Source: International Research Center for Japanese Studies

Source: International Research Center for Japanese Studies Starting with the closing years of the Edo period, Siniawer outlines how younger, and often poorer, members of the jizamurai class provided their muscle in support of the restoration of and resistance to Imperial rule (i.e., think the Shinsengumi, along with the Imperial supporters from Satsuma and Chōshū). It then details how these protagonists eventually faded away, to be replaced by a different sort of political activist - one that initially acted on behalf of individual patrons (often providing personal protection services to politicians against their political enemies), but which in time joined groups that supported political parties, fought against rival gangs (from both the left and right wing of the political spectrum) and contributed to the spread of Japanese imperialism.

Although the book does not include any breakdown of the number of incidents of political violence per year, which would be useful to determine if during the course of a century there was a remarkable upswing in violence for political purposes, it illustrates in vivid detail many of the more famous incidents of mayhem that punctuated political life during the nascent years of Japanese parliamentary democracy, and how political violence transformed from an instrument of democratic expression to a tool of imperialism and the rise of the fascist state.

It does seem, from the evidence provided, that to enter politics during the period of 1870 – 1930 was to take your life in your hands, and that serious injury or death could result from an inopportune meeting with ‘ruffians’ supporting your rivals or who simply took a disliking to you and whatever political platform you espoused.

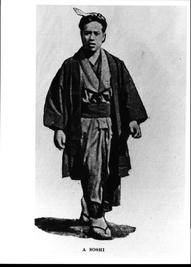

What makes this book even more remarkable is the amount of detail it provides about the protagonists of this violence. While I am aware of Japan’s violent political past (and present, if the activities of Diet MPs during debate on the Abe cabinet secrecy laws are any indication), I was not sure of the extent to which it was applied and who practiced it. Ruffians provides that background and more, down to details on the type of clothing worn by these practitioners of political violence.

Siniawer also makes the important point that political violence was not unique to Japan, and that similar incidents of groups of young men using their physical strength to impose their views on others was a feature in US and UK politics during the same period. What is interesting is the way in which political violence was encouraged in Japan, and how it became so entwined with the public conscience regarding political action that it would distort and undermine the very democracy that had allowed that conscience to emerge in the first place.

It is an excellent resource for those seeking to understand how political ideals were strongly contested in Japan during the century following the Meiji Restoration, and I can’t recommend it highly enough.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed