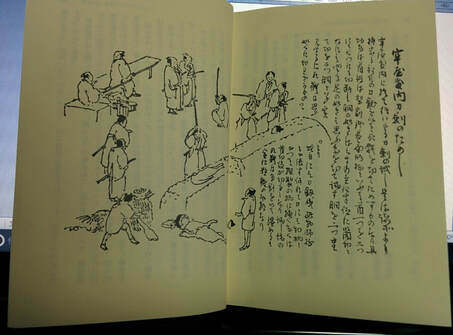

"Testing swords in the magistrate's residence" from the Edo Tokyo Jikken Garoku

"Testing swords in the magistrate's residence" from the Edo Tokyo Jikken Garoku Tonight we come to our final story. And what more appropriate theme could there be (for a book on records of crimes of the Edo period) than executions? I would thus like to spend this evening discussing the executions that occurred at the magistrate’s residence (or rōyashiki) at Kodenma-chō.

Of course, while I say executions, there were many ways in which punishments could be inflicted, from extremes such as crucifixion and being burned alive to more simple punishments such as zanzai and geshūnin (both of which still ended up with the condemned having their head cut off). Incidentally, shizai (or ‘punishment by death’) was reserved for commoners, whereas zanzai (‘punishment by cutting or slicing’) was exclusively for samurai that had fallen foul of the law. Geshūnin (literally ‘lesser person’, referring to those condemned to death) was the least ‘heavy’ of the various forms of capital punishment available, and so was also imposed on commoners. (284)

What were the differences between these three forms of capital punishment? The biggest difference, it could be argued, was how the corpse was handled after execution. In the case of shizai, the torso of the condemned, whose head had already been removed, would be carried from the ‘execution ground’ (or shizaijo) to part of the magistrate’s residence known as the ‘exulted testing ground’ (or O-tameshiba). There the torso would be sliced up in order to test the cutting edges (or ‘quality’) of the various swords belonging to the Shōgunate. The corpses of prisoners subjected to either zanzai or geshūnin would not be used to test swords, despite having already been decapitated. (285)

The expression ‘sliced up’ seems like an exaggeration, but it assuredly was not. Starting with a technique to slice the centre of the torso in half (known as ichi no dō), there were a myriad of ways in which a torso could be carved up. And not only the torso. The heads of the condemned were also subject to blade testing, and would be cut with swords or stabbed with spears. The perpetrator of these punishments was Yamada Asaemon, a hereditary name given to whomever was hired to test sword blades on behalf of the Shōgunate, together with his apprentices. ‘Asaemon’ was of rōnin (masterless samurai) status, but many of his apprentices were samurai from the regions of Japan or else their apprentices. All travelled from across the nation to learn how to ‘test blades’ under the tutelage of Asaemon. (284)

The primary purpose of ‘tameshi-giri’ (blade testing) was to guarantee the quality of the Shōgunate’s weaponry. This was why the space within the magistrate’s residence reserved for such practice was not simply referred to as the ‘testing ground’, but was the ‘exulted testing ground’ (O-tameshiba). In reality it was not only the Shōgunate’s weapons that ended up being checked for quality. Hasegawa Keiseki, born in what is now modern Tomigiwa-chō in Chuō-ku, Nihonbashi, in Tenpo 13 (1842), was the author of a visual guide to Edo in the last days of the Bakufu and the start of the Meiji era titled “Edo Tokyo Jikken Garoku” (A true pictorial record of Edo and Tokyo). A picture within that work titled “Testing swords within the magistrate’s residence” has a description attached to it, which reads,

“Swords undergoing testing within the grounds of the magistrate’s residence. These (swords) are gathered from many different places. Corpses are then cut up using both new and old swords alike”.

Hence not only the swords of the Shōgunate were tested at the O-tameshiba. Many daimyō and members of the Shōgunate’s closest retainers (the hatamoto) sent their swords to Yamada Asaemon for testing on the corpses of executed criminals. Keiseki, after his introduction on the various forms of cutting employed in testing swords, says “In truth, human bodies can’t be cut up as easily as one supposes”, thereby confirming that Keiseki himself had witnessed sword testing on corpses within the magistrate’s residence. After the Shōgun’s personal swords had been tested, Asaemon’s apprentices would take the various swords that had arrived from across the country and proceed to test them on pre-severed torsos and heads. (285-286)

Keiseki’s depiction of this scene is particularly striking. Eight figures, quite possibly apprentices of Asaemon (with a blacksmith included among them) are engaged in what appears to be nonchalant conversation while they cut up dead bodies. (288)

There were a number of detailed regulations outlining how sword testing was to take place. For example, in addition to samurai, blade testing was not to be practiced on the bodies of women, priests or shrine officials. However explaining all of the exceptions would take too long, so I’ll bring this short excerpt to an end here. (288)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed