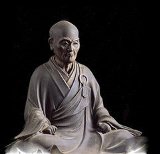

Suzuki Shosan - from elephantjournal.com

Suzuki Shosan - from elephantjournal.com In the 20th volume of the `Taiheiki`, a warrior by the name of Yūki Dōchū makes an appearance, a warrior who couldn`t lift his spirits until he had seen a freshly severed head in front on him every day and who would kill two to three people every day, regardless of gender, and plant their heads in front of him and stare at them. Clearly the warriors of Kii province were not affected by the sickness of serial killing to the same extent as this individual. (pg.14)

In order to better appreciate the lessons espoused by Shōsan, let`s take a look at the original text that admonishes a warrior for killing those in the household lower in status than himself but who won`t kill other warriors. That is as follows:

扨扨比興(さてさてひきょう)千万ナル人哉(かな)、人切ナラハナゼ夫(それ)ヲキリメサレンゾ、他人ノ慮外者(りょがいもの)ハキリエズシテ内ノ者トモノ主(しゅう)トテタツハイ(答拝)シハ(這)ヒ廻ル者トモ少ノコトニ切様ナル比興ナルコトアランヤ。(pg.14)

And so, even if a person is of low social caste and of little consequence, one should not kill them without a specific reason. But if the opponent is a warrior, then it would be foolish not to kill them. (pgs.14-16)

Who ended up a victim of `tsujigiri`?

For Shōsan, who admonished warriors for engaging in `hitokiri` (essentially killing people as an everyday occurrence), for those warriors that engaged in `tsujigiri` (a means of testing the sharpness of one`s sword by cutting passers-by on the road) he had equally harsh words to say. (pg.16)

Shōsan mentions a time when he was `still a part of the secular world` (meaning before he took the tonsure), before the 9th year of Genna (1623), which means it would have been around the time he was still serving in the retinue of the Tokugawa Bakufu as Suzuki Shōsan Shigemitsu. Echū, author of the Roankyō, heard the following story and relayed it in that book (translation follows). (pg.16)

The master (Shōsan) and one of his good acquaintances got to talking about `tsujigiri`. One day they had the following conversation;

Shōsan: You`re lying when you say that you practice tsujigiri. You aren`t capable of doing that.

Warrior: It`s not a lie.

Shōsan: No really, you aren`t capable of tsujigiri.

Warrior: Well then, watch me carry out tsujigiri on someone.

The two of them then went to a remote location and hid themselves. Soon two townspeople approached their position.

Warrior: Right, watch me carry out tsujigiri on these two.

Shōsan: You must not kill these two. You will kill who I tell you to kill.

Soon a very impressive-looking warrior appeared.

Shōsan: Right then, kill that man.

The warrior grew flustered, and stopped Shōsan from stepping out from their hiding place.

Warrior: What, are you mad?

Shōsan: Well, I see now that you are a coward. Even though I told you to kill that man, you couldn`t go ahead with it. Those who back away from such challenges aren`t capable of committing tsugijiri.

Shōsan then went on to say that `if you say that you can`t kill those sorts of warriors, then you had better give up any thought of practising tsujigiri. Killing a townsman using tsujigiri would be the same as killing the god Bikuni or a Boddhisattva.` Shōsan then went on to question whether a person could call themselves a samurai who tried to kill such people in such a way. (pgs.16-17)

These words convinced the warrior of his errors, and he then vowed that he would never again draw his sword in order to carry out tsujigiri. (pg.16)

Questioning the mind sentenced to death

The Roankyō also features the tale of a woman who was saved from execution. This took place at a time when Shōsan was in Osaka in the residence of his younger brother Saburō Kurō (otherwise known as Suzuki Shigenari. According to Kamiya Mitsuo`s `Suzuki Shōsan`, this took place around the 8th year of Kanei (1631), when Shigenari resided in Osaka as a local official). A plot had been uncovered whereby a corrupt official sought to entrap innocent people by accusing them of secretly harbouring fields (thereby depriving the Bakufu of revenue). When the sentence came down that all the male and female members of the official`s household were to be executed. (pgs.16-17)

When Shōsan learned of this, he tried everything within his means to have the women spared. Since the time of Gongen-sama (Ieyasu), no woman had been executed for being associated with such a crime, and so something had to be done to save them. The person in charge of executions in the Kinai region at the time was Kobori Tōtōmi no Kami (otherwise known as Masakazu, and as Fushimi Bugyō served as one of the five principal officials of the Kinai region). When asked, Kobori said that the executions were slated to take place the following day. (pgs.17-18)

Shōsan then went from Osaka all the way to Fushimi, using townspeople to send on a plea for clemency ahead of him. Upon arriving in Fushimi, Shōsan spent the entire night convincing Kobori of the women`s innocence, so much so that come morning a majority of the women had been spared from death.(pg.18) `One must not kill`. This was the message that Shōsan repeated over and over as he sought to gain a lighter punishment for the women.(pg.18) In Shōsan`s own view, `if you can save the life of even a bad person, then there are ways of saving lives, including subjecting them to lesser punishments that no less decrease their suffering`. Also, `no matter how grave the crime, if you continue to execute people again and again this itself becomes a heavy burden.` (pg.18)

Yet this is not to say that Shōsan was advocating to deny the death penalty to criminals, or calling for the abolition of the death penalty in general. If a criminal was crucified, the people who saw that would refrain from engaging in evil acts while the person crucified would regret their actions and this would exterminate the roots of their evil. In such instances executions were also a means of clemency (for to execute someone out of mercy was not itself a crime). (pg.18)

This was extraordinarily realistic. On the other hand, for those people who believed that `executing a criminal was not a crime` and that `you`re not executing the person, you`re executing the crime` and `I don`t execute people. I only execute their crimes`, Shōsan had only words of scorn. In his view, these people were trying to justify executions by couching them in flowery terms. What Shōsan was concerned about was not the justification of executions, but the minds of those carrying out the executions. In his view, even if a person were pitiable, if the law dictated that they had to be executed then this is was what had to occur. Yet those carrying out the executions had always to maintain their sense of mercy. (pgs.18-19)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed