Source: The Japan Times

Source: The Japan Times As has been reported elsewhere, the main sticking point for the RAA was Japan’s use of the death penalty. As one of the few OECD countries that still practices capital punishment, successive Japanese governments have maintained that the death penalty serves as a deterrent and a means of adequately conveying the outrage of society against those who commit the most heinous of crimes. There is a social expectation that the death penalty remain an option in response to murder etc., which is at odds with legal scholarship and social mores in Western nations (bar the US) where concern over the limit of state power to execute citizens and the rights of the individual and human dignity have received greater emphasis.

The possibility of ADF personnel being subject to capital punishment proceedings in Japanese courts obviously didn’t sit well with Australia’s bureaucratic and political class, particularly given the fact that within most of the defence agreements that Australia has with nations that still practice the death penalty (the UAE, Malaysia, PNG etc.,), a clause exists that exempts or grants immunity to ADF personnel from the death penalty in the host nation. Yet such is the central role played by the death penalty in the Japanese legal system that exempting visiting foreign military forces from it would be both legally and politically impossible.

In the background to this dilemma lies the long-standing US-Japan Status of Armed Forces in Japan Agreement, specifically Article XVII, which allows US servicemen and women to be tried exclusively by US courts (i.e., “those subject to the military law of the United States”, itself a sticking point given numerous incidents involving US military personnel in Japan over the decades), but which offers no exemptions from either the US or Japanese authorities’ use of capital punishment.

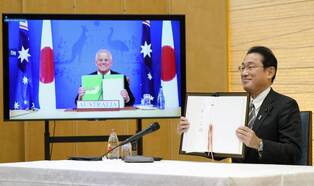

Such was the sensitivity of this issue that following the ‘in-principle agreement’ reached by PM Morrison and then PM Suga during Morrison’s visit to Tokyo in November of 2020, no mention was made of how the issue of the death penalty would be addressed in the RAA. So the issue continued to be thrashed out behind closed doors as each side sought to convince the other of its concerns and what degree of compromise could be reached. Apparently the RAA now agrees to have a “case-by-case” consultation process for any crimes that might warrant the death penalty in Japan.

With the Agreement now signed, the next step along the road to ratification is its review by parliamentary committees in both countries. While questions will most likely be raised about to what degree ADF and SDF personnel will be subject to the domestic laws of either country (and on what basis “case-by-case” decisions will be made), apart from some objections from long-standing opponents to security agreements, the core articles of the Agreement should receive approval and be entered into force at some point this year.

Another interesting development stemming from the RAA has been the decision to update the 2007 Joint Security Declaration. This is, according to newspaper reports, an inevitable result of the deteriorating security situation in the Indo-Pacific region and the need for both nations to engage in greater levels of intelligence sharing. While not as visually appealing as the RAA (i.e., large numbers of SDF personnel and equipment present in Australia), an upgraded Security Declaration might have even further reaching consequences for security relations between Australia and Japan. While some have advocated for both nations to essentially go all in and declare an alliance, the upgraded Security Declaration will influence the degree of cooperation between both sides to the point at which it will be an alliance in all but name.

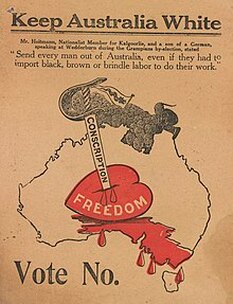

No doubt reservations will be raised among some members the Australian cognoscente that Australia is committing itself to a defence relationship that might increase the risk of becoming entangled in a dispute within the East China Sea. Yet Australia is already committed to that region, and has a major interest in contributing to efforts to try and preserve the existing order and ensure a continuation of democratic principles and the rule of law. To abrogate that responsibility and dismiss the concerns of regional partners as ‘nothing to do with us’ would condemn Australia in the eyes of nations seeking reassurance that they are not alone in the face of the rise of a belligerent, nationalistic dictatorship bent on establishing a regional hegemony. It would, in fact, heighten rather than diminish tension and expedite the already increased militarisation of the region in an ‘every man for himself’ rush to be armed to the teeth born of mistrust.

It is better, therefore, for us to act in union with partners who share our concerns and who are willing to transcend their reservations to achieve a mutually held goal – the maintenance of stability through cooperative deterrence. Japan and Australia have shown the way forward, and the ripple effect from this will continue to echo in the capitals across the region and further afield for many years to come.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed