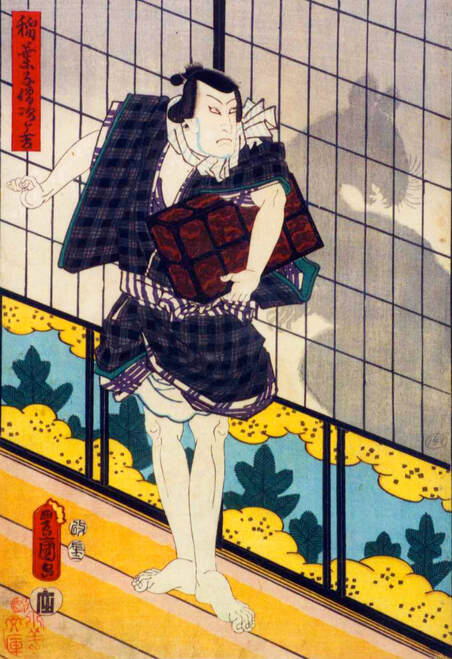

Benten Kozo, by Utagawa Kunisada

Benten Kozo, by Utagawa Kunisada Chapter 12 The dramatic crimes of Nezumi Kozõ (continued)

Apocryphal tales and legends

While it isn’t particularly clever, there is a certain attraction in being generous and having no attachment to money. The ‘Miscellaneous Tales from Bunbõdõ’ spoke of Jirõkichi, who had spent half a year on pilgrimage to Kyoto to visit Konpira Shrine only to return to Edo in order to continue to pursue a life of gambling, in the following manner.

“Regardless of whether he had lost or won at gambling, Jirõkichi would give money to anyone; from those who had lost every stitch of clothing to professional gamblers, and would do so without question. Depending on the person, he might buy someone clothes or treat them to entertainment at Yoshiwara or at the Okabasho (red light districts). The fact he would be so generous while lending money led to him being praised with comments like ‘That’s just like Jirõkichi’, and everyone from cats to ladles (a phrase basically meaning ‘all and sundry’) sang his praises, calling him ‘Taishõ, taishõ!’ (literally meaning ‘general’, but in this sense meaning ‘big man’ or ‘boss’). (242, 244)

The extraordinarily generous Jirõkichi was obviously a vital acquaintance for the many poor residents of Edo. This too was recorded in the ‘Miscellaneous Tales from Bunbõdõ’:

“(Jirõkichi) would lend money to whomever needed it, from the poor, to those afflicted by serious illness and in need of treatment, to those heading out on a pilgrimage to Ise shrine.” (244)

While the money that Jirõkichi gave away might have come from somewhat illicit sources such as burglary and gambling, one can say that Jirõkichi himself had every qualification necessary to be recognised as a true gizoku.

For his part, Matsuura Seizan compiled a variety of sources related to Nezumi Kozõ. They are contained within the eighty-first scroll of the ‘Evening Tales of the First Lunar Cycle’ under the heading ‘Various Stories of Nezumi Kozõ’. I’d like to introduce a few of those to the reader. (244)

When he was being questioned, Jirõkichi admitted that:

“I tried two or three times to break into the household of the lord of Hikone province, the Ii family. (Because they were an illustrious samurai family) both the inner and outer walls (of their household) were high, and I knew it would not be easy to either get into or to steal anything from there.”

He also had the following to say about the Ginza (a place to manufacture coinage, much like a treasury or a mint):

“Even in the dead of night, the security (for that place) was water-tight. In the end I wasn’t able to steal a single thing.” (245)

Yet the Ii household and the Ginza were the exceptions to the rule. By and large the security for samurai households was lax, and someone of the talents of Jirõkichi could easily find a way to break into them. The ‘Various Stories of Nezumi Kozõ’ also contained the following tale:

“When breaking into the house of an important daimyõ family, Jirõkichi would spend around two or three days hidden in the garden of the residence. He would watch the interaction between the daimyõ and his wife, seeing how they offered one another drinking cups and the type of names they called one another. This way he would remember every minor detail about the couple. Apparently the officials listening to this confession later relayed its content to the guards from the residences described by Jirõkichi, and the guards were terribly embarrassed.” (245, 246)

Seizan also felt affinity for the type of attitude Jirõkichi displayed during his interrogation:

“When he was being questioned, Jirõkichi showed no signs of fear, saying “This is divine justice. I scaled the high walls of many samurai household and managed to break in and easily take whatever I wanted. The fact that I am now bound by ropes and been reduced to this state is humiliating. My time has definitely come.” (246)

As an afterward to this paragraph, Seizan added the following “While Nezumi Kozõ was brave, the world has no use for a thief’s bravery.”

Seizan also wrote about how Nezumi Kozõ made efforts to ensure that his relationships with women would not cause them difficulties. In one of these, he wrote:

“(Before he was arrested) Jirõkichi sent these women ‘declarations of separation’ (to prove they were not co-habiting). To those women reduced to living in a nagaya (a boarding house, usually occupied by the poor) after leaving him, he would unfailingly show concern down to the smallest detail for their well-being, often sending gifts to their landlords or ‘pimps’ (for their rent and food etc). He was praised for being a man unparalleled in his combination of both intelligence and sense of honour.” (247)

A similar story was relayed in the ‘‘Miscellaneous Tales from Bunbõdõ’:

“After being captured in the house of Matsudaira Kunaishõ-yû and realizing that he was likely to be executed straight away, Jirõkichi made a request “Don’t kill me here, but take me to the town magistrate and hand me over to him. You can execute me after I’ve explained myself.” (247)

But why would he do this? Jirõkichi then gave his reason. “It seems someone has already committed seppuku (ritual suicide) in order to take the blame for a burglary for which I was responsible. A lot of money was taken so there are probably a lot of suspects. If you take me to the official’s residence I will confess everything and ensure that more people are not punished (for a crime they did not commit).” (247)

So Jirõkichi was duly handed over to the town magistrate, where he confessed in full to both the houses he had broken into and the money he had stolen. Of course, he did not simply confess, but went back over all of the crimes he had committed over a decade. He explained in detail everything about his robberies, from the methods he used to enter houses to the amount of money taken.

This process could not have been easy. In order to jog his memory a bit, Jirõkichi looked at a copy of the Bukan (a ledger which detailed all of the insignia of the various retainer households to the Tokugawa Bakufu, along with the posts they were responsible for administering) and tried to recall in as much detail as possible what he had done in each residence. (248)

Knowing that he would receive the ultimate punishment and that there was no use in trying to amend his ways, and by accepting punishment in order to absolve anyone else who might be under suspicion, Jirõkichi gave us a model of what a gizoku was mean to be. Even when he was being handed over to the authorities, the ‘Miscellaneous Tales from Bunbõdõ’ tells us that he showed no signs of fear or anger, and from the saddle of the horse he was sitting in he began to intone the ‘Lotus Sutra’ (Namu Myõhõ Renge Kyo). (248)

‘I, Nezumi Kozõ, witnessed your performance of Nõ’…

An honourable thief who doesn’t kill, and a man of deep sensitivity. Optimistic, fond of women, fastidious and brave. Nezumi Kozõ Jirõkichi was certainly a ‘rascal’ about whom there is no shortage of legends and apocryphal stories. Yet there is no more fitting tale of Nezumi Kozõ and why he became the archetype for theatrical depictions of criminals than that contained within the forty-ninth scroll of the ‘Evening Tales of the First Lunar Cycle’, a story titled “Nezumi Kozõ watches a performance of Nõ theatre”. (249)

According to this story, the widow of the former lord of a subsidiary of Himeji in Harima province began talking to a young Buddhist nun one day, and that nun later went on to recall details of the conversation to Matsuura Seizan. One of those details was as follows:

“A performance of Nõ theatre was to be held in the residence of a certain lord located next door to that of the lord of Himeji, Sakai Uta no Kami (obviously, because he had been the unfortunate victim of a burglary, the name of this other lord was not revealed). The owner of the theatre in which the performance was to be made(i.e., the other lord) noticed a man standing in the centre of the space used by the performers in-between acts. The man looked to be around 18 or 19 years old, and his half-moon haircut (the haircut most common to men during the Edo period, whereby all of the hair on top of the head was shaved off, leaving just the hair around the sides and back. This apparently kept the head cooler when wearing a helmet) was long and straggly. He was wearing a somewhat audacious half-sleeve jacket, and had a short sword shoved into his waistband.

The lord spoke to the retainers on either side of him, saying “An intruder! Quickly, catch him and throw him out!”. Yet the retainers could see no sign of an intruder. The lord repeated his order, so his retainers made their way up onto the stage and searched about. Yet again, they could find no trace of any intruder.

Only the other lord had seen the man in question. His retainers searched desperately in an attempt to find him, but to no avail.” (249, 250)

The forty-ninth scroll of the ‘Evening Tales of the First Lunar Cycle’ was written in Bunsei 7 (1824), when Jirõkichi was 28 years old. The fact that the other lord said he had seen a youth of 18 or 19 suggests that Jirõkichi had a young appearance and was also somewhat short in stature. The eighty-first scroll of the ‘Evening Tales of the First Lunar Cycle’ includes a depiction of Jirõkichi’s appearance after he had been executed and his head put on display. “Apart from some light scarring caused by smallpox, his skin was pale, and he did not have the look of a criminal, but possessed the placid, gentle expression of an ordinary tradesman.”

So Jirõkichi did not look like a criminal. But that doesn’t mean it wasn’t surprising to the other lord to see a man standing on a stage in a room within his own residence. The fact that his retainers couldn’t also see the man probably had less to do with the man being a fabrication of the other lord’s imagination and more to do with the fact that Jirõkichi could make himself scarce very quickly. (250)

The widow’s tale continued.

“The man may have fled into the residence next door (that belonging to the lord of Himeji). This was certainly the conclusion reached within the other lord’s household, and so word was sent to the Sakai household to be on the alert for an intruder and to catch him if they saw him. Guards from the Sakai household were placed in the gap between both households, yet the intruder did not appear.”

The highlight of this tale comes next. According to the original source “Thereafter a piece of paper was discovered on the stage in the theatre. On it was written “I, Nezumi Kozõ, saw your Nõ performance”. The theatre people were unable to hide their excitement, exclaiming “Ah, that man was the famous Nezumi Kozõ!”. It was like a scene from a period drama (in fact, this very scene may have been recreated in a movie). (251)

The widow who was relaying this story to the nun is believed to have been the wife of Sakai Tadasada (lord of Niita Himeji), who died in Bunka 13 (1816) at the age of 37. To what extent the above story is true we cannot tell, but the source of the story was an actual woman who lived during the time in question, and who was living in retirement in a separate abode belonging to the same household. (251)

So who was the other lord referred to in the story? At the time, the households that neighboured that of Sakai Uta no Kami was the castle (Edo castle) to the west, while to the north were the Hitotsubashi, one of the three main houses of the Tokugawa family. The head of that household at the time was Tokugawa Narinori. To the east lay the households of Ogasawara Daizen Daiyû Tadakata (lord of Kokura in Buzen province) and Mizuno Dewa no Kami Tadanari (lord of Numazu in Suruga province). (252)

When we narrow down the candidates to the three remaining households (i.e., excluding Edo castle), we find that the reference within the ‘Evening Tales of the First Lunar Cycle’ that describes the household of this other lord uses the term ‘yagata’. It is my belief that the victim in question was none other than Tokugawa Narinori of the Hitotsubashi.

As to why I think this, I can point to Jirõkichi’s own confession. The households of the other daimyõ are referred to in the confession using the term ‘yashiki’, whereas that for the three principle households of the Tokugawa family and their rulers is “O-yagata”. At the time of the incident, Tokugawa Narinori was 22 years old, whereas Ogasawara Tadakata was 55 years old and Mizuno Tadanari was 63 years old. It seems most likely, given the manner in which Nezumi Kozõ was only seen within the blink of an eye, that the youth Narinori stood the best chance of having seen him. (252)

Short and handsome

So what did Jirõkichi look like?

The short-story author and playwright Hasegawa Shigure (1879 – 1941) was foremost in creating the image of Nezumi Kozõ as a man of short stature. According to Hasegawa, it was his grandmother who first described Nezumi Kozõ to him. In his ‘Old Tales of Nihonbashi’ (Kyûbun Nihonbashi), Hasegawa echoed his grandmother’s words, writing “He was short, with some slight pockmarks (on his face), quite a tiny man.” (253)

Hence one reason that Jirõkichi was referred to as ‘Kozõ’ (literally ‘little monk’, but also carrying the meaning of ‘shorty’ or ‘kid’) was because he was short. This becomes more obvious when one looks at the character of Heikichi, who appears in the human drama ‘Midori no Hayashi Kado no Matsutake’ (The Pine and Bamboo Gate of the Green Forest) by San’yûtei Enchõ. (253)

Heikichi is the boss of a gang of pickpockets, and 27 years old. About himself, he says “While I am little, I certainly don’t starve.” Another character who idolizes Heikichi, who goes by the name ‘Oseki’, voices his concerns about Heikichi when preparing to hand him 100 ryõ that Heikichi needs, saying “I’m worried that this (money) will make the short-statured Heikichi bigger (meaning more prominent)”. (253)

So Enchõ may have based his character Heikichi on the historical image of Nezumi Kozõ. But that’s not all. At that point in time, the name ‘kozõ’ carried connotations of being either a small thief or pickpocket. For example, the character ‘Benten Kozõ’, who first appeared in a performance at the Ichimura-za (Ichimura theatre) of Kawatake Mokuami’s ‘Aoto Zõshi Hana no Nishiki-e’ (A Portrait of Red Flowers and Blue-millstone Paper) in Bunkyû 2 (1862) is a short but handsome young man. (253)

The female guards attending the young princess in the story all remark on his appearance, saying that he is ‘a good looking man’ and swoon over him. For his part, the 17 year old Benten Kozõ says of himself “I have a small frame.” (254)

*It also seems as though there was another person who went by the name of Nezumi Kozõ before the arrival of the historical figure best recognised for having that name. He was neither a thief nor a pickpocket, and was in every way a ‘Nezumi’ (rodent). He was small, sly, and wicked, and so was called that name out of spite. (254)

Jirõkichi – a performer right up to the very end

On the day of his execution, Jirõkichi appears to have discovered the ‘actor’ in him. According to the ‘Miscellaneous Tales from Bunbõdõ’, Jirõkichi was wearing the following clothes when he was handed over to the town magistrate:

“He had a dark blue, rough-hewn long shirt on, underneath which he wore a white, shorter sleeved shirt. He had an eight-layer waistband around his middle, and wore both fingerless gloves and gaiters which had been dyed white.” While this means little to those unfamiliar with the style of Japanese dress at the time (myself included), it was apparently typical wear for someone of a short stature. After being bound and placed on a horse, Jirõkichi proceeded to close his eyes and start solemnly reciting the ‘Lotus Sutra’, as explained earlier. (254)

It goes without saying that crowds thronged to the roadside to see Jirõkichi pass. Of particular interest was the comment in the ‘Miscellaneous Tales from Bunbõdõ’ which said that “People were openly weeping, and drying their eyes on their sleeves.” Jirõkichi, it must be remembered, had limited himself to breaking into the houses of wealthy samurai and hadn’t killed or injured anyone. Any money that he took he used on gambling or entertainment, and so contributed to the economic well-being of the townspeople. So as far as they were concerned, his were victimless crimes. And so they wept as they watched him head off to his execution.

Of course, they may also have been doing this because of Jirõkichi’s talents as a performer and his ability to make an audience cry.

Nezumi Kozõ wasn’t the only figure from history recorded to have moved an audience to tears while facing his demise. In the ‘Records of Interrogations by Edo Magistrates’ by Sakuma Masahiro, there lies the tale of one ‘Kawachi Mushuku Sadazõ’. Sadazõ was a true villain, originally sentenced to exile on an island, but who escaped to continue a series of murders and armed robberies. After being captured, he, and six of his accomplices, were sentenced to die at the Kozuka-tsubara execution ground by crucifixion. (255)

On the way to the execution ground, the prisoners asked that they be provided with some food and drink. Their overseer (the official tasked with witnessing the execution) decided to allow this to happen and paid for some refreshments using his own money. Yet Sadazõ refused to accept any of it, and rebuked his accomplices saying “It doesn’t matter how much you eat or drink, it’ll all come running out of you soon enough. It’s pathetic, so stop it.” Sadazõ had two half coins hidden in his mouth which he then proceeded to spit at the beggars in the crowd of onlookers. He then continued on his way to the execution ground. (256)

Sadazõ was tied to his crucifixion pole, and in front of him his executioners, both on the left and right, made their preparations to stab him with their spears. I’ll let Sakuma Masahiro finish this tale in his own words:

“(Sadazõ) said to his executioners with a smile “make sure to stick me properly”. Even after being run through by one spear, he turned to his accomplices next to him, happily urging them to “take it like you mean it”. In the end, all seven of them, with neither fear, nor pain, nor panic written on their faces, met their end, being stabbed a total of 12 or 13 times.” (256)

And so a gang of villains met a ‘befitting’ end, although this example was quite clearly a rare exception. What Sakuma was trying to convey to the reader was that ordinarily, upon hearing their sentence of death, most prisoners would lose all of their stoicism and panic and rave. The more cowardly among them would turn a corpse-like pallid white, and would lose all the strength in their legs and collapse in a heap. (256, 257)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed