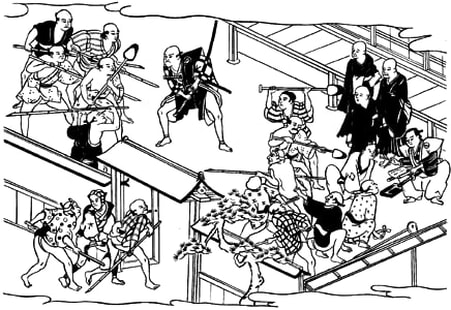

The Battle of Mikata ga hara. Source: Wikipedia.

The Battle of Mikata ga hara. Source: Wikipedia. Ieyasu’s independence from the Imagawa and first clashes with the Takeda

Tokugawa Ieyasu and Takeda Shingen did not start directly corresponding with one another until Eiroku 11 (1568). Irrespective of whatever this might show about their intentions, it is true to say that Ieyasu did not factor into Shingen’s thinking until around Eiroku 5 (1563). As is well known, Tokugawa Ieyasu (known as the time as Matsudaira Motoyasu) had been raised in the household of Imagawa Yoshimoto and had been appointed as the lord of Okazaki Castle. Although he resided in Sunpu province, this area had been amalgamated with Mikawa province. Ieyasu had been married to the legitimate daughter of Sekiguchi Ujisumi, one of the Imagawa household’s principal retainers, who went by the name Tsukiyama-dono, and was associated with the Imagawa family’s board of councillors. Unlike the prevailing view about him, Ieyasu was not a hostage of the Imagawa, but was a key member of the Imagawa household responsible for the administration of Mikawa. He could also be said to have been an influential kokushū (or regional landowner or administrator).

As Ieyasu had been under the protection of the Imagawa since infancy, the Matsudaira family of Okazaki were also protected by the Imagawa, with the administration of their household seen to by their officials. The Imagawa had appointed the Matsudaira to build the framework for both the politics and military security of Mikawa by placing them on the frontline opposite the Oda family of Owari province. Without the Matsudaira presence, the transformation of Mikawa into part of the Imagawa fiefdom would not have occurred. For the Matsudaira themselves, by being part of the Imagawa’s security network, they were able to achieve a certain degree of prominence. It was in this environment that Ieyasu continued to grow and develop.

Meanwhile Imagawa Yoshimoto succeeded in stabilizing his rule over Mikawa. If preparations for an invasion of Owari province proceeded without interruption, as a kokushū level lord there was a strong chance that Ieyasu would have been given permission to return to Okazaki. Yet fate had something else in store for him. On the 19th of the fifth month of Eiroku 3 (1560) at the Battle of Okehazama, Imagawa Yoshimoto was defeated by Oda Nobunaga and was killed in battle. At the time, Ieyasu was resident at Ōdaka Castle in Owari province on the front line of the conflict. However (after Yoshimoto’s death) he withdrew together with the entire Imagawa army and returned to Okazaki Castle. Under orders from Imagawa Ujizane, after returning to Okazaki Castle Ieyasu immediately became involved in conflict against Mizuno Nobumoto, the lord of Ogawa and Kariya Castles and an uncle to Oda Nobunaga. Ieyasu was just 19 years old at the time.

The conflict between Ieyasu and the Oda started in Eiroku 4. In the 4th month of the same year, Oda forces invaded Mikawa under the command of Nobunaga, where they proceeded to seize control of all of Kamo-gun west of the Tomoegawa river. This obviously put Ieyasu in a precarious position. Both the Matsudaira and Imagawa forces were pressed hard at this time, yet Imagawa Ujizane, currently resident in Sunpu, showed no inclination to send reinforcements to aid them. Ujizane was rather more concerned with dispatching forces in the direction of the Kantō region. At the time, Hōjō Ujiyasu had been steadily building his control over the Kantō. From the 3rd year of Eiroku onwards, he began to be on the receiving end of attacks from Nagao Kagetora of Echigo province (later known as Uesugi Kenshin).

Kagetora, using the authority of the former Kantō Kanrei Uesugi Norimasa, joined together with samurai of the Kantō and former members of the Uesugi household to resist the encroachment on their territory from Hōjō Ujiyasu. Once Ujiyasu was dealt with, Kagetora could then proceed to seize control of the Kantō region. Ujiyasu was not one to sit on his hands and straight away made a request for assistance. However assistance for Mikawa was not forthcoming. Concerned about the impending danger to him, Ieyasu made a truce with Nobunaga, which in turn would lead to an alliance. According to the prevailing view, the role of intermediary for the meeting held in the 2nd month of Eiroku 4 was Nobunaga’s uncle Mizuno Nobumoto (he who had previously been at war with Ieyasu).

However the belief that Ieyasu visited Nobunaga at Kiyosu Castle (in Owari province) and there made an alliance with him was a fabrication made up by later generations. There’s no evidence to confirm that this event ever took place, and Ieyasu certainly had no leeway to suddenly leave Okazaki in order to travel to another province. It’s understood that the alliance came about both through an exchange of documents and the coming and going of messengers. Thereafter, as previously explained, Nobunaga seized control of one part of western Mikawa province. Given that there is no trace of him having clashed with Ieyasu during this process, it is safe to say that the truce and alliance were already in place by this time.

From the 3rd month of Eiroku 4 through to the ‘leap’ 3rd month of the following year, Ieyasu was engaged in subduing the Asuri-shū of Kamo-gun in Mikawa province. In the 4th month, he moved to commence an attack on the Imagawa, launching campaigns against Kira Yoshiaki of Tōjō Castle and Makino Narisada of Ushikubo Castle consecutively. Imagawa Ujizane recognizing these as hostile acts, described them as “the betrayal of Matsudaira Kurando (a position title ascribed to Ieyasu)” and “Okazaki’s betrayal”, sent out a notice to all that he was now engaged in a full-blown war against Ieyasu. This also signalled Ieyasu’s complete independence from the Imagawa.

The start of relations between Ieyasu and Shingen

As far as can be discerned from existing historical records, the first time that Takeda Shingen became aware of Ieyasu was in Eiroku 5 (1563). The impetus for this came from an order from the Muromachi Bakufu shōgun Ashikaga Yoshiteru, instructing Ujizane and Ieyasu to declare a ceasefire. The war against the Imagawa was referred to by Ieyasu as the ‘Sanshū sakuran’ (or ‘the war of the three provinces’), demonstrating that it had escalated into a widespread civil conflict. Mikawa was divided between Ieyasu and Imagawa supporters, leading to even more fighting. In time it became clear to Ujizane that this revolt would not prove easy to suppress.

The shōgun Yoshiteru was at the time concerned about the difficulties faced in communicating with the Kantō region as a result of the conflict, and so issued ceasefire orders to both Ieyasu and Ujizane, along with Mizuno Nobumoto of the Oda camp. He also issued instructions to Takeda Shingen and Hōjō Ujiyasu, ordering them to make arrangements for a peace treaty between the two warring sides.

It was through this process that Ieyasu came to the attention of Shingen, who at the time was in an alliance with the Imagawa and so came to regard Ieyasu as a foe. This in turn led to the formation of the struggle between the ‘Kiyosu alliance’ (of Nobunaga and Ieyasu) and the ‘alliance of Kai, Sunpu and Suruga’ (consisting of Shingen and Ujizane). In Eiroku 5, Ujizane sent out a request to Shingen for assistance in attacking Mikawa province. Indeed, it does seem that this request might have been issued one year earlier, but as a result of the situation at the time, Ujizane had been unable to launch his campaign until the following year. In the 6th month of Eiroku 5, Ujizane wrote to Shingen, explaining that “I plan to embark on my campaign in Mikawa at the outset of Autumn. I would therefore be most grateful if, as promised, you can combine with my forces at that time as I intend to make full use of your considerable strength”. However in the end Ujizane did not set out on his invasion of Mikawa at the beginning of Autumn.

Indeed it would not be until the 4th month of Eiroku 6 when Ujizane finally showed his stripes. He imposed what became known as the “Sanshū kyūyō” (a temporary raise in taxes to accompany the invasion of Mikawa). What this did, however, was plunge the Imagawa territories into strife. All those who until then had held a special privilege giving them exemption from the imposition of public taxes (such as on the raising of houses) temporarily had their exemptions revoked and were ordered to pay the compulsory added cost. As a result, groups of disgruntled regional members in the Imagawa territories gathered together to demand a restoration of their exemptions. Ujizane did restore the exemptions for both those directly serving in the campaign as well as shrines and temples that had deep historical ties to the Imagawa family. All others were forced to make their payments, which were collected in due course.

However the collection of the “Sanshū kyūyō’ created the impression within and outside the Imagawa territories that the Imagawa were rushing to launch an invasion of Mikawa. Knowing this, in Mikawa itself Sakai Shōgen Tadayoshi, a key retainer of Ieyasu’s household, laid siege to Ueno Castle up until the 6th month of Eiroku 6, unfurling the banner of revolt in the process. This trend spread throughout the province, leading to the attack against Kira Yoshiaki and Ogasawara Hiroshige at Terabe Castle in Hazu-gun.

It was around this time that Ujizane appears to have made his request for support from Shingen to launch an attack against Mikawa. Shingen accepted Ujizane’s request and immediately sent a message to Akiyama Torashige of Ina-gun in lower Shinano province, instructing him to commence a strategy aimed at forcing the ‘lord of Okazaki’ to withdraw. The Takeda had already managed to secure an informant from inside the Ieyasu camp. In an order sent to Shimojō Nobuuji of the Shinano kokushū (and lord of Yoshioka Castle), Nobuuji was to meet up with messengers sent from the informant and there make arrangements for a secret meeting. In order to prove that Shimojō was acting on behalf of the Takeda and had received the assent of the Imagawa for the meeting to go ahead, Nobuuji was given a letter from Ujizane, which he was to show to anyone who might doubt his credentials.

There has been a lot of speculation about who this informant within the Ieyasu camp might have been. It may have been Sakai Tadanao of Ueno Castle. Whatever the case may have been, it was clear that Shingen, together with Ujizane, was now firmly intent on crushing Matsudaira Ieyasu (TBC).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed