Source: jp.wikipedia.com

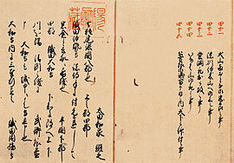

Source: jp.wikipedia.com These military exploits make the following letter that Yoshihiro sent to his wife, Saishō, all the more interesting, as they reveal a side of warriors in the Sengoku era that are rarely given prominence – that is, their concern for others, and their capacity for tenderness. The letter itself was written on the 19th day of the 3rd month of Tenshō 19 (or 1591), when Yoshihiro was fifty seven years old. While Saishō’s exact age is unknown, she was of comparable age to Yoshihiro, and so it is quite touching that although many years had passed, the affection that Yoshihiro felt towards his wife did not diminish but grew stronger (154);

“Your letter dated for the 26th of the latter half of the first month has only just arrived. I am relieved to know that nothing untoward appears to have happened where you are either.

As I have said previously, recently the grey hairs on my head have increased so that it looks as though snow has piled upon it, wrinkles have formed deep crevices on my face that look like a series of rolling waves, and when I look at my face in a mirror in the morning, I find it hard to do so even though it is my face. Were I to meet you, you would be quite surprised at my appearance and how much I have aged. I look like a completely different person.

It is often said that the rapidity by which time passes is difficult to bear, yet I wait for the time when I may take the road home. Time really does move slowly, damn it.

Mataichirō (Shimazu Hisayasu) occasionally visits you, doesn’t he? I’d like to know details about this.

It is essential that Matahachirō (Shimazu Tadatsune, later Iehisa) be encouraged to perform his public duties.

Are Chōman (Shimazu Tadakiyo) and Go Ryō Nin (the youngest daughter in the Shimazu household) both behaving themselves?

At any rate Go Ryō Nin is unique, isn’t she? (having been born when Saishō was comparatively old by early modern standards)

It is right that we do not refrain from giving thanks to the gods and Buddha for all things.

In order to ensure that Ōshinoji (possibly the child of Taishinsai and Shimazu Tadachika’s son Tomohisa), Sanmi (possibly the child of Sanmi Nyūdō and Itō Yoshisuke’s son, Suketaka) Toyama Fūfu (the daughter of Toyama Ōkurabō and Niiro Tadatomo), Tōgō Oba (possibly the wet nurse to Tōgō Shigetora) and other women of the household to not neglect their duties, I want you to listen to what they say, and gather useful information about them.

3rd month, 19th day

Yoshihiro

To Lady Saishō

(P.S: I saw you in my dreams again tonight. To think that we would meet here….

If you happen to have any good news, no matter how many times you’ve told it, I’d be happy if you could write it down for me.

Could you also ask Matahachirō to practice his prose and other studies?

I hope that Chōman has already started his education. I think it would be good to ask Lord Monseki (Shōrenin Monseki Sonchō Hōshinnō) to lend some textbooks to Chōman.

I’ve heard that Mataichirō is getting along well with his wife. I would be overjoyed if, by the light of the moon and stars, the relationship is subsequently blessed. As for advice, I’d be grateful if you could choose the right time to speak to the couple about this.

Also, please tell my elder brother Yoshihisa in Kagoshima and my daughter Oyachi in Hiramatsu that all is well with me.

Best wishes to you in all things). (156-157)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed