canberratimes.com.au

canberratimes.com.au De mortuis nil nisi bonum dicendum est.

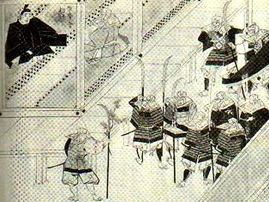

canberratimes.com.au canberratimes.com.au David Pope has brilliantly captured the mood of many Australians with this particular cartoon in this morning's Canberra Times newspaper. Let's just have quiet contemplation of the 100th anniversary of the Gallipoli landings, without the rampant commercialism and the ceaseless pontification of what it 'means' to the nation as though the rest of the war was of less importance. Gallipoli holds its own meaning for each and every individual - I note its significance, I acknowledge the sacrifices made, I stare in disbelief at the toll it took, and I mourn those we lost. De mortuis nil nisi bonum dicendum est.  kyoto-brand.com kyoto-brand.com This week I’m going to go back to a pet favourite activity of mine and provide another translation of a chapter from a book I am reading at the moment called Sōhei= Inori to Bōryoku no Chikara (Warrior Monks – The Power of Prayer and Violence) by Kinugawa Satoshi (Kodansha, 2010). For any readers of this blog who are interested in getting a much more in depth run down of the function of warrior monks in medieval Japanese temples, Mikael Adolphson’s Teeth and Claws of the Buddha is the most authoritative study of Sōhei and their function in medieval society available in English. What follows here is a mere slice of a much larger topic that has been well covered by Japanese historians for the best part of a century. There are still studies, however, that pop up from time to time that provide a new perspective on the whole phenomenon of religiously sanctioned violence and its effect on society. The chapter that follows is from just such a study. The mountain peak battle of Chōji In the latter part of the Heian period at the head temple of the Tendai sect of Buddhism, Hieizan Enryakuji, internal factional battles regularly broke out which were accompanied by the appearance of armed temple followers. These were the so-called “Sōhei” (literally, warrior monks), and were widely regarded as a symbol of the destruction of the ‘Buddhist Law’ (Buppō) that characterised this period. At the same time, and in the same way, the temple of Kōfukuji located in Nara also had its own Sōhei , and these two major temples exercised a powerful influence over the religious world of their time (this division in power between Enryakuji and Kōfukuji was known as the Nanto Hokurei, or 南都北嶺). (p.16) As an introduction to this subject, I will pay attention to an incident that took place in the 1st year of Chōji (1104) which is a typical example of the type of internal conflict witnessed at Enryakuji during the Heian period. Enryakuji comprised a large number of estates that spanned across the Mt Hiei area. The three principle estates of Enryakuji were known as Tōdō (the Eastern Tower), Saitō (the Western Tower), and Yokawa. The estates were not determined by geography, but functioned more as a political entity in which meetings known as Shūe took place. In order to preserve their territory and right to use the labour found therein, each ‘tower’ maintained an independent political stance and acted in their own interests. The temple complex of Enryakuji, which comprised these three towers, was certainly not monolithic. (p.16) The incident of violence detailed here occurred as a result of a clash between the Eastern and Western towers. The incident itself reveals in stark detail the type of armed conflict undertaken by monks in temple complexes at the time, and clarifies the role played by groups of monks (known as a Daishu) and their ties to ‘Akusō’ (literally, evil monks, 悪僧), a term often used at the time to describe such characters.(p.16) In the 7th month of the 5th year of Kōwa (1103), Fujiwara no Tadazane, the Minister of the Right to the Imperial Court, issued an expulsion order against the monks of the Western tower of Enryakuji (this information is derived from the Denryaku, a diary maintained by Tadazane dated for the 22nd day of the 7th month). The Daishu of the Western tower was spurred into taking action against Tadazane, although the actual course of action is unclear. From the 3rd month of the following year, diary entries reveal the increase in sporadic fighting between the Eastern and Western towers. It did appear to Tadazane that the age of the downfall of the Buddhist Law had arrived, given the prevalence of acts of arson and the destruction of monk lodgings by either faction. It is certainly likely that Tadazane’s expulsion order of the previous year played a role in sparking the feud between both towers. (p.16-17) While this was going on, the background story to the conflict between the towers began to reveal itself. In the 6th month of the 1st year of Chōji, a “Daishu” submitted a formal request to the Court that Gon no Shō Sōzu Jōjin (貞尋) be punished by being sentenced to exile from the temple complex (it is not clear at this point to which Daishu the diary was referring). The Daishu fingered Jōjin as being both a conspirator and agitator in the recent disturbances between the towers. When Jōjin managed to escape punishment despite confirmation of his guilt, mainly as a result of Court largess towards Jōjin, the Daishu continued to demand that he be punished. (p.17) At the same time, the Daishu charged that a monk known as Keichō (慶朝), who at the time was the head of the Tendai sect, was in cahoots with “that evil monk Jōjin” and retaliated by destroying Keichō’s living quarters. Keichō was a monk affiliated with the Yokawa tower, and fulfilled a dual role (in addition to being head of the sect) as administrator of Yokawa’s territory. On the other hand, Jōjin, Keichō’s co-‘conspirator’, was affiliated with the Western tower. Since, as a result of the request, Jōjin was denounced and Keichō had his quarters demolished, the Daishu referred to above was not that of the Yokawa or Western towers but was from the Eastern tower. The conflict from the previous year between the Eastern and Western towers had thus spread to the Yokawa tower and intensified. (pp.17-18) An attack on the head of the sect was obviously a problem for the Court, so in the 10th month the Court ordered that a Sōgō (僧綱) be convened in order to investigate the incident. A Sōgō was a meeting of various officials that transcended sect divisions and whose function was to regulate and administer the activities of monks and nuns. Whenever a problem emerged between monks, the Court took it upon itself to convene a Sōgō. Diary entries of the time note that the Sōgō would be ordered to clarify whether the disturbance affected the overall structure of Enryakuji or whether it was the result of the actions of a limited number of individuals. If the disturbance resulted in recourse to arms, the Sōgō was also authorised to dispatch warriors to the entrance to the mountain temple complex at Sakamoto (in modern Shiga prefecture). (p.18) Unfortunately no historical records remain that explain how this particular disturbance was resolved. However, from the 12th month of the same year (Chōji 1) through to the 1st month of Chōji 2 (1105) a new disturbance broke out between Enryakuji and the temple complex of Onjōji (Miidera). This new conflict obviously demanded Enryakuji’s full attention, and so it appears that the internal conflict between the Eastern and Western towers was resolved before tackling the feud with Onjōji. As Keichō resigned from the position as sect head in the 2nd month of Chōji 2, we can surmise that he took responsibility for bringing the internal dispute to an end and withdrew.(p.18) This particular disturbance, which is referred to in the Chūyuki diary as the ‘mountain peak war’, features a range of individual monks apart from those already referred to here. There are certainly many who considered these monks to be typical examples of “Akusō”. As revealed at the beginning of this chapter, these individuals, whose existence within the temple complexes of medieval Japan was so entwined with violence, certainly garner our interest as Sōhei. However the fact that these individuals were referred to as “Akusō” does not mean that diarists simply assigned to them a pejorative nuance that stemmed from an act of violence. In many instances, the actions undertaken by these individuals were sanctioned by their Daishu. In order to ensure that one does not come to conclude that Akusō were by nature outlaws, it is necessary to outline their relationship to the Daishu. This chapter will explore the various theories that have emerged regarding the “Akusō” that appear in the “mountain peak war”, and will explore the peculiarities of the age that gave rise to such figures. (pp.18-19)  blog.goo.ne.jp blog.goo.ne.jp Last week the Australian Security Policy Institute (ASPI) launched a paper by Andrew Davies and Benjamin Schreer exploring the strategic dimensions of adopting 'Option J', the name (allegedly) given to the plan to purchase submarines from Japan within the Department of Defence. Ever vigilant to point out the potential pitfalls of any such decision, on Tuesday ANU academic Hugh White added his two cents to the argument (which can be viewed here). According to White, Australia's adoption of Soryu class submarines would leave us at the mercy of Japanese strategic planning, because Japan would reveal as little information about the Soryu to Australia as possible, thus making Australia wholly dependent on Japan for the operation of its submarine fleet. Does this sound like a plausible scenario? It presupposes that Japan's primary motive in offering submarine technology to Australia is to ensure that Australia (or more accurately, its submarines) cannot operate independently of Japan. Would Japan jeopardise its burgeoning security relationship with Australia by presenting us with a zero-sum option, and would Australia accept such a deal in the first place, given that (in White’s view) it surrenders Australia’s security interests to those of another country? Australian defence planners cannot be as naive as White portrays them. Despite the political turmoil surrounding the future submarine choice, the existence of a comprehensive evaluation process and its study of alternative models for Australia suggests Defence has been exploring different submarine options for Australia for some time (and it has, at least since the 2009 white paper was released), and that on its advice government agreed to change tack and consider other choices. The future submarine program could certainly prove beneficial to Japan's heavy shipbuilding industry and mark the entrance of Japan into the world arms trade market, yet Japan knows what the politics of the submarine debate are, and would hardly want to make it even more difficult for Australia to reach a decision by withholding information (the commercial rivals for Japan in Germany and France make a compelling case for revealing information, as any lack of detail would, presumably, impact heavily on the final decision). Look at things from a Japanese perspective. What does any potential deal with Australia do for Japan? Firstly, it presents training opportunities for the Japanese shipbuilding industry because the insistence of Australia on local involvement would compel the industry to cooperate in improving local Australian skills and efficiencies. Australia's role in the region, and its fairly benign security stance, would allow Japan to embark upon military equipment sales without the potential for severely upsetting its nearest neighbours. It would open up an entirely new area for Japanese industry, thereby producing jobs in a sector competing with Korea and China for work. It would allow Japan to extend its potential security partners beyond the US, the first time since 1945 that this will have occurred. It would give Japan the option of working with a regional partner that does not have the same 'baggage' as the US (or history of occupation under Japan). If Australia was to reject defence cooperation with Japan on the grounds that it would be too destabilising for its relationship with China, what message would that send to other democracies in the region about Australia? It certainly wouldn’t garner confidence, even though it might placate China until the next potential conflagration. White is convinced that Japan is on a collision course with China and is prepared to take the US and Australia down with it in any future conflict with China. Rather than seeking to diffuse regional tensions, White regards Japan as a catalyst for conflict because Japan would not agree to any Chinese leadership of Asia given this would conflict with Japan’s image of itself as a great power (White, The China Choice, Black Inc, Collingwood, 2012, p.86). Leaving aside questions of whether Japan does see itself as a ‘great power’ (precedents, as outlined here (J), tends to suggest that it doesn’t, or certainly not in line with any agreed definition of ‘great power’), Japan recognises that the power balance in the region is changing and is not trying to halt that process. At the same time, it does recognise the need for a more pro-active role on its part in ensuring peace and stability in the region and further abroad (MOFA, Diplomatic Blue Book 2015, p.29 - J). This means managing risk through greater cooperation with other states, China included. The assumption by White, as well as Sam Bateman (found here), is that any future scenario for China-Japan relations is conflict, and that any security relationship with Japan in the form of submarines would place Australia firmly in China’s sights. Therefore take the European option and avoid the risk. Yet if we are looking at future scenarios, any submarine acquisition by Australia could potentially result in conflict with our neighbours, and any regional conflict could potentially result in Australian involvement. If Japan is offering to share its expertise in submarine building, this immediately benefits Australia’s navy and manufacturing industry while simultaneously strengthening relations between nations in the region. China may eventually come to surpass Japan economically and technically, yet Australia will have benefitted enormously from its security ties with Japan. We can recognise and mitigate risk without falling prey to our own insecurities. |

AuthorThis is a blog maintained by Greg Pampling in order to complement his webpage, Pre-Modern Japanese Resources. All posts are attributable to Mr Pampling alone, and reflect his personal opinion on various aspects of Japanese history and politics (among other things). Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

|