Source: www15.ocn.ne.jp

Source: www15.ocn.ne.jp As each post will contain a chapter from the book, this will make the posts fairly long, but if you can bear with that, you might find something of interest in the details. The first chapter from the book deals with Takeda Shingen, the daimyo of Kai province (modern Yamanashi prefecture) who is regarded as one of the principal characters of the Sengoku period. So here it is, enjoy.

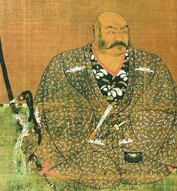

Takeda Shingen – 1st year of Taiei – 1st year of Tenshō (1511-1573)

Legitimate heir of the Shugo of Kai province, Takeda Nobutora. Infant name was Tarō. Thereafter changed name to Harunobu, and took the name Shingen after taking the tonsure and becoming a lay priest. After banishing his father from Kai and establishing himself in power, he led an invasion of Shinano province. Fought a series of engagements at Kawanakajima against the armies of the Uesugi family. Attacked and scattered a combined army made up of forces from the Oda and Tokugawa, and was renowned as the most capable military leader of his age. Before realising his ambition to secure the capital, he fell ill at Komaba in Shinano province and died. He was 53 years old at his time of death. As a talent administrator he created a series of laws known as the Koshū Hattō no Shidai which oversaw the development of mines, control and distribution of water resources, and arrangement of infrastructure, all of which had a profound impact on system subsequently carried over into the Edo period.(12)

Takeda Shingen is renowned as the general who raised the banner of “Furin Kazan” (Wind, Forest, Fire, Mountain), and as the leader of the peerless Takeda army. He was also a first rate strategist, and launched a series of invasions of neighbouring provinces from his bases in Kai and Shinano. He built military roads, developed currency, and laid the foundations of a powerful fiefdom. Even Oda Nobunaga, the man who would eventually bring the nation under his rule, bowed his head in deference to Shingen, while Tokugawa Ieyasu’s experience of facing Shingen on the field of Mikatagahara led to a humiliating defeat for the Tokugawa. If his territory had of been closer to the capital, or more correctly, if he hadn’t had to worry about his territory being harassed by the Hōjō of Odawara or threatened by the “God of War” Uesugi Kenshin, there is no doubt that Shingen would have seized power and united the nation.(12)

While I most certainly agree with these assessments of Shingen, an examination of both his military record and his achievements lead me to doubt his reputation as the “most capable general in the land.” The first thing that comes to mind when one thinks of Shingen is his war banner of “Furin Kazan”. The words inscribed on this banner were a symbol of the strategy adopted by the Takeda army. They were taken from Sun Zu’s treatise on military tactics – the Art of War – and explained how an army was to move in the field. To begin with, we’ll quote a little from the sentence preceding the famous line from the Art of War;

兵は詐を以て立ち、利を以て動き、分合を以て変を為す者なり。故に其の疾きことは風の如く、其の徐なることは林の如く、侵掠することは火の如く、動かざることは山の如し

“War, at its essence, is a process of deceiving one’s opponent. An army moves in order to gain an advantage over an opponent, and it must divide, assemble and change its shape. Moreover, an army should advance as swiftly as the wind, when it waits it should be as silent as a forest, when it attacks it should move as aggressively as burning fire, and when it is still it should be as rigidly calm as a mountain.” (13-14)

The words that followed “advance as swiftly as the wind” were those written on the banner of Furin Kazan, yet I would like to pay particular attention to the preceding sentences. The reason for this is because I believe these sentences best encapsulate Takeda Shingen’s strategic thinking.(14)

“War, at its essence, is a process of deceiving one’s opponent. An army moves in order to gain an advantage over an opponent, and it must divide and assembly and change its shape”. In these sentences, the character for a soldier (or 兵) does not merely refer to an army, but also to “battle” and “war”. The character “詐” refers to the practice of deception, or deliberately acting in a manner that disguises one’s true intention. In other words, the sentence preceding “Furin Kazan” refers to deceiving one’s opponent, of using strategy and tactics that disguise one’s true nature from an opponent. Isn’t it entirely plausible that this sentence was in fact Shingen’s hidden motto? (14)

In the Kōyō Gunkan, the principal source for records of the Takeda army’s exploits and tactics, Shingen’s famous quote is introduced, the content of which states…“The people are my armies, the people are my stone walls, the people are my moats, mercy is my ally, while evil is my enemy”. The problem with this quote, however, is that it contains language that does not really reflect the reality of Shingen’s strategies or tactics, which were characterised by their under-handed, deceitful nature. To better understand Shingen, we need to cast off the image of the “Shingen of legend” that emerged during the Edo period and pay particular attention to his exploits. By doing so, we can see just how merciless Shingen’s tactics were and how he burned with ambition to expand his territory.(14-15)

Not all of the people whom Shingen deceived were his enemies. On the 14th day of the 6th month of Tenmon 10 (1541), Shingen received word that his father, Nobutora, had departed from Kai for Suruga province. After sending troops the border between Suruga and Kai provinces, Shingen ordered them to seal the border, thereby preventing Nobutora from returning to Kai. By sending his father into exile, Shingen was then able to assume the position of head of the Takeda household. This was, if anything, an appropriate tactical debut for the man who would eventually become known as the “Tiger of Kai”. (15)

Yet there are questions regarding Shingen’s conduct during this coup. At the time he was still a young man. Politically he did not have a great deal of support, and so it is difficult to believe that he could have executed the coup by himself. Hence a question remains as to who actually created the plan behind the coup. In truth, Shingen later received a letter addressed to him from the Shugo of Suruga province, the Imagawa family, the same family to whom his father Nobutora was travelling to visit when Shingen launched his coup.(15)

Letter Sender: Imagawa Yoshimoto

Receiver: Takeda Shingen

Date: 23rd day of the 9th month of Tenmon 10 (1541)

“Recently I planned to send a messenger to you to convey the following information, however considering that Sōinken will make a journey to Kōfu (seat of the Takeda family), I have asked him to relay the content of this letter to you.

It pleases me to know that a number of good days have been forecast for the 10th month, and that the women of Nobutora’s retinue will be able to journey here during that time. Let it be known that I wish to accommodate these women. It is my fervent wish to act in accordance with the Way of Heaven, if that is indeed possible.

In relation to the cost of Nobutora’ s upkeep, in the 6th month both Taigen Sessai Sūfu and Okabe Mino no Kami Sadatsuna visited Kōfu and I believe gained your understanding on this matter. It is gradually growing colder, and it pains me to think that Nobutora might be suffering from want. It is for this reason that I ask you to waste no time in informing me in detail the number of women I shall need to accommodate. Once I have this information, I shall explain its details to Nobutora in a manner that he will understand.

Further details will be provided by Sōinken.

Respectfully,

Yoshimoto (signature)” (16-17)

“Sōinken” refers to the priest Yui Ansei, who was an acolyte of the aristocratic scholar Reizei Tamekazu. To explain a little in relation to Sōinken, two years before this letter was sent (i.e., Tenmon 8), Sōinken had been invited by Shingen (then known as Harunobu) to visit Kōfu and participate in a poetry recital. In the 16th year of Tenmon Sōinken had travelled down to Suruga, and thereafter took the tonsure. While serving as both a teacher and acolyte, Sōinken acted as a go-between for the Takeda and Imagawa families. It was this “Sōinken” who arrived in Kōfu late in the 9th month carrying a letter from Imagawa Yoshimoto. The content of the letter was simply that Yoshimoto wished to know how many of Nobutora’s female companions he would have to play host to in Suruga.(17)

One particular interesting thing about this letter is its referral to the visit by Taigen Sessai, an important councillor of the Imagawa family. Sessai visited Kōfu during the 6th month, the same month in which Nobutora was concurrently on his way to Suruga. While in Kōfu, Sessai had gained Shingen’s approval for payments aimed at keeping Nobutora in comfort during his retirement. What this means is that the Imagawa already knew (from the 6th month onwards) that the then head of the Takeda household would not be returning to Kai. Hence it is plainly obvious that the plot to expel Nobutora from Kai was one hatched between Shingen and Imagawa Yoshimoto. (18)

When one examines the power relationships in place at the time, clearly it was Yoshimoto, together with Taigen Sessai, who raised the possibility of Shingen assuming the role of ruler over Kai. Yoshimoto had been instrumental in arranging Shingen’s marriage to a daughter of the Sanjō aristocratic family, while Shingen’s elder sister had been married off to Yoshimoto. It was Yoshimoto’s scheming that had allowed Shingen to assume the mantle of leader. In reality, Shingen got his start along the road to national unification under the auspices of the Imagawa family. The scenario often depicted in historical novels, in which “Nobutora, in deference to Shingen’s will, arrived in the territory of the Imagawa” is simply implausible and does not reflect the historical truth.(18)

Shingen was, in a sense, tied via an alliance to the Imagawa. In Tenmon 14 (1545), Shingen dispatched troops to assist Imagawa Yoshimoto, and in Tenmon 21 had his eldest son, Yoshinobu, married off to the daughter of Yoshimoto. At the very least, Shingen was in no position to betray Yoshimoto. If Yoshimoto hadn’t been killed at the hands of the Oda army during the Battle of Okehazama, the territorial map of the Kantō region would have looked very different to what it eventually became.(18)

If the situation had remained as it was, the Takeda would eventually have been swallowed up by the Imagawa. Shingen, well aware of this possibility, harboured very strong ambitions to increase the Takeda’s land holdings by whatever means he could. As such, Shingen’s first act upon becoming head of the household was to arrange an invasion of nearby Shinano province. The reason for doing so was simple – there were no powerful daimyo present in Shinano.(18)

At the time, the Suwa region of Shinano province was controlled by Suwa Yorishige, who was also the guardian of Suwa shrine. Shingen’s younger sister had been sent to Yorishige as a bride during the rule of Nobutora, who maintained an alliance with the Suwa. This had allowed the Suwa to become complacent. After declaring Yorishige to be an enemy of the Takeda, Shingen launched an attack on the Suwa territory, forced Yorishige to surrender, and then sent him under guard to Kōfu where he eventually committed suicide. Shingen then invaded the territory of Saku and attacked Shiga castle. After wiping out reinforcements sent to aid the castle, Shingen used some psychological warfare on the defenders, lining up some 3,000 heads of slain enemies around the perimeter of the castle to place pressure on those inside. Any defenders who tried to escape during this time were caught and killed, which eventually led to the castle’s surrender.(19)

Any men and women still left alive inside the castle were transported to Kōfu where they were sold off as slaves . A record of this time, the “Diary of Katsuyama (Katsuyama Ki)” describes the scene as thus;

去程二男女イケトリ被成候而、悉甲府へ引越申候、去程二、二貫・三貫・五貫・一貫ニテモ身類アル人ハ承ケ申候

“And so, both men and women were taken prisoner, whereupon they were hauled back to Kai province. Once there, relatives were sold off for two, three, five, nay sometimes not even for one kan in money.” (19)

One can imagine the situation at the time, with money being exchanged time and again for the merchandise on display. This was not an unusual scene, but was part of Shingen’s basic strategy. It was the end result of a world ruled by real politik and war. (20)

When one examines the “Kōshū Hattō no Shidai”, Shingen appears to be very much a realist when it came to financial matters. For example, the Hattō itself originally consisted of 26 laws, which were then expanded to 55, and then expanded again to 57. At first, priests were forbidden from having wives, yet this law was erased from later versions, and any priests who possessed wives had merely to pay a “wives’ tax” whereupon they would be permitted to continue their secular living arrangements. (20)

It was this realism combined with a desire for profit that led Shingen to wage war against neighbouring territories. Shingen was one of the first daimyō to introduce firearms into his armies. At the 2nd Battle of Kawanakajima (held in the 1st year of Kōji, or 1555), Shingen made use of a musket troop consisting of 300 soldiers. In strategy, as in many things, Shingen was at the forefront of his peers, and was no imitator of Oda Nobunaga.(20)

However, there was one major obstacle to his plan for territorial expansion. As you will have no doubt guessed, this was the arrival on the scene of Uesugi Kenshin. While Shingen was engaged in contests against Kenshin over the narrow plain of Kawanakajima, to the west Oda Nobunaga of Owari province made his presence known.(20) In the midst of this maelstrom, the Takeda household itself was shaken by a major incident. Shingen’s eldest son, Yoshinobu (who at the time was 28 years old), together with some of his close retainers Obu Toramasa, Sone Suō, and Nagasaka Gengorō, became involved in a conspiracy to assassinate Shingen (who was 45 at the time). (20)

Why had they chosen to do this? It appears that the Imagawa were once again involved. Ever since Tenbun 5 (1536), the Takeda had kept their pledge to the Imagawa not to invade the other’s lands. However Yoshimoto was dead, and his successor Ujizane appeared to be a plain, boring individual with few interests other than the game of Kemari (or kick ball). Given this state of affairs, Shingen planned to break his pledge to the Imagawa and invade their lands. However Shingen’s son, Yoshinobu, was married to the daughter of Imagawa Yoshimoto and was opposed to his father’s scheme. Yoshinobu then began to approach other like-minded retainers.(21)

In the background to Yoshinobu’s plan may have been an awareness of the fact that “Shingen himself only succeeded (in becoming head of the household) through the assistance of the Imagawa “. At any rate, the conspiracy was uncovered before it could be hatched. Toramasa was executed, while Yoshinobu was made to take the tonsure and enter the temple of Tōkōji in Kōfu. On the 19th day of the 10th month of Eiroku 10 (1567), he committed suicide at the temple.(21)

The death of Shingen’s eldest son allowed him to overcome the most serious threat to his position since coming to power. While he himself had conspired to exile his father, his son had conspired against him and lost. Shingen was nothing if not looking after number one – himself. As Shingen had come to power through a conspiracy launched with his retainers, it was inevitable that he would be concerned about the degree of loyalty his retainers had towards him. (21)

Just before Yoshinobu committed suicide, each retainer of the Takeda household submitted a “blood pledge” (or Keppan Tsuki Kishōmon) to the executive of the household. These were then gathered together and lodged at Ikushimataru Shrine in Chisagata gun, Kai province. The content of those blood pledges were as follows;

Shingen’s paranoia writ large

Letter Sender: Takeda Nobutoyo (retainer of the Takeda household)

Receiver: Yoshida Nobunari – Asari Nobutada (executive members of the Takeda household)

Date: 7th day of the 8th month of Eiroku 10 (1567)

“To all I respectfully wish to announce the following

Pledge

Item, I hereby submit that the oaths I am to take do not in any way differ to those I have made previously.

Item, I hereby pledge that I will harbour no plans of betrayal, conspiracy, nor revolt against Lord Shingen.

Item, I hereby pledge that even if I am tempted by enemy forces led by Nagao Kagetora (Uesugi Kenshin) or others, I shall not give in to such temptation.

Item, I hereby pledge that even if generals of the three provinces of Kai, Shinano, and western Kōzuke plan to betray their lord, I myself shall not waver in my loyalty to Lord Shingen, and will remain devoted in my duty to him.

Item, I hereby pledge that on the occasion of the invasion of Suruga and the mobilisation of forces to that end, I shall not harbour any doubts about our purpose, and am resolved to fulfil my military duties.

Item, even if other members of the household speak ill of the Lord of Kai and reveal themselves to be cowards, I hereby pledge that I shall never agree with them.

As above.

If I violate those pledges on the right, may I be subject to the divine punishment of the Brahman, of Sakra-Devanam-Indra, of the Four Protective Deities, of Enma the Lord of Hell, of the Demons of the Five Paths, together with the 132 gods of Kai Province, the gods of the land and bridges, the various manifestations of the Bodhisattva of the Mountains, of the Bodhisattva of Fuji Asama, of the gods of Upper and Lower Suwa, of Iizuna and Togakushi, of the Bodhisattva of the Three Temples of Kumano, Izu, and Hakone, of the gods of Mishima, the Bodhisattva of Hachiman, and the Great Deity of Tenman.

While I live may I contract leprosy, and in the next life may I be plunged into the bottomless pits of hell.

This, I hereby pledge.

7th day of the 8th month of Eiroku 10

Rokurō Jirō (Nobutoyo) (signature & blood thumbprint)

To Lord (Yoshida) Sakon no Suke

Lord Asari Uma no Suke” (22-23)

According to the “History of Kōfu City”, there are currently 83 such pledges in existence, which gives us some idea as to the substantial number of vows that Shingen collected from his retainers. It also reveals just how serious the “Heir’s revolt” was treated and how it shook the foundations of the household. In the aftermath of the attempted coup, it appears that the pledges were written in haste, as much to dispel any lingering doubt about the loyalties of retainers as it was to expedite the dispatch of troops for the invasion of Suruga. However it is difficult to conceive of these blood pledges having any effect on events that occurred during the reign of Shingen’s successor, Katsuyori.(24)

The final item of the pledge, which states that… “even if other members of the household speak ill of the Lord of Kai and reveal themselves to be cowards, I hereby pledge that I shall never agree with them” refers to the fact that when the lord of the household had decided upon war, there was nothing that the retainers could do to prevent this from occurring. It is also possible that any who insisted on a protracted struggle would be accused of cowardice. This may be one reason why the retainers of the Takeda at the Battle of Nagashino were unable to persuade Katsuyori to refrain from brazenly attacking the Oda-Tokugawa lines (which resulted in the total defeat of the Takeda army).(24)

After Yoshinobu’s death, Shingen quickly moved to break his alliances with both the Hōjō and the Imagawa, and in the 12th month of Eiroku 11 (1568) launched his invasion of Suruga.(25)

There have been a number of theories put forward as to why Shingen suddenly decided to invade Suruga. One is that he wanted access to the sea. Another states that he wanted to acquire Suruga’s supplies of salt. Yet another claims that Shingen sought control over the gold mines at Fuji Kaneyama and Umegashima. He may also have wanted to pacify the Tokaidō region in preparation for his march on the capital. Yet the main reason for the invasion was, in my opinion, the involvement of Oda Nobunaga. The evidence for this lies within the “Record of Time Spent At Hamamatsu Castle” (Hamamatsu Gozaijō Ki), which is as follows (25);

一、 同年、信玄ト大井川ヲ爲境、駿州ハ武田、遠州ハ權現様御切取被成候様ニト、國キリノ御約信御座候。

此取持ハ、信長公、甲州ヨリ、此使ニ山縣三郎兵衛賴實來ト申説御座候。

“In the same year (Eiroku 11), Takeda Shingen, placing the border at the river Ōi, made a pledge to divide up the (former Imagawa) territories with Tokugawa Ieyasu, with Suruga going to the Takeda, while Tōtōmi would go to the Tokugawa.

The intermediary in these negotiations was Oda Nobunaga, and I have heard that Yamagata Saburō Hyōe Yorizane was sent from Kai to Hamamatsu carrying the message of the pledge.” (25)

If one takes this diary entry at face value, it appears that Shingen expedited his invasion of Suruga on the advice of Nobunaga. Of course, Shingen was no fool, and he would have known that Nobunaga was planning to increase his own authority. By this time Nobunaga had finally succeeded in overthrowing Saitō Tatsuoki of Inabayama and gained control of Mino province. He had also given his support to the shōgun Ashikaga Yoshiaki and was in the process of planning to take the capital. In the meantime, having Shingen invade Suruga would ensure that he would not attack Oda’s territories while he concentrated on the capital.(26)

Eventually Shingen found himself in conflict against the Odawara Hōjō (who were allied to the Imagawa) and fought a series of small engagements against them. (26)

In the meantime there are some who believe that “Yoshinobu’s revolt” was a deliberate plot launched by Oda Nobunaga. Nobunaga, via Ieyasu, offered up the Imagawa lands of Suruga as an enticement to Shingen. Once Shingen had taken the bait, Nobunaga planned to provoke those retainers in the Takeda household who were friendly towards the Imagawa and thereby bring about discord within the Takeda. In the meantime Nobunaga himself would support the shōgun and acquire the authority of the highest offices in the land.(26)

As far as Shingen was concerned, it was very difficult for him to accept the successes of a rival that he considered to be his social inferior. Thereafter Shingen would find himself pressured by the combined forces of the Oda and Tokugawa, and so began searching around for possible alliances with the court, the religious complex of Ishiyama Honganji, Asakura Yoshikage, and the shōgun Ashikaga Yoshiaki in order to create an audacious strategy to contain Nobunaga. It certainly appears that an already aging Shingen and his strategy to expand his land holdings collided with those of Nobunaga, thus ending in a competition between the two for overall control. (27)

Yet by this time Shingen was already too late.

While possessing the will to destroy his eldest son and quash any internal dissent, inflict a devastating defeat on Tokugawa Ieyasu at the Battle of Mikatagahara, and finally face off against Oda Nobunaga, other daimyō began to act in ways that Shingen could not predict. The decision by Asakura Yoshikage to withdraw his forces from Ōmi province broke the ring of encirclement that Shingen had been building around Nobunaga’s territories. The day after Shingen forced Noda castle to capitulate (the 16th day of the 2nd month of Ganki 4, or 1573), he wrote a letter addressed to a retainer of the shōgun Ashikaga Yoshiaki. In the letter, Shingen’s annoyance at the Asakura’s behaviour is palpable.(27)

Shingen’s fury at the Asakura’s retreat

Letter Sender: Takeda Shingen

Letter Receiver: Tōkōken (a retainer of shōgun Ashikaga Yoshiaki)

Date: 16th day of the 2nd month of Ganki 4 (1573)

“I have received the letter that you sent to me, and fully comprehend its content.

However, I embarked on my journey from Tōtōmi after receiving encouragement from both Honganji and Asakura Yoshikage to do so. The fact that Honganji has been attacked by the forces of Nobunaga cannot, it seems, be helped. In spite of entering into an alliance with Yoshikage in order to attack Nobunaga, once Yoshikage withdrew from Ōmi and returned to his lands we lost any chance of victory.

Nevertheless, we still had some successes in the field, particularly the fall of Noda castle in Mikawa province. Thereafter we took the lord of the castle (Suganuma Sadamitsu) hostage, and sent him to Shinano. As for what happened thereafter I have heard a number of things from messengers, and do not have enough space on this paper to detail them all.

Do you think that fool Yoshikage should take to the field again? If anything, now is the time for him to accompany our armies.

Further details will be provided by Itasaka Kō Sessai (Shingen’s messenger).

Respectfully,

2nd month, 16th day

Shingen

To Tōkōken (28)

In the end, Yoshikage did not meet up with Shingen again. Shingen thereafter set off once again for the west. It was while he was on his way to the capital that he died at Komaba in Shinano province in the 4th month of the same year. Without a doubt, Shingen would have regretted not living longer.

Nonetheless, Shingen was an audacious leader and parent. The fact that he had his eldest son and those retainers close to him die, that he provoked the Hōjō, who were allied to the Imagawa, and that he made a temporary alliance with Oda Nobunaga only to turn around and declare Nobunaga to be his enemy after the destruction of the Imagawa, shows that he was nothing if not capable of adapting to circumstance.(29)

In order to seize the advantage, Shingen was prepared to sacrifice both his eldest son and future retainers (of course, the Kōyō Gunkan and other historical records portray this as occurring…“with tears in his eyes”). Incidentally, Shingen’s eldest daughter was married to Hōjō Ujimasa, however the breaking of the alliance between both families and the invasion of Suruga (since the Hōjō and Imagawa were also allies) meant that she was returned to Kōfu in Eiroku 11 (1568). In the following year, Shingen’s daughter, having lost consciousness, died at the relatively early age of 27. As a consequence of invading Suruga, Shingen lost both his eldest son and daughter.(29)

It is plainly evident that Shingen loved his children, particularly his eldest daughter, and wrote a prayer dedicated to her asking for the safe delivery of the child. The fact that Shingen could cause his daughter so much distress and harry his eldest son to kill himself for the sake of Shingen’s own territorial ambitions reveals just how typical his behaviour was as a general during the Sengoku era.(30)

However Shingen’s ambitions caused his successor, Katsuyori, an enormous amount of difficulties. Shingen, possible aware that life itself was short, began to become more desperate as time passed, and it does seem that this led in turn to the downfall of the Takeda household. It is for this reason that I think it is important to regard Shingen’s reputation as a “brilliant general” with a degree of scepticism.(30)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed