Takeda Isami, “Monogatari – O-sutoraria no Rekishi: Tabunka Midoru-Powa-- no Jikken”, Chūkō Shinsho,

The ‘White Australia’ (Hakugō shugi) Nation

What was “White Australia”?

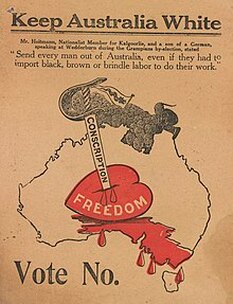

Australia was previously known as the “Hakugō shugi” nation. Hakugō (the pronunciation of the characters in Kanji) means “White Australia”, or more specifically, “Australia for white people”. It refers to the creation of a society with British origins and primarily made up of Caucasians. When casting an eye back over world history, it was the first instance where a policy of racial discrimination was adopted at the federal level and made Australia synonymous with racial discrimination.

A policy of racial discrimination that placed Caucasians at the apex of society was not something unique to Australia, and shared aspects of its idealism with other colonies settled by immigrants from the United Kingdom including New Zealand and Canada. However the ‘White Australia’ policy, which legalized racial discrimination, was deemed indispensable to the creation of the nation. Australia, through various forms of media, strongly advocated this policy.

The terms ‘Hakugō shugi’ (‘White Australian-ism’) and ‘Hakugō seisaku’ (‘White Australia policy’) were not based on legal definitions but were, at best, common terms of reference used by both politicians and the media. The legislation that enabled the White Australia system was called the “Migration Restriction Act” (1901). Japan itself had immigrant restriction laws which placed restrictions on what activities migrants could undertake based on whether they were permanent or temporary migrants. Hence a more accurate translation of these would be ‘migration restriction laws’.

The Australian Migration Restriction Act didn’t suddenly spring to life in 1901, however. Australia’s colonies had their own legislation which, in the latter half of the nineteenth century, sought to ban Chinese or other persons of colour from settling there. The Migration Restriction Act merely consolidated these various migrant acts into one overarching piece of legislation, and was the end result of already well-established practices. It was the culmination of a demand for answers to problems that beset the nineteenth century.

So why did Australia deem it necessary to introduce a national policy with such a striking name? Looking at it from the point of view of the present day, it is impossible to avoid the policy’s association with racism. Yet to Australians at the time of its introduction, it was a core strategy essential to the protection of the nation. Australia, which began as a small, overwhelmingly Caucasian society, had seen a rapid influx of foreign labourers of Asian extraction in the nineteenth century which threatened the very foundations of Australian society (or so it was believed).

There were no tourists at that point in time, and those seeking to enter the country were either white labourers looking to permanently immigrate or else non-white (coloured) non-skilled labourers brought into the country on contracts of a few years’ duration. Most of the coloured labourers were Asian, and a majority of these were Chinese. In modern society, the term ‘coloured’ is discriminatory and is not used, with ‘non-white’ the preferred alternative. However historical records from the time used ‘coloured’, it shall be the term used here. Also, since ‘non-white’ is a modern term, it won’t be used in order to avoid confusion. Incidentally, the term ‘coloured’ continued to be widely used up until the end of the Second World War.

The Chinese did not come as immigrants, but by and large sought to enter Australia as ‘contract labourers’ in order to undertake simple laboring tasks. In Japan, it was common knowledge that Australia sought to limit the intake of Asian migrants, but in truth this policy was predominantly aimed at ‘contract labourers’. With the passage of time, many of these Chinese labourers began to operate grocery businesses, laundries, furniture, and small scale farms in the vicinity of major cities. This then led to a rapid growth in permanent settlement.

During the colonial period, laws had been introduced to prevent such settlement. Yet these were undeveloped, and so Chinese societies began to spring up within the central districts of Sydney and Melbourne. Since there was no movement of labour from either Central or South America, or from Africa, a majority of the labour movement into Australia was confined to either the Asian region or the South Pacific. Most of the labourers were either Chinese, Japanese, or Indian, or else Kanaks from the South Pacific.

In order to deal with the large inflow of Asian labourers to the country, itself a prelude to Chinese settlement, a large number of Australians agreed with a proposal to severely limit the intake of coloured people into the country, focusing on Asians in particular. The end result of this was the formation of ‘White Australian’ society. As far as Australia was concerned, this society was the ideal, and was adopted into the creation model for the Commonwealth. The legislation banning on principle the entry into Australia of Asian labourers became the Migration Restriction Act, which was the first Act passed by the newly formed federal Australian parliament.

The formation of the Migration Restriction Act – a Christmas present

The Christmas present awaiting the people of Australia at the turn of the twentieth century was the Migration Restriction Act. On the 1st of January, 1901, the Commonwealth of Australia was formed, with the first order of business for the new federal parliament being the said Act. It was introduced to Parliament by the first Prime Minister, Edmund Barton (January 1901 to September 1903). Following extensive debate about the “coloured question”, it unanimously passed both houses on the 23rd of December and was signed by the governor-general just in time for Christmas.

Under the law, during the colonial period the resident governor, and then once federation occurred the governor general, was responsible for signing any legislation. Any unsigned legislation was not considered to be in effect. Approval by either the governor or governor general meant that the legislation had been formally approved by the British government. For more than half a century following its creation, the Migration Restriction Act carried on its task of legally excluding any potential Asian labourers or those wishing to immigrate to Australia.

The ‘coloured question’ debated by parliament was predominantly one based around arguments concerning Chinese, Japanese, Indians, and Kanaks. The large number of Chinese were regarded as a problem; the Japanese, while fine people, were considered a threat; while the Kanaks were regarded as a problem from the point of view of abolition of the slave trade. The debate ultimately concluded by restricting all coloured migration, yet it did point to the problem of characteristics peculiar to each group. Debate on Indian migrants was the most lax, but this had more to do with the fact that debate on the Chinese, Japanese and Kanaks had come before it and not because of any perceived lack of urgency in debating about Indian immigration.

Abolition of the slave trade

One particularly interesting point about these debates was the occasional reference to America as an example of what not to do. Australia was conscious of and had a history of referring to the American experience during the process of building the United States, with one particularly controversial subject being slavery. There was a shared view in Australia that the growing seriousness of the ‘negro problem’ in the US meant that Australia should not follow in America’s footsteps by introducing its own system of slavery. Even today, there are few people of African origin living in Australia. The reason their presence never became a political problem was because of the harsh lessons learned from the US.

As we will see later on, Australia in the nineteenth century did make use of a ‘type’ of slavery. This was an age in which many Kanaks were arranged to be brought from the Solomon Islands and the New Hebrides (modern Vanuatu) to Australia, where their indentured labour on Queensland sugar plantations became the norm. However the emergence of a political view that refused to countenance the incorporation of a slavery system made up of coloured people led to debates in parliament, with those opposed to the importation of Kanaks eventually winning the majority of votes. This signaled the end of the colonial era slavery system. Moreover, as a result of the ban in principle on migration by coloured people to Australia, a side product of this was the simultaneous adoption of the South Pacific Islander Labourer Act (1901) which was the final nail in the coffin of slavery. The Act essentially abolished slavery, hence both it and the Migration Restriction Act were landmark pieces of legislation.

The mechanism for excluding Asians

In what way were Asians excluded from entering Australia as a result of the Migration Restriction Act? The mechanism for entry into the country was extraordinarily simple. If you were Caucasian, you could enter the country without question. If you were a person of colour, you would be refused entry. It was plainly obvious that refusal was based on the colour of the applicant, yet a condition for entry was the educational level achieved by the applicant. This came in the form of a language dictation test. The mechanism at work here saw Asians and other people of colour having to take a test which nearly all of them failed.

The test was not conducted in English, but in one of a number of selected European languages and consisted of 50 questions in all. If the Asian person applying was proficient in French, the test would be conducted in German. If they were proficient in French and German, then they would be presented with questions in either Italian or Spanish. The words used in the dictation test were prepared from a wide variety of sources, including some European minority languages. It was a system that ensured that even if the applicant was a well-educated Asian labourer, they would fail to pass.

Before the test was established, it may have been possible to gain entry by passing the dictation test, but what needs to be understood is that in reality passing the test was nigh impossible. The adoption of this customs system as a national strategy made the White Australia policy an infamous example of racist policy making.

A racially discriminatory system that selected immigrants based on their skin colour was bound to cause friction in the colonies, which was why Britain first adopted a system of educational selection (re: discrimination) for the South African colony of Natal in 1897. It signaled the birth of the Natal system of discrimination against coloured people based on tried and true methods and an amalgamation of laws. This system was then suggested to Australia by British Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain. Australia later adopted the Natal system as a migration control mechanism. The dictation test itself lasted until 1958, meaning that this system lasted over half a century.

Why was this test applied to Japanese migrants?

It is a little known fact that the original draft of the Migration Restriction Act had Japanese applicants in mind when it incorporated the use of an English language dictation test as part of its provisions. The English language test took into consideration the ‘face’ (or pride) of Japanese applicants, and was proposed by Prime Minister Edmund Barton after mulling over both anti-Japanese sentiment in Australia and British-Japanese relations. Hardline supporters of the White Australia policy were opposed to including an English language test, which is why it ended up being substituted with European languages.

In the background to Barton’s proposal lay a number of conflicting issues.

Firstly, Joseph Chamberlain sent secret correspondence to Prime Minister Barton in which he demanded that Barton consider the situation in the Far East. At the time, Britain was engaged in highly secret negotiations with Japan concerning the creation of a Japan-UK Treaty (ratified in January 1902). Clearly Barton must have been paying attention, because the final stage of treaty negotiations happened to coincide with the introduction of the Migration Restriction Act (December 1901). Chamberlain never explicitly mentioned the negotiations, but given the special place occupied by Japan in British thinking, Barton certainly understood their implications. It goes without saying that the Japanese government made its objections to the introduction of the Act known to the Australian government via its embassies in London and Sydney.

Secondly, Japanese labourers were needed domestically. The Japanese had a relatively high level of functional English language ability and there was a growing demand to bring in Japanese labourers to contribute to the development of the nation. This was certainly something of which PM Barton was well aware.

Thirdly, Australian and British trading companies made their objections to the law felt. If the Japanese weren’t able to enter Australia, these companies warned, then there was a possibility that this would cause problems in the sale of Australian wool, dairy products, and meat products to Japan and other Asian nations. This could then jeopardize the burgeoning wool trade. It was just because of these concerns that a decision was made to incorporate an English language test into the Act. This illustrates the existence of a political decision that would make a special exemption for the Japanese while continuing to exclude both Chinese and Kanaks.

Despite such a highly placed decision, Barton’s proposal was ultimately overruled by the voices of hardline supporters of the White Australia policy. There are two reasons why the proposal ultimately failed. First, the Labor Party, with its call for White Australian nationalism, made their objections to exemptions for any persons of colour felt and refused to compromise. Moreover, speeches by the influential conservative politician Alfred Deakin, who was standing for election in Melbourne, ended up burying Barton’s proposal. Deakin, who plainly believed that the ‘superiority’ of the Japanese made them dangerous and thus in need of exclusion, was the leading figure in the debate about the threat posed to Australia by Japan. He would later go on to become prime minister.

Second, if an English language test was used, there was a danger that this would shut out migrants coming from the European continent. This was more of an issue related to the proposed system itself. While the government had no intention of using language dictation tests on migrants from Europe, if for the purposes of conformity an English language test was incorporated into the Act, then this would place European migrants at a disadvantage and run the risk of extinguishing European interest in migrating to Australia. It was for these reasons that the English language test was abandoned and a test using European languages employed instead.

Exceptions exist for everyone - The acceptance of wealthy Asians

Despite introducing the White Australia policy, the Commonwealth government did not entirely shut off Australia to Asians. There were exceptions made for a variety of countries.

So what sort of Asians were able to meet the criteria for these exceptions? Namely, those with financial power, technical know-how, and/or character. Character by itself was not enough, so it had to be backed up by either financial power or technical ability.

The peak in Asian permanent migration to Australia in the early 20th century occurred immediately before the introduction of the White Australia policy (i.e., 1901). Thereafter, for over half a century, the number of permanent migrants continued to fall. In 1901 there were 30,542 Chinese residents in Australia. By 1921, this had fallen to 17,157. Later in 1947 numbers dropped through the 10,000 line to 9,144. Japanese migrant numbers also fell dramatically, from 3,554 in 1901 to 2,740 in 1921 to 157 in 1947. The main reason for this was the outbreak of conflict between Australia and Japan during the Second World War. The smallest drop in numbers was experienced by the Indian community. From 4,681 in 1901, their numbers fell to 3,150 in 1921. Thereafter their numbers remained fairly steady, dropping to 2,189 in 1947.

While there were dramatic falls in immigrant numbers, they never fell to absolute zero. Asians continued to live in the Australian community, and while they might have temporarily departed the country, they were still allowed to re-enter. These were the people that Australian society decided had economic merit. Major exceptions were made for entrepreneurs with large amounts of collateral, trading companies that were contributing to exports, and experts that possessed detailed technical knowledge. Kanematsu Shōten made a considerable contribution to Australia-Japan trade (previously known as Kanematsu Goshō, it underwent a name change in 1990 to Kanematsu). Many divers who were involved in collecting pearls for the company came from Wakayama Prefecture and were classified as ‘technicians’.

Half of those Asians that entered Australia were men, with very few women allowed. The reason for this was evident. It was to prevent the mechanism that gave birth to Asians, which would then naturally increase the number of Asians in the country. From the nineteenth century through to the early twentieth century in Australia, Caucasian women on average gave birth to 5 to 6 children. As there was a strong fear that Asians were capable of creating larger households than Caucasians, passage to Australia was limited to singles. However a small number of wealthy immigrants and technical specialists were allowed to bring their wives with them.

The restrictions were easiest on the Japanese, followed by the Indians, and then finally the Chinese. The Chinese not only made up the largest ethnic Asian community, they also had the largest disparity in wealth and education, with the largest number of unskilled labourers. At the time, most of those working below decks on Australian and British ships were Chinese. Whenever a ship with Chinese crew weighed anchor in either Sydney Harbour or the Port of Melbourne, customs procedures dictated that all Chinese crew had to possess an identification card (with picture attached) and had to submit to giving finger prints. These conditions were not imposed on either the Japanese or Indians. This meant the problem of smuggling involving Chinese ship crew members had become common enough to warrant customs measures specifically aimed at the Chinese.

The standards applicable for granting exceptions for Asians gradually changed as well. After Australia became a ‘white’ country following the passage of the Migration Restriction Act, the bureaucratic measures applied to implement the Act became exceedingly complicated. When seeking to re-enter the country after travelling abroad, Asians who possessed a residency card would be permitted to enter. This was later changed to proof of ownership of property in Australia. Furthermore, if accompanied by a spouse after returning from overseas, there were times when entry might be granted or refused. For example, there were cases in which entry was permitted but limited the spouse to only six months’ residency in Australia. Yet it was also possible to extend the period of residency to a year. Exceptions were also made for wealthy Chinese entrepreneurs to enter with their wives and families. So one can only conclude that the bureaucratic measures concerning entry were applied randomly.

Why did the Chinese become the target of exclusionary measures?

The concept of White Australia had the Chinese as its main target. Both anti-coloured and anti-Asian movements were so limited in the scope of their activities that they could effectively be described as anti-Chinese movements. Other people of colour, such as the Japanese, Indians, and Kanaks, merely existed of the periphery of these movements. As such, it would be worthwhile to examine the processes that were employed to expel the Chinese from Australia.

From the nineteenth century onwards, the process of expulsion was divided into three stages. The first stage involved economic causes, the second stage then shifted to social causes, while the third and final stage involved political causes.

(1) Economic causes – The group that felt most threatened by the Chinese from the very outset were blue-collar Caucasians. The involvement of the Chinese in the development of gold mining in Australia, which they undertook for low wages, led to a large drop in the wage standards of Caucasians working in the same industry. We can summize that the lead cause for the expulsion of the Chinese at this stage was the appearance of ‘poor whites’ and their economic grievances. From the 1870s through to the 1880s, the employment of Chinese labourers began to diversify, which was accompanied by an increase in complications concerning Chinese labour.

In 1878, Australia experienced a large scale strike by ship workers. The impetus for this strike was the decision by the Australasian Steam Navigation (ASN) to hire Chinese labourers to crew their ships. Both British and American steamship companies had opened up international competition and the routes to and from Australia were fair game. The same steamship companies began to employ the Chinese in order to secure greater international competitiveness for themselves. At the time, the average wage of a Caucasian stoker was 6 pounds a month. By contrast, a Chinese stoker earned half that at 2 pounds, 75 shillings a month.

The ASN ran fixed cruise lines along the east coast of Australia, centered on Sydney, but travelling to Melbourne and Brisbane. It also opened up routes to New Zealand, New Caledonia, and Fiji. As these routes were also used for delivering mail, the colonial governments of both New South Wales and Queensland provided subsidies to the ASN, thus making the company quite influential. When a route to Hong Kong was opened up in 1878, arrangements were made to hire a Chinese crew, who then boarded the ship and were brought back to Australia. It soon became clear that the jobs of white crew members had been snatched away by the Chinese. The ship workers’ union then set about organizing the first mass strike, which paralyzed the fixed shipping routes.

We must not forget the existence of those white labourers who had their employment taken away by Chinese workers and those entrepreneurs and industrialists who had hired Chinese in the first place and then reaped the rewards. It helps to explain why these unemployed whites became the spearhead of the Chinese expulsion movement and were the most fervent supporters of the White Australia policy. As far as these white labourers were concerned, expulsion of the Chinese meant the total expulsion of all Asian labourers from Australia. They would not countenance any other arguments.

As we will see later on, the same labour questions would be applied to Afghans plying their trade with their camels. Afghans were brought into the country together with their camels in order to contribute to overland transport. Yet this resulted in the halving of revenue available to Caucasian carriage drivers and the laying off of auxiliary staff. Transport companies that plied the dry, desert areas of the country also knew that horse drawn carriages belonging to whites had no chance of beating the Afghan camel trains. While this is but one example, it is no exaggeration to say that the problem of Asian labourers was on a scale that covered the entire nation.

(2) Social causes – Social causes refers to the display of hostility by Australian society as a whole to the Chinese residing in that society. Since the Chinese were limited to living in certain regions, and given that their communities were concentrated in those regions, smaller region towns located near gold mines tended to have larger Chinese populations than the local Caucasian community. The different lifestyles and cultural habits of the Chinese gradually drew the ire of the Caucasian residents to the point that the very existence of the Chinese community was regarded as a problem.

As these Chinese communities occasionally harboured smallpox victims, the Chinese were regarded as the leading cause for the outbreak of the disease. Smallpox was an infectious viral disease that also affected the poor white districts of Sydney, but the Chinese became the target for criticism. In caricature pictures drawn at the time, the Chinese were represented as strutting about in groups with long braided hair and smoking opium pipes. The message such pictures sought to convey was that this scene should not be tolerated by Australian society. In the same way that the human body sought to expel any foreign matter from it, white society began embrace feelings of loathing towards the presence of ‘yellow races’. This was the point at which economic reasons for anti-Chinese sentiment switched to social reasons, and the White Australia policy began to be more widely accepted by those with similar values.

(3) Political causes – The final stage of the adaptation of the White Australia policy involved the political classes. The ideal picture of white society had been sullied by the presence of Chinese labourers, and there were real fears that their existence would prove fatal to the plans to create an ideal society. It was a sentiment widely shared among white society. Given that Chinese labourers had brought down the average wages of white blue-collar workers, the Chinese created economic problems. This gave rise to a consensus among the citizenry that society could not allow this problem to fester, and so moves began to find a political solution. The Chinese question proved to be an elixir that gave rise to a sense of unity among whites, and the ‘White Australia’ policy became the focal point for a Caucasian-driven large scale social movement. Within the parliaments of various colonies, attention was given to legislative procedures aimed at expelling the Chinese, with both Chinese exclusion laws and coloured exclusion laws arranged separately. The sense of unity among whites transcended colony borders and fermented, eventually transforming into the push for federation. All of this political will found its final expression in the creation of the Commonwealth. This unity then brought about the amalgamation of all of the above laws into the Migration Restriction Act (1901).

The influx of foreign labourers

- Chinese, Japanese, Indians, Kanaks –

Why was there such a large increase in Chinese immigrants to this new continent in the nineteenth century?

The biggest reason lay in the abolition of the slave trade. Britain announced the end of slavery in that country in 1833. About the same time, the East India Company ceased to hold a monopoly over trade with China. This made it possible for other private British enterprises to freely enter the Chinese market. The Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 also announced the end of slavery in the United States. All this coincided with the abolition of the British transportation system in the 1840s, in which criminals were previously sentenced to exile abroad. Meanwhile Australia was suffering from a critical shortage in labour necessary to cultivate the new continent.

One measure adopted to resolve the labour shortage problem was to use the Chinese. The Chinese were employed in great numbers in various fields of endeavour, including the development of gold mines. The Arrow War (also known as the 2nd Opium War of 1856-1860) resulted in the defeated Qing Empire signing the Treaty of Peking (Beijing) with Britain and France. The treaty included clauses that gave public approval to foreign agents employing Chinese labourers within the treaty ports. This provided a legal basis for British merchants and trade companies to then begin sending large numbers of Chinese labourers to Australia, the US, and Canada.

The Asia-Pacific saw a rapid escalation in labour movement centered on China during the nineteenth century. The 1850s bore witness to the discovery of gold in both the US and Australia, which heralded the beginning of the era known as the “gold rush”. As in the United States, investors and developers in Australia began examining the systemic importation of Chinese labourers as a cheap source of labour to help develop gold mines. In response to this, British and American shipping, trading, and HR companies located in Hong Kong, Macau, and Amoy (Xiamen) began to send vast numbers of Chinese labourers, referred to as ‘coolies’ (on account of the Chinese characters used to describe their work – 苦労) to Australia and the United States. Some of those companies included, from the British side - Jardine Matheson, John Squire, Glover, and P&O. The Americans, with their interests centered on Shanghai, were represented by companies such as Russell & Co. Jardine Matheson, who established themselves in Canton in 1832, shifted their head office to Hong Kong in 1841 and thereafter became well known for their trade in opium.

These US and British representatives engaged in fierce rivalry with one another in the China trade ports. Using British agents, a majority of those Chinese labourers sent from Hong Kong, Macau, and Amoy aboard transport ships ended up on the east coast of Australia. However others sent to West Australia first went by way of Singapore, which was geographically closer (to southern China).

The spread of Chinese cuisine

The international movement of labourers naturally led to movement in cuisine culture. Half of all those Chinese who left China were from the modern province of Guangdong (Canton), and their cuisine would go on to dominate the Chinese enclaves, or ‘towns’, that sprang up in both the US and Australia. While there were certainly plenty of labourers stemming from Fujian province, the majority were from Guangdong. Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane all witnessed the formation of ‘Chinatowns’ within their precincts, while the US saw these emerge in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and New York, Piccadilly Circus in London in the UK, and in Paris. The Chinese in Britain and France, unlike those who went to Australia and North America, were not contracted labourers sent to work in gold mines.

Chinese society in London was predominantly made up of sailors from Shanghai. In contrast, and in order to compensate for a loss in labour strength stemming from WWI, Paris had a history of ‘coolies’ coming from Canton to work in construction projects. Paris in the present day also plays host to a large Vietnamese refugee community, which has contributed to the diversification of the food culture in the resident Chinatown. Sydney’s Chinatown, which was built on a foundation of Cantonese cuisine, began to adopt elements of Peking cuisine from the 1980s onwards. However Cantonese cuisine still remains the dominant Chinese food culture in Sydney.

Not migrants, but contracted labourers – the labour allocation system

While it is generally agreed that the racist White Australia policy excluded Asian migrants from Australia, in reality the law targeted Asian labourers, not migrants. The image of Asian labourers as it was conceived then is similar to that of the Asian labourers that you see working in Japan today. From the 1970s through to the 1980s Asian migrants began to be accepted by Australian society as a whole, yet even before this time Asian immigration was not really considered a problem.

Migrants and foreign labourers are by and large motivated to move for economic reasons. However, while migrants can pre-qualify as either temporary or permanent, labourers rely on pre-determined periods of contracted employment, thereby making their circumstances completely different.

Asian labourers that worked in Australia during the nineteenth century were referred to as “contract labourers”. Following the lead established by the Chinese, these included Indians, Afghans, and Japanese, and eventually broadened to include Melanesian workers from the South Pacific known as Kanaks. These labourers tended to be employed by and divided up between select private industries, all of which contributed to the development of Australia’s labour power from the 1860s through to the 1880s.

Indians and Afghans were brought by the British from the Indian subcontinent in order to contribute to the development of the interior region of Australia known as the ‘outback’. While the Chinese were predominantly sent to work developing gold mines, the Japanese went into industries such as pearl diving and to plantations where they harvested sugar cane. The Kanaks were also involved in sugar cane harvesting, and many of them were employed by plantations.

In the British territory of Fiji, Indians, who were referred to as the ‘vanguard’ of ‘Australian imperialism’, were employed by sugar cane plantations.

However by the close of the nineteenth century, the existing system of division of labour began to collapse and Chinese workers began enter a far broader range of occupations. While previously confined to working in gold mining, by 1891 most Chinese in Australia were market gardeners with mining dropping to second place. Many of those Chinese became permanent settlers, thereby actively contributing to the diversification of the labour force while initiating the process whereby they could build wealth.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed