Source: Kotobank. Voyage Marketing

Source: Kotobank. Voyage Marketing Introduction – Was ikki (translators note: a revolt or uprising) an anti-establishment movement?

Towards an age of uncertainty ‘post 3.11’

The unprecedented disaster that struck Japan in 2011 proved to be an opportunity for us to reconnect with the long-forgotten value of relationships. Words such as ‘relationships’ and ‘bonds’ were used with such frequency following the disaster that issues that until recently had occupied society, such as people dying alone and the ‘disconnected society’, seemed like they had been concocted out of thin air (of course, all that had happened is that reporting about the issues had decreased, not that they had actually improved). These words continue to be put to good use. (13)

When your average person hears words like ‘relationships’ and ‘bonds’, the first thing that probably comes to mind are relations with family. Immediately after the disaster, there were many people who sought out family members, desperate to know whether they were safe and using every means imaginable to get in contact with them. Among my friends, some took their parents in to live with them after their family home was swept away by the tsunami. And post-disaster, the number of people who decided to tie their nuptials increased, leading to the term ‘disaster wedding’ (shinsai kon). (14)

In addition, households in which three generations live under one roof (an aspect of which contains strong expectations regarding economic and child-rearing support), which had (according to 2010 statistics) fallen to just 7% of all households, started to show signs of a recovery, particularly in cities. Of course, in modern society, where the make-up of the family continues to diversify, it would be difficult from a practical point of view to bring about a revival of large families. For people who have left their home town to move to the city, if they then decide to live with their parents, they either have to bring their parents to the city or they have to give up their job in order to return to their hometown. And then there are housewives who don’t need to hear that “no matter how violent your husband is, you mustn’t divorce him, if only for the sake of the children”. (14)

While there has been a boom in recent years in nostalgia for the Shõwa era, specifically ‘the Shõwa era in which a family, although poor, leaned on one another and happily lived together’ (which contains a considerable amount of romanticisation), you can’t turn back the clock, and there are limits to the safety net of relying on relations with family members.(14)

In fact, one of the largest problems that modern society faces are those people who have slipped through the cracks of the pre-existing arrangement between families and businesses and who find it difficult to cope. Given that the Japanese taxation and social welfare systems were created for the ‘husband works full time as a company employee, wife remains at home with two kids’ model - in other words ‘the happily married couple’ - those who fall outside of this model, such as households where both parents work, or where there is only one parent or where a parent is a temporary labourer, experience great social disadvantage. (14-15) And knowing what might befall them should they happen to slip up, there has been a trend in couples who fear any issues that might arise between them and so allow their relationship to atrophy (in the case of company employees, they might throw away any of their own ambitions or ideas and become entirely subservient to the company, so much so that they apparently live on company grounds).(15)

With non-permanent employment on the rise in today’s society, anyone who lives as a ‘full time housewife’ or ‘full time employee’ might be regarded as a ‘winner’. Yet given that this means that you must hang on for dear life no matter how dreadful either a family situation or workplace happens to be, these ‘winners’ are actually in a ‘prison’ where happiness is in limited supply (while the Japanese economy was growing, these problems remained hidden beneath the surface). (15).

The new ‘medieval era’ present in modern society

Some of the more elderly ‘intellectuals’ in Japan may have forgotten that in Japan’s post-war democracy, ties of ‘blood’ and ties to ‘land’ were regarded in a negative light. Recently a young essayist by the name of Furuichi Noritoshi made an astonishing literary debut by pointing out that these ties proved an impediment to the development of the ‘modern individual’ and criticised them as antiquated ‘restraints’. (15)

In my specialist field of medieval Japanese studies (particularly the research conducted by Katsumata Shizuo and Amino Yoshihiko), ‘unrelated’ (muen, or ‘without ties’) as a concept carries a positive meaning (as discussed later) and is not distinct to the development of the modern intellectual and his or her progressive ideas. (16) Indeed, I do think that it is quite indulgent for people to say “the best course of action is for family members to rely on one another” when disaster strikes.

Following the Great East Japan Earthquake, many young people made a beeline from across the country to the disaster zone to serve as volunteers. According to Furuichi, the earliest responders to the disaster and those who took a leading role in their volunteer work were members of foreign volunteer organisations who had experience delivering aid to developing countries such as Cambodia and Bangladesh. (16)

While claiming that “Japan is one”, for these volunteers, ‘the Great East Japan Earthquake’ and ‘Cambodia’ were inter-changeable as events that required their assistance. Their motivation for taking the lead in heading for the disaster area was not a result of nationalism emanating from an idea that ‘we’re all Japanese’. Rather it was because they felt sympathy for ‘others’. (16) Now while it might seem a bit cold-hearted to refer to the people of the Tohoku region as ‘others’, consider how tolerable were people who, even though they weren’t directly affected by the disaster, self-indulgently pontificated with a know-it-all expression about their ‘belief in the strength of Japan’ and ‘how Japan will definitely recover’? Rather than relying on an overly sentimental identification with ‘Japan’, it is only by squarely confronting the cold reality of the very different circumstances that these people are under compared to those people in the disaster zone can new bonds be formed and true recovery assistance commence. (16-17)

Together with the march of globalisation, modern society, in which modern order as defined by the sovereign state is becoming increasingly relative, is gradually being referred to as a ‘new medieval era’. Indeed, the idea of overcoming adversity through the creation of new networks rather than relying on the return of communal organisations is the same idea behind the ikki of the medieval period. (17)

The post-war historical view of ‘Ikki’

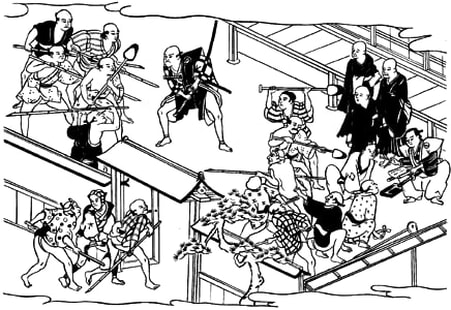

And yet ‘ikki’ has an almost inseparable association with revolutionary imagery. When a continuous series of revolutions occurred throughout the Arab world from 2010 to 2011 (afterwards referred to as the ‘Arab Spring’), something that caught my eye were comments on the internet saying “they are like the ‘ikki’ found in Japanese history”, thereby revealing an association of anti-government people’s movements with ‘ikki’. (17)

In 1917, women from a coastal town in Toyama Prefecture led protests against the monopolisation of rice by local rice merchants and land owners and the unreasonable price at which rice was being sold. This event, subsequently known as the ‘rice riot’ (kome sõdõ) was referred to by papers at the time as the ‘Etchû(translator’s note: former name for Toyama) women’s ikki’. The security protests that took place in the 1960s were also regarded as ikki. (17). The Nobel literature prize awardee Oe Kenzaburõ, in his novel titled “The Silent Cry” (published in 1967) combined the peasant ikki of 1860 (the first year of Manen) with the protest over the security treaty in 1960 (Shõwa 35). (18)

This problem is not merely confined to how the general population regards the phenomenon of ikki. Even specialists in Japanese history more or less treat ‘ikki’ as revolutionary movements. All 5 volumes of the series ‘Ikki’ published by the University of Tokyo in 1961, and which still serve as the foundation for most studies on ikki, describe ikki in their preamble as a ‘fixed form of pre-modern class struggle’.

Class struggle is one of the key concepts of communism. Simply put, it envisages that in a society made up of classes, the non-ruling class will struggle against the ruling class in order to prevent being exploited. In more modern parlance, you might say that it is an anti-establishment, anti-ruling power resistance movement. In its most extreme form, the non-ruling class refuses to abide by the system established by the ruling class and overturns it in a ‘revolution’. The ‘Communist Manifesto’ published by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in 1848 declared that “all history is the history of class struggle”. Class struggle thus occurs over and over again, and every time it does society is reformed and advances. Once the non-industrialist class ‘the proletariat’ seizes political power (the proletariat revolution), the history of class struggle comes to an end and the communist society becomes a reality. This is the ‘class struggle view of history’ that Marx espoused. (18)

So should we regard the ikki of the Sengoku and Edo periods as examples of ‘class struggle’? It does seem as though the dreams and ambitions of postwar historians were reflected onto ikki. Communism gained popularity in postwar Japan in the period of reflection that followed the age of militarism. In historical study circles, ‘Marxist history’ rose to the fore. These historians regarded communism as the pinnacle of social development and held hopes that a communist revolution might take place in Japan as well. (19)

As a result, the ‘history of the Japanese people’s struggle against authority’ became a major theme in postwar historicism. This trend then led the history of ikki to be studied from the point of view of the ‘history of class struggle’. It’s because these historians thought ‘we’re fighting for the revolution too!’. Despite the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end to the dream of revolution, this historical bent, after undergoing a little bit of revision, continues to this day. (19)

Ikki was ‘a link between people’

As will be detailed in this book, in reality ikki was not a struggle over authority or power. To put it more bluntly, the insistence that the ikki of the pre-modern era were examples of class struggle has not basis in fact and were fantasies concocted by postwar Japanese historians. In other words, it something that they wanted to believe was true. Rather than thinking of them as either violent demonstrations or revolutions, it would be more realistic to consider ikki as one pattern of relationships between people. (19-20)

Moreover, the student and union movements of the 1960s did not burn with high-minded ideological fervor, and the fact that they were festival-like in manner speaks to the popularity of ‘utagoe-kissa’ (or coffee shops where one could sing tunes) at the time. Of course, I’m not saying that the participation of folks who indulged in a bit of fun was in any way pointless or ridiculous. If they wanted to belt out tunes so much the better. What I’m saying is rather than trying to deify only those directly involved in trying to bring about revolution, one should also cast an eye over all of the inter-personal relations that form the basis of a political movement. (20)

When one accepts that ikki was not a ‘class struggle’ but a social network, one ceases to think of ikki as simply “something that happened a long time ago”. The study of ikki thus becomes directly relevant to modern society. This book takes that view as a starting point when considering the role of ikki in Japanese history. What I hope to offer is a new way of examining modern society where relations between people often undergo radical transformation. (20)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed