Source: pinterest.com

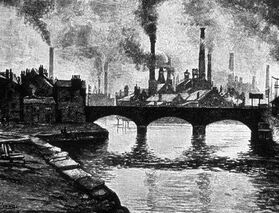

Source: pinterest.com The nineteenth century, carrying on the ethos of the industrial revolution as it was practiced in the United Kingdom from the eighteenth century onwards, regarded nature as a thing to be tamed, codified, and exploited for the betterment of the nation and for humanity as a whole. This was to be achieved by a naked form of capitalism, of exploitation for the sake of profit, with the means of production and distribution to be ever thus refined and improved so that those profits could be distributed faster and wider than before.

To realise this goal, the United Kingdom (and then other European states) needed to control resources and subjugate those who held them so that both could then be put to use for the sake of the industrial state. Hence the development of imperialism, and with it militarism, which would in time be followed by mercantilism and commercialism. It created the basis for the concepts of destiny and superiority that were central to nineteenth century theories concerning race. These forces would continue to hold sway over Europe, and its colonial branches, for over a century as the drive to achieve “prosperity” sent government and commercial entities to every corner of the globe in the search for more resources to exploit.

Such ideology, which believed in eternal progress and industrialization as the key to “prosperity”, only occasionally considered the ramifications of what such activity would do to the natural world. Adjustments would not begin to be made until the effects of industrialisation and commercialisation became blatant to large sections of society, thus initiating movements (from the late 1960s onwards) aimed at trying to mitigate some of the damage created over the previous century. Yet the fundamental ideology underpinning the industralisation and commericalisation of Western and later Eastern societies – exploitation of resources for the scientific betterment of society and humanity as a whole – did not change. It continued to hold sway over government and business thinking, and dictated how such bodies would react to changes in the natural world.

Those forces that the nineteenth century thought admirable and aspirational have, over time, proven a curse to the modern world. This naked desire for “prosperity” has ruined the very ecological systems that allowed human society to thrive in the first place. If human society is to have a future, it must learn that “sustainability” is crucial not only to humans but to all forms of life. “Sustainability” means rejecting those forms of industralisation which cause the greatest harm to the largest number of species. It, at its very core, means finding ways to live which do not damage the threads by which life itself is sustained.

Humans have within their means the ability to change their society to make it sustainable. It means moving away from the destructive technology of the nineteenth (and, to a great extent the twentieth) century and the exploitative ideology that drove such destruction. Yet the time for change is running out before irreparable harm is done that will diminish humanity and condemn it to a future plagued by nightmares.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed