in or around Kansei 9 (1797). He was born in Shin Izumi-chõ, an area that is now part of Ningyõ-chõ, 3 chõme in central Tokyo. His father was Sadajirõ, a dekata, or theatre usher working in a Kabuki theatre (and occasionally playing minor roles such as a youth, or Kido-gashira, of the type performed by the Nakamura-za (theatre) of Sakai-chõ). Sadajirõ was apparently blind in one eye, which led to him being called ‘one-eyed Sada’ (he was also called ‘squinty’ because of his supposed short-sightedness). He died of illness in Bunsei 12 (1829), about ‘four years’ (actually three years) before Jirõkichi was executed. (236)

When he was 14 years old, Jirõkichi commenced work for a cabinet maker (who built other wooden objects as well) located in Kameda Konya-chõ (modern day Chiyõda-ku Kameda Konya-chõ in Tokyo). However he engrossed himself in bouts of gambling to which he became addicted. He quit working at Kameda and hired himself out as a temporary assistant to another cabinet maker located beneath a watch tower along the banks of the Hettsui-gashi river (now part of Nihonbashi, Ningyõ-chõ, 2 chõme). Yet Jirõkichi’s passion for gambling remained unquenched, and when he was 16 he moved back in with his parents. (236)

It was while he was living with his parents that he was hired by another cabinet maker, in whose service he came to work on the residence of a falconer for a samurai household. This falconer saw talent in the boy and so hired him as an apprentice. Yet this is no way convinced Jirõkichi to go on the straight and narrow. His desire for money to use on entertainment and gambling was too strong to resist, and so in Bunsei 6 (1823), at the age of 26, Jirõkichi decided that he would start robbing the houses belonging to samurai (and even daimyõ) families. (237)

But why on earth would he choose to rob samurai households? The reason, it seems, lay in the degree of concern that samurai displayed in relation to safeguarding their wealth. Townspeople (i.e., merchants) were normally quite afraid of burglars, and so would use every means possible to ensure that their money was secure from theft. Samurai, on the other hand, while they might have used tight security on the outside, tended to have fairly lax security once you were able to traverse the moats surrounding the house and gain entry to their inner sanctum. (237)

Jirõkichi had been adept at walking in high places since he was a little boy, so much so that all he needed to do was grab hold of something in order to climb it, no matter how dangerous it might be. Furthermore, many samurai households had quarters at their centre that were for the exclusive use of the women of the household, who also oversaw their own security for those rooms. Jirõkichi figured that since no male samurai could easily enter that part of the house, he stood a much better chance of being able to rob the house without exposing himself to too much danger if he started in the women’s quarters. (237)

And so, from the 2nd month of Bunsei 6 through to the 1st month of Bunsei 8, Jirõkichi proceeded to rob the households of daimyõ no less than 30 times.

However, luck is a fleeting thing. On the 3rd day of the 2nd month of Bunsei 8, Jirõkichi was spotted while trying to break into the household of one Tsuchiya Sagami no Kami (lord of Tsuchiura in Hitatchi province), and was later captured by a posse belonging to the local magistrate, one Tsutsui Iga no Kami (Masanori) of Minami-chõ. Jirõkichi would not admit to having robbed anyone, and so was taken to Moto Osaka-chõ (now Nihonbashi, Ningyõ-chõ 1 chõme) on the 14th, where he was imprisoned as ‘Jirõkichi of the Senkichi-ten’ (or shop). (238)

It was while he was under arrest that Jirõkichi was questioned about his motives, and so gave the following statement:

“Since the 8th month of last year, I have been involved in gambling bouts against peasants and merchants of between 100 to 200 bun (equivalent to around 32.5 yen) at various places including Senju (part of modern Adachi-ku in Tokyo). At these places I have indulged in games like mawari-zutsu (‘spinning the pipe’), chohan(odds and evens), and chobo-ichi (snake eyes). When I went to visit a friend of mine called Yasugorõ on the 3rd day of the 2nd month at the (Tsuchiya) household, I wasn’t able to meet him. So my wicked nature took over and I decided to rob the place”. (238)

Despite not actually haven taken anything from the household, a complaint was filed against Jirõkichi, and so on the 2nd day of the 5th month, he was sentenced to first be tattooed (thus marking him as a criminal) and then to be banished from Edo to a ‘middle distance’ from the city (in the case of commoners, this meant that a person could not commit a crime or enter any territory in the four directions extending ten ri (between 32 to 40 kilometres) from Edo itself). (238)

Another tale also exists regarding Jirõkichi’s attempted break-in at the Tsuchiya household. According to this story, when Jirõkichi entered the quarters of the former ruler of Tsuchiura (known as an Inkyõ. In samurai households, it was not unusual for former rulers to co-habit with the current ruler in order to serve as an advisor and mentor) he was seized by one of the former ruler’s guards. When Jirõkichi was being handed over to the town magistrate, the Inkyõ had a change of heart, and so paid the 10 ryõ bail money to let Jirõkichi go free. But why would he do this?

Apparently Jirõkichi was quite adept at lying, and had told the old man that ‘I am taking care of my sick mother, and am living in the depths of poverty’. (238-239)

After being banished from Edo, Jirõkichi spent some time in the Kyoto area (one source says that he spent half the year on a pilgrimage to Konpira shrine). However he soon drifted back again, and so broke the law. He changed his name to Jirõbei, and again took up living with his parents. His tattoo mark would obviously become a problem if discovered. So after asking a certain Kanejirõ for assistance, one of his old acquaintances from his time as a falconer in the samurai household, he managed to have the tattoo modified by disguising it under depictions of clouds and dragons, thereby keeping his criminal past a secret. (239)

Jirõbei (as we will now call him) then changed his living address to Yujima 6 chõme, and took up an ostensible trade selling steamed vegetables. His real profession, however, remained gambling. Before long Jirõbei again found himself short on funds, and so reverted to the one sure-fire way to redress this problem – stealing from samurai households. From the time he managed to break into the residence of Matsudaira Daigaku no Gashira (lord of Moriyama in Mutsu province) sometime during 7th month of Bunsei 8, until his arrest on the 4th day of the 5th month of Tenpõ 3 (1832) after attempting to rob the residence of Matsudaira Kunaishõ-yû (lord of Obata in Kõzuke province), Jirõbei conducted over 80 burglaries on various samurai households. Following his arrest, he was eventually handed to city authorities on the 19th of the 8th month of Tenpõ 3 and imprisoned.

It was believed that in all, Jirõbei had carried out over 100 burglaries, with a combined loot value of over 3,100 ryõ. (239)

A talent for lying

Having been born on the narrow streets of Edo, filled with its theatres and tea houses, Jirõbei was almost certainly influenced by these, if not also by his theatrical father. Nezumi Kõzõ Jirõkichi (back to that name once again) was the city equivalent of Inaka (or rural) Kõzõ (another famous robber of his day), and had just enough theatrical ability to make him a star in the role of a theatrical villain. Of course, when I say theatrical ability, what I mean is that he had a particular talent for telling fibs. The truth is that Jirõkichi was not only talented at making his way across moats and scaling walls to enter daimyõ households, he also had a distinct knack for being able to lie his way out of trouble. (240)

Matsuura Seizan managed to get hold of a copy of the confession Jirõkichi made to another of Matsuura’s compatriot officials, one Ueda Bõ. He then included this in his ‘Evening Tales of the First Lunar Cycle’ (in the eighty-first scroll containing edits), and it is from this that I will draw the following quotes. I should also add that there are many records and tales in existence in regard to Nezumi Kozõ, and so it is particularly difficult to judge which are reliable and which are not. Yet for all that, a deposition created by a city official based on a direct confession should probably be regarded as trustworthy. (240)

- About ten years ago, as I was passing through the front gate of the residence belonging to Arima Genba no Kami (lord of Kurume in Chikugo province), I lied that I had some business with the falcon coop keeper, and so was allowed to enter the household grounds. Later that night, I stole around 5 ryõ worth of gold from the room belonging to the chief retainer to the women’s quarters.

- Around ten years ago, as I passed through the front gate of the residence of Lord Mito (one of the three great Tokugawa households), I told the guards on duty that I had business in the ‘Edo room’ and they let me in. Later on, I stole around 70 ryõ in gold after sneaking into the room of the chief retainer of the women’s quarters.

- Four or five years ago, as I made my way through the entrance gate to the residence of Matsudaira Izumi no Kami (lord of Nishio in Mikawa province), I told the guards on duty that I was a demawari (a close retainer to the lord of the household) so they let me in. Afterwards I stole 25 ryõ in gold.

- Seven or eight years ago, as I was making my way through the front gate of the residence of Hosokawa Etchû no Kami (lord of Kumamoto in Higo province), I told the guards on duty that I had business in the quarters of retainers to the absentee (or rusu, 留守) official (essentially a senior minister of the household and personal retainer to the household lord who acted in his lord’s stead when the lord was absent). I was allowed to enter, and stole 2 ryõ’s worth of gold from the chief retainer to the women’s quarters. (240-242)

With Jirõkichi’s level of acting skills, getting past the guards out front was a piece of cake. He approached each gate honestly and openly, saying ‘Look, I’ve got an appointment with such-and-such, so how about letting me through?’. (242)

To be continued.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed