Source: Utagawa Kuniyoshi "Soma no Furudairi", circa. 1842

Source: Utagawa Kuniyoshi "Soma no Furudairi", circa. 1842 “A popular trend from the mid-Edo period onwards was the telling of “one hundred tales of terror”. In the evening, adults would gather together, with participants telling between 4 to 5 horror stories each. In the centre of an otherwise dark room were placed 100 candles, lit one after another, the light from which shone on the candle trays supporting them. Once a tale had been told, a single candle would be put out so that the room grew progressively darker. By the time of the witching hour (around 2 in the morning), all 100 tales had been told. Upon the extinguishment of the last remaining candle, creatures of the night would instantly emerge from all directions, making such gatherings a kind of ‘monster viewing’ party.

However, it was common practice to refrain from telling the hundredth tale. Superstition had it that if the hundredth story was told, misfortune would befall whomever had spoken it. People were afraid that they would regret having told the hundredth tale, and so avoided doing so.

In truth, there was a very clear distinction between “monsters” and “ghosts”. ‘Ghosts’ appeared to a specific person and would deliberately seek that person out. The character of “O-Iwa san” from the Tale of Yotsuya by Tamiya Iemon was one example of this.

‘Monsters’, on the other hand, would attach themselves to objects and the elements of the natural world, similar in manner to a haunting, and from there would appear to anybody who happened to be passing by. One example of this was “O-Kiku san” from the “Sara Yashiki Densetsu”, and whose modus operandi consisted of emerging from a well. There were also monsters who only appeared at fixed times, and so you would be able to avoid them if you refrained from passing their haunting ground during certain hours of the day or night.

‘Monsters’ consisted of many different forms – from animals such as foxes, badgers, and sparrows, to trees and grass. Many ancient tales of Japan had monsters made musical instruments and common household objects such as Koto harps, Biwa lutes, Sheng (or Shō) mouth organs, and even cauldrons. Their purpose was to serve as a lesson to “look after your possessions”.

‘Monsters’ were divided up into those that transformed and those that didn’t. Badgers, foxes, ‘snow woman’, and ‘Rokuro-kubi’ (the ‘long-necked woman’) were all examples of everyday people and animals that could undergo transformation. By contrast, ‘Kappa’ (water sprites), ‘Tengu’ (forest goblins), ‘Nurarihyon’ (“the old monk with the elongated head”), and ‘Suna-kake Baba’ (the “old woman who throws sand”) all appeared as they were. They constituted a separate category to “monsters”, which is why they were referred to as ‘Yōkai’ (or ‘creatures’).

‘Monsters’ lived in close proximity to the townspeople of Edo. One of these, known as the ‘Adzuki Bean Washer”, didn’t do anything nefarious at all, merely producing a noise of adzuki beans being washed. One would think it better to wash rice, but it appears this was a no-no.

One ‘monster’ that appeared in an unclean public bath was “Akaname” (or ‘filth licker’), who would turn up to lick the dirt and other debris out of a bathtub. The lesson to be learned from this was “keep your bathtubs clean, otherwise a ‘monster’ will appear”.

Another ‘monster’ was ‘Nebutori’, an immensely overweight woman who slept on a pile of cushions. The lesson here was “if you are lazy, then this is what you’ll become”.

Around the Honjō area there were a large number of canals (or ditches, if you like). One of these was the infamous “Oite kebori”, although since a canal by this name was never specially designated, it seems that any canal into which someone cast a fishing line could be classified as an “oite kebori”.

If you spent all day trying to catch fish and ended up on the canal bank as it grew dark, it was said that the spirit of the canal would command you to “leave, leave!” (or 置いてけー、置いてけー!) . If you chose to leave then you would be fine. However if you chose to stay, then some misfortune would later befall you, or all of the fish that you wished to catch would disappear. This served as a warning not to get carried away in catching fish, and also prevented any water-related accidents around the canal. When it grew dark, there was a greater risk of stepping in a mudhole and end up drowning.

“Oite kebori” was one of the tales that appeared in the “seven mysterious tales of Honjō”. Others included “Kataba no Ashi” (or “The Single Root”), “Tanuki Bayashi” (the “Badger Dance”), “Ochibanaki Shii” (the “Evergreen Beech Tree”), “Okuri Chōchin” (or “the Fleeting Lamp”), “Tsugaruke no Taiko” (the “Drum of the Tsugaru”), and “Mutō Soba” (the “unlit soba noodles”), among others.

“The Fleeting Lamp” was a somewhat positive tale. When hurriedly returning home late at night, a lamp would occasionally appear and disappear off in the distance ahead of the person running. This lamp was held by a beautiful woman. However the top half of the woman might be hidden by the dark of night, so it was by no means guaranteed that the woman would be beautiful.

“The Single Root”, by way of contrast, was apparently a true tale of a tree root whose leaves would only appear on one side.

“The Evergreen Beech Tree” was a tale of a giant beech tree whose leaves never fell off, and other such tales of woe.

Then there was “Ashiarai Yashiki” (or “The Foot-Washing House”). According to this tale, in the dead of night a giant foot, dripping with mud, would suddenly appear from the ceiling. If you washed the foot, it would immediately disappear. However if you left it be, it would grow violent and impossible to control.

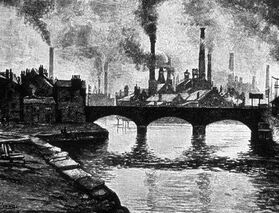

In addition to Honjō, many other monsters appeared in the newly built suburbs of Azabu and Yoshiwara close to the outskirts of Edo. As the city continued to develop, the population increased, and many of the suburbs that were rapidly emerging contributed to the destruction of the natural environment surrounding them. The foxes and badgers that lived in such areas found themselves without places to live nor food to eat, and so began to appear more frequently in human habitats. It was among such conditions as this that tales of creatures undergoing transformation grew in popularity.

For the people of Edo, who loved a good mystery, the very height of this culture was manifest in the works of the scholar Hirata Atsutane (平田篤胤). He would go about collecting tales told by the people of the city, and would note them down for posterity. Among these tales was one of “Heitarō”, the boy who feared nothing. In this tale, despite being visited by a number of different monsters and creatures over many nights, Heitarō was afraid of none of them, merely commenting “well that’s an odd looking thing”. Such was his reaction to them that many of the monsters grew more fascinated with him, with ‘Oyadama’ (a giant eye ball) eventually deciding to become his guardian spirit.

Atsutane conceived of a world in which gods, spirits, and humans all co-existed. He opened up a private academy in the centre of town known as “Ibuki no Ya” (or ‘The Breathing Inn’), where he told tales of other worlds to those who would listen. He reportedly had 553 students of his own, and when combined with visitors these might exceed 3000, making it a very lively venue indeed. Such was his fame that Atsutane came to the attention of the Bakufu government, who ordered him on three separate occasions to “quit talking such nonsense, and advance the cause of national studies.”

While tales of terror were certainly used as entertainment before the Edo period, in the early Edo period virtually all ghost stories were about men. There were tales of spirits who, after being defeated in battle, would continue to haunt their descendants. There were violent ghosts, who after being killed in a fight with another warrior, laid a curse on their murderer’s children, saying that he would “kill them all”. It was only from the mid-Edo period, a time of relative peace, when people started to think that it was far more frightening to have a beautiful woman transform into a monster.

The person most responsible for the popularity of this type of narrative was the Rakugo entertainer Hayashiya Shōzō (林家正蔵). He believed that rather than simply trying to frighten people, using humour and other elements would make stories more memorable. So he would use various props, such as flying fireballs or modified pieces of furniture. People dressed as ghosts would also suddenly spring out behind an audience listening to one of Shōzō’s stories and frighten the bejesus out of them. Over time, tales of terror became popular within the world of Kabuki theatre as well.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed