Tokugawa Yoshinobu

Tokugawa Yoshinobu Mitford states that the political situation in Japan underwent a profound change at the beginning of 1867. It was clear that some form of activity was going on in the background as factions competed for influence. The death of Shogun Tokugawa Iemochi on the 29th of August brought things to a head, and the seventh son of the Lord of Mito, Tokugawa Yoshinobu, was appointed to that position through the plotting of ministers from than province. Yoshinobu wasted no time in calling for the combined representatives of foreign lands to an audience with him in Osaka. Mitford states that Osaka at the time was a fairly non-descript town with a myriad of rivers and canals, and had previously been an important focal point of trade. He said that it was referred to as “The Venice of the East”, although in reality there was little to lend credence to that title apart from the abundance of water channels around the town. Mitford wrote that he and Satow were dispatched to Osaka by warship in the first week of February in order to make preparations for the reception ceremony and learn what protocols would be used. Mitford and Satow were accompanied on their journey to the West by a Captain Cardew from the 2/9th Regiment and a Danish Lieutenant by the name of Thalbitzer. They landed at Hyogo, and then made their way to Osaka by horse. In addition to a large number of guards provided for their security, a number of troops were placed at various points along the route. Every time they passed through a check point, these troops would follow behind them, so that by the time they reached their destination they had around 2 or 3 thousand followers. Mitford said that this was ‘good evidence’ of how seriously the government took their safety. When they reached Osaka, they learned that the Emperor Kōmei had passed away on the 3rd of February from smallpox. He had actually died on the 30th of January, yet for some inexplicable reason the date of death had been postponed by four days. Kōmei’s successor, the famous Emperor Mutsuhito (Meiji), was but a youth of fifteen at the time.

Those who knew the young Emperor had deep trust in his abilities, and predicted that an appropriate education and training would result in a person of extraordinary ability, and in that they were absolutely correct. Mitford was convinced that if the Emperor Kōmei had lived, given he was avidly opposed to any interaction with foreigners, the events of the next couple of months would have been completely different.

When they arrived in Osaka, they lodged at a small but comfortable temple located on the Teramachi way. There they were welcomed and were treated with deference, which made their task easier as their every want and need was met. They also became something of a curiosity, and so the roads around their lodgings were packed with spectators, to the extent that they had trouble passing along the streets. Most of the major merchants in Osaka set up stalls in the roads around the temple and proceeded to sell fruit, confectionary, and cheap knickknacks, and Mitford noted that travelers in the early 20th century found this hard to believe.

Mitford admitted that the principal reason for the visit to Osaka was ostensibly to participate in an audience with the Shogun together with other foreign representatives, however Ambassador Parkes also believed it was a fantastic opportunity to gather information about the political situation in Kyoto. He says that this trip was where he first met many of those leaders of various provinces who in the future would play such a large role in the formation of the modern Japanese state.

Mitford mentioned that most Bakufu supporters in Kyoto were from Mito province, and were prepared to sacrifice themselves on behalf of the Shōgun. Their opponents were messengers from Satsuma, Chōshū, Tosa, and Uwajima, all of whom were resolved to bring about the removal of the shōgunate. Mitford says that the English delegation was kept well informed of plot activity in Kyoto, although most of those who passed information to them had, by the time the memoirs were written, died. While in Osaka, he met almost daily with Komatsu Tatewaki from Satsuma, Lord Ito from Chōshū, and the most impressive of the bunch, Goto Shōjiro from Tosa province. Each one of these men and others would play pivotal roles in the formation of the Meiji state. Mitford also says that he and others in the delegation had to take every precaution when they went to meet with these men. They would be accompanied by troops who were there ‘for their protection’. However the delegates managed to slip their guards and meet with province representatives on their own (this occurred at least twice).

Mitford said that one of the consequences of these meetings would have a profound effect on what would later occur in Japan’s history. He said that the goal of the Lord of Satsuma, along with other daimyo, was not to overthrow the shōgunate but to prevent the misuse of its authority. Satsuma wanted to restore the imperial household to its former glory, as it would contribute to stabilizing the nation. As such, Satsuma’s purpose was not to incite a revolution against the Shogun but to act for the benefit of the nation. The Lord of Satsuma had suggested that should the British ambassador come to Osaka and propose a new treaty directly with the Emperor, all of the daimyo would support the proposal. In order to realise this plan, it would be necessary for everyone to gather in Kyoto. Hence if the ambassador lent the daimyo just a fraction of his authority, the daimyo would take responsibility for everything that happened thereafter. It was an audacious plan, and if it had occurred just a few months later, it would have been subject to ridicule.

Mitford writes that while he was in Osaka he and others in the delegation took the opportunity to go shopping, and that he planned to purchase some famous goods and return with them to Yokohama. He mentions that lacquerware was popular, along with pipes of various shapes and sizes, fans, and textiles, all of which were difficult to resist purchasing. He says that wherever he and the other delegates walked, they would be followed by a large crowd. They were accompanied by a minor official with a wakizashi (short sword), who would make a noise like a bird (probably a crow) in order to clear a path for the delegates. However the curiosity of the crowd was too great and they would continue to follow the delegates and wouldn’t be dispersed so easily.

Mitford then says that after returning to Edo from Osaka, a tragedy unfolded at the mission while they were away. He says that many of their acquaintances (presumably among the foreign community) were never able to rid themselves of the fear that they would be attacked by some ‘rogues’ as they wandered along the streets of Edo. Many rogues had become more audacious in their provocations at foreigners, and would often make a display of unsheathing their swords and waiving them around, indicating that they could cut someone in half from their shoulder to their waist. The foreign population in Edo knew of this, and so were taught to shoot to kill anyone who approached them with a sword drawn even an inch out of its scabbard. Mitford writes that the interpreting students (presumably from England) at the mission were also frightened both day and night at the thought of meeting an unfortunate end. They would not venture out from the mission, and even though they were protected in the mission by members of the 9th Regiment and a great many other guards, pleaded with the ambassador to have an Armstrong cannon brought out from Britain and placed at the gate of the mission for its protection.

One evening, one of these youths could no longer handle the strain. After having dinner with some of his friends, he returned to his room, from which two shots were heard. The first shot had apparently failed to hit its mark because the man was shaking so much, and the bullet from that shot was later found in the ceiling of his room. The second shot, however, proved fatal. Mitford writes that suicide is certainly not a contagious disease, yet in the same week another two such incidents took place in Yokohama. Mitford says that it is difficult for people to understand the type of life he and others had to live during the early days of interaction with Japan, but notes that for four years he kept a loaded pistol on the desk that he used to write at. He also says that he would always have a Spencer revolver in one hand and a bayonet in the other when he returned to his bedroom at night and which would lie close by as he slept. He says the fact that anybody can now walk the streets of Kyoto and Edo (Tokyo) while twirling a cane just like they were walking along Regent Street or Piccadilly is a blessing that owes a debt of gratitude to the law that banned the wearing of swords.

Mitford writes that in May of 1867, Ambassador Parkes and he travelled to Osaka for their first audience with the Shogun. Osaka Castle was, as much as it was in Mitford’s day, and as long as you were looking at it from the outside, a large museum to the feudal age and the crowning glory of the last days of Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Mitford then goes into a bit of historical detail regarding Hideyoshi, and expresses admiration for the way in which its stone walls had been constructed using massive stones piled on top of one another but without using any sort of adhesive. He writes that the castle was surrounded by a moat, and protected on two sides by Yodogawa and Kashiwara-gawa. He noted that the stone walls were over 30 feet long and 20 feet high and were beautiful in their simplicity. He said the castle had been attacked by bow and arrow and firearms, but had withstood them all. He then goes into how Hideyori succeeded Hideyoshi, only to be eventually overthrown by Tokugawa Ieyasu.

Mitford writes that the audience with the Shogun took place within Osaka Castle. It was an event that is likely never to be seen again. The position of Shogun was thereafter abolished and became another part of Japan’s distant past. When Mitford wrote his memoirs, the last Shogun, Yoshinobu, had died some months earlier, and the castle was no longer its former self. He wrote that the outer walls were the same, but the interior palaces had been burned down by Bakufu forces in the aftermath of the battles of Toba and Fushimi. These underlings had returned to the castle after fighting for the Bakufu only to find that their leader had fled to Edo, and so harboured a deep resentment towards the Shogun thereafter.

Mitford writes that this must have caused great angst among the retainers and allies of the Tokugawa household. However Mitford then reminds the reader that history does not follow set patterns, and that relying his own memory meant that he was writing things down as he recalled them, zigging and zagging backwards and forwards in time. He writes that the defeated Shogun returned to Edo safely to the castle of his ancestors. One of his younger retainers, Hori Kuranokami, in order to erase the dishonor to the Shogun’s name, suggested that Yoshinobu commit ritual suicide. In order to prove his sincerity, Hori announced that he would commit ritual suicide first. Yoshinobu’s reaction was unexpected, however. He burst out laughing, saying that such a barbaric practice was outdated. Hori then reluctantly bowed and withdrew to an adjoining room. There he bared his chest down to his abdomen, and proceeded to die ‘like a warrior’ by cutting open his abdomen. Mitford says that Yoshinobu’s error was to assume that the ‘barbaric’ practice of ‘belly cutting’ was outdated. He says that even in the early 20th century, it was used as a way to retain one’s honour.

Mitford says that Saigo Takamori, whom he had known for a long time and was one of the leading figures from Satsuma, had died in such a manner during the rebellion of 1877. He said another hero of the treaty ports area, his long-time friend Nogi Maresuke, had committed suicide two years earlier in 1913. Nogi was deeply affected by the death of his beloved lord Emperor Mutsuhito, and so together with his loyal wife, chose to follow the Emperor into eternity.

Mitford then writes that he and Ambassador Parkes had three audiences with the Shogun. The first meeting was private, and as expected, proved to be the most interesting of the meetings. This was not only because it was a new experience, it was also because it allowed for a free exchange of opinions that would not have otherwise happened in a public ceremony. The Bakufu had a number of high officials who had been dispatched for the occasion, while the British delegation had 17 mounted troopers in splendid uniforms from the London Metropolitan Police Force, along with a squad of troops from the 9th Regiment for protection. They were also protected by a number of Japanese guards. The entire retinue headed by horseback towards the castle. Mitford notes that every Japanese citizen they met along the way, whether of high or low status, got off their horses in deference to the delegation.

The delegation itself did not dismount from their horses until they reached the gates in front of a broad square attached to the inner palace. This building was the same as the outer walls and moats albeit smaller, and had its own moat. They were met by a number of high officials and then taken to a waiting room where they enjoyed tea and light refreshments. Mitford then quotes from a letter he wrote on the 6th of May 1867 which described the audience with the Shogun.

The interior of the castle was much more gorgeous than any Japanese building he had seen up until that point. The walls were covered in gold-leaf, and featured depictions of trees, flowers, and birds all painted in exquisite detail by a painter of the Kanō school. Mats weaved from rush reeds were affixed to right-angled hooks plated in gold, and on these large weavings were laid out decorated in orange, red and black silk, similar to a gypsy’s ribbon. The upper section of the room was decorated in the height of Japanese wood carving technology, of a type comparable to Grinling Gibbons (a 17th century British wood sculptor originally from the Netherlands and considered one of the greatest wood sculptors of his age), generously decorated in gold flake, and set within a deeply carved board. Each of these boards had been carved by a different master, and no two boards were alike. The theme of each of these pictures varied, but were made to emphasize beauty, such as a strutting phoenix, cranes, a softly coloured but gorgeous collection of rhododendrons, bamboo whose leaves were being gently blown by a breeze, and an aged black pine tree. The pillars and sidings in the room were made of unfinished Japanese zelkova, fastened into place using gold plated pegs. The ceiling was divided into square shaped sections, each with its own carvings, and each of these was coloured in a deep gold lacquer. The sections between each square were also lacquered in gold or black.

Mitford says that while the effect was certainly gorgeous, it wasn’t without its faults. That was because after 200 years the sharpness of the pictures had dulled somewhat.

While waiting in the first room, Mitford and the ambassador spent time with high officials doing what most people do to pass the time – talking about the weather. After that they were escorted to the meeting room. This room had been laid out in a Western fashion, with 8 seats arranged around a table. At one end of the table was the chair for the Shogun, an impressive lacquered piece of furniture. They were met in that room by senior and junior retainers of the Shogun, where they received word that he would soon come to meet them. Some high sliding doors that divided up the Japanese room they were in silently slid left and right, and an atmosphere of excited tension filled the room, much like an audience waiting for a piano recital to begin. For one or two seconds the Shogun stood like a statue in the space between the sliding doors, presenting a figure of stiff formality. All of the Japanese in the room knelt in a deep bow, except for the senior and junior retainers who remained standing. They probably did this so as not to create any discrimination between themselves and the delegates and so were excused from the usual formalities.

When the Shogun entered the room, he bowed, and then, to borrow a phrase from Tacitus “in the manner of the barbarians”, shook hands with Ambassador Parkes. All of the delegates, namely Parkes, Lowcock, Satow, and Mitford himself, then sat on one side of the table while the other featured the Shogun and four of his retainers. The Shogun then majestically stood up and enquired about the health of Queen Victoria. Ambassador Parkes himself then stood up and asked about the well-being of the Emperor and then proceeded to discuss a range of practical issues. While speaking with the Shogun in private, Yoshinobu revealed that he knew all about recent events that had occurred following the signing of the Elgin Treaty. He spoke plainly in relation to the ‘disturbances’ that the English delegates had recently experienced, and said that he was aggrieved by the many issues preventing the fulfilment of friendly relations between the people of his nation and the delegates. He also revealed his resolve to improve the existing system of government. Mitford writes that the Shogun possessed a personality that was well-suited to drawing people to him. People would expect, on first meeting him, for him to be overly stiff and somewhat pensive, and given the amount of problems he was dealing with at the time that was to be expected. Yet he was also able, amongst all the formality, to speak and act freely.

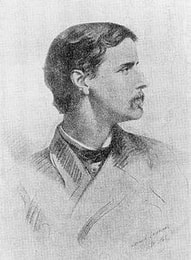

Mitford writes that Tokugawa Yoshinobu was an individual who possessed many excellent traits. He was of short stature in comparison to Westerners, but around average for the Japanese of his day. When he wore more traditional clothes, that difference was not really all that obvious. Mitford wrote that among all of the Japanese that he met during his time in Japan, Yoshinobu’s figure was the one that was the most impressive to Western eyes. He says that he had a bright, healthy olive complexion, with sparkling eyes. While his mouth was stiffly pensive, he had a kind expression when he smiled. He had a strong body, which was very masculine in appearance. He also practiced horse riding regularly, and in all weather like a famous English huntsman. Forty years after their first meeting, Mitford said that the passage of time had hardly aged Yoshinobu. His attractive gait had not diminished any, and while he might have had more wrinkles on his face, his character had not changed at all. One of the peculiarities of being born into a famous household is that everything is done according to tradition. Yet Yoshinobu, as an aristocrat, was exceptional. Mitford regretted the fact that Yoshinobu’s position in society was anachronistic, however.

Mitford then writes that after engaging in friendly conversation for around an hour, Yoshinobu mentioned that he would like to see the guard that the delegation had brought with them, and which had been waiting in the central grounds of the castle. Yoshinobu appeared to be quite impressed by the sword and lance drill conducted by the mounted troops. Yet what impressed him most was the size of the horses they had brought with them, which were a type of Arabian breed they had imported to Japan from India and were quite grand. Yoshinobu loved horses, and so spread the word that these foreign horses were, when compared to Japan’s own domestically bred horses, so much better in many ways. Japan’s own horses were, it must be said, of an ordinary type that can be found anywhere.

The Shogun then treated the delegation to a splendid dinner. He writes that at the time his diary was completed (in 1915), it was fairly standard to be treated to French cuisine at the residences of Japan’s elite. But the opportunity to dine with the Shogun and his retainers was, for the four delegates from Britain, like something out of a dream. Yoshinobu functioned as the host, while his retainers made every effort to accommodate the delegates. Mitford also mentions that Yoshinobu, at some stage during proceedings, rose up from his seat in order to propose a toast to the health of Her Majesty the Queen of England. The diplomatic practice of making toasts was not something commonly known in Japan at the time, and it appeared to be an attempt by Yoshinobu to please his guests. Parkes then returned the gesture by proposing a toast to the health of the Shogun. After the dinner, the Shogun accompanied his guests to an interior room where they were given pipes and silk tobacco purses woven by the Shogun’s wives.

Mitford also writes that as the delegates were preparing to leave, they ventured down one of the hallways in the residence which was decorated with fabulous prints depicting many famous poets. When Yoshinobu saw how much the delegates appreciated the paintings, he ordered one of them to be removed from the wall and presented to Ambassador Parkes to take back with him to the British mission. Ambassador Parkes was initially reluctant to accept the picture, however Yoshinobu told him that “every time I will look at that spot, I will know that the picture that hung there now decorates the residence of the Ambassador of Britain, and that will bring me great joy”. Mitford then exclaims “Can you conceive of any greater form of farewell than this?”

Mitford wrote that the delegates remained in the castle until after 9pm. He said that the delegates were incredibly pleased at the way the meeting had gone, and that the retainers of the Shogun were also happy to have been granted the opportunity to meet with representatives from Britain for the first time. Mitford later wrote that because of the Shogun’s natural curiosity and affability, there was a strong expectation that the opening of the port of Osaka, which was scheduled to take place in January the following year. He states that he was scheduled to be transferred out of Japan around that time, something that vexed him greatly. He believed that he would be missing out on the last politically important event in Japanese history. However fortunes changed and he ended up staying longer, and would have many other opportunities to experience ‘historically significant’ events.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed