canberratimes.com.au

canberratimes.com.au De mortuis nil nisi bonum dicendum est.

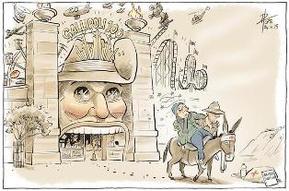

canberratimes.com.au canberratimes.com.au David Pope has brilliantly captured the mood of many Australians with this particular cartoon in this morning's Canberra Times newspaper. Let's just have quiet contemplation of the 100th anniversary of the Gallipoli landings, without the rampant commercialism and the ceaseless pontification of what it 'means' to the nation as though the rest of the war was of less importance. Gallipoli holds its own meaning for each and every individual - I note its significance, I acknowledge the sacrifices made, I stare in disbelief at the toll it took, and I mourn those we lost. De mortuis nil nisi bonum dicendum est.  Albert Gardiner Source: NLA Albert Gardiner Source: NLA This particular post will take a deviation from my usual observations on Japan to mark what will soon be the 100th anniversary of the Anzac landings at Gallipoli and Australia’s formal introduction to the industrialised warfare of the First World War. World War One defined much of what was to become Australian identity, and with good reason – from a total population of less than 5 million, Australia suffered 60,000 casualties. 420,000 Australians enlisted in the armed forces during the course of the War, representing 38.7% of the total male population. When this is compared with casualties, Australia suffered a casualty rate of 64.8%, itself one of the highest proportions of any country involved in the War (Source: AWM). With armistice called on November 11, 1918 and with the Paris Peace Conference underway in 1919, Australians would have felt justified in imposing on Germany and its allies a crippling level of debt in order to recoup its losses in manpower and materials. Yet not all Australians felt this way. One such Australian was a Senator in the federal Australian parliament from New South Wales, Albert “Jupp” Gardiner, a member of the Australian Labor Party and a former carpenter and gold miner. During a debate on war reparations in June of 1919, Gardiner made a number of comments which remarkable for the time in which they were made and for the sentiment that they express. Not one to unduly blame Germany for its actions, Gardiner instead issued a very level-headed, reasoned argument for leniency towards the former enemy by warning of the consequences of seeking revenge. What therefore follows is from the Commonwealth of Australia’s Hansard records for the Senate, dated Thursday, 26th of June 1919. “Senator GARDINER - It was a matter of circumstances, and now, in the calm light of peace, this comparison which I have instituted should be vividly kept in mind, particularly by those who were anxious that we should do more than we did. They used to taunt our party with Mr. Fisher's (Andrew Fisher, Prime Minister of Australia, September 1914 – October 1915) statement that we would stand by the Empire in this momentous struggle to the last man and the last shilling. I say that literally we adhered to the pledge. We stripped ourselves of our manhood to such an extent that we would have been powerless had we been attacked. So far as the last shilling is concerned, not only did we spend it, but we borrowed money upon which we shall have to pay an annual interest bill of from £20,000,000 to £30,000,000. I have gone to the trouble of putting these facts and figures before honourable senators because I think that they should be placed upon record. At the outbreak of the war it looked as if nothing could prevent the foe from winning. At that time Germany appeared to be a world conquering force, whose objective was domination… Now we are confronted with the Peace proposals, and I know that there will be much diversity of opinion as to what should be done. "The culprit must be punished," will be the thought that will instinctively rise to the mind of every man. If the culprit could be centred in one man or even in a number of individuals there is no doubt that civilization would insist upon their punishment. But an enduring peace cannot be obtained unless it is based upon justice. Without justice we shall be sowing the seeds of future discord. Of course it may be argued that no consideration should be extended to men who were guilty of the acts of which our enemy were guilty. But the people who will govern Germany and Austria in the future will not be those who created this war. When it is urged that they indorsed the war my reply is that the first duty of citizenship is to offer one's life if necessary in the defence of his country. In the hour of danger the first duty of a citizen is to fight for the country in which he lives. If we accept that maxim none of us can punish the German soldiery for fighting for their country. We may insist upon reparation being made for the wrong which has been done, but with sentiments like those in our hearts we cannot say that the men who answered the call in Germany were doing other than their duty to their own nation. These truths must be kept in mind in the peace that is now being forced upon the world whether by the strong arm of the military power or by wise counsels at the council table. I believe that Peace has been signed, and that the German people will, if they have agreed to certain proposals, carry them out. We have only to look back to the occasion when Germany conquered France in 1870 and 1871. I suppose that the most powerful German statesman at that time was Bismarck. Bismarck was forced by the pressure of public opinion in Germany to assent to an unjust peace, a peace that took much territory from France. He himself pointed out the dangers attendant on a peace that would leave France with a lasting grievance, and that, I believe, was one of the Teal causes of the present war. Probably that was the germ - a nation proud in arms as France was, being humiliated by cession of territory - that was responsible for this awful world conflict. Let us beware that history does not repeat itself. Let us beware that in the hour of out triumph, we do not seek to impose upon Germany an unjust peace that will leave a lasting grievance in the minds of the conquered (Source).” These sentiments were obviously not shared by many others, and the reparations imposed upon Germany by the allied powers have often been cited as one of the principal causes for the rise of National Socialism. Yet the fact that an Australian politician was prepared to argue that an unjust peace would lead to more conflict is evidence of a maturity in thinking that surpassed many of Gardiner’s contemporaries. He knew that those that started the war would not be burdened with the consequences of it, that future generations would have to assume that responsibility and, depending on the conditions imposed on Germany, that they might resent their treatment at the hands of the victors. Amid the great amount of literature and correspondence on Australia’s reaction to the First World War, Gardiner’s comments still strike me as some of the most honest and well considered of all of Australia’s political class at the time. They are a credit to the man that expressed them, and I hope that they might receive more recognition in this of all years. This short post has been inspired (or provoked) by recent events across the globe.

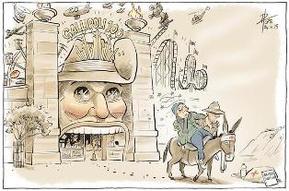

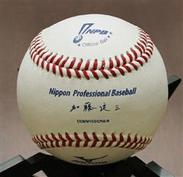

Are we fated to destroy ourselves? This is a question that no one person can answer. Over the passage of time humanity has behaved as though its future is predetermined, as though its actions do not have consequences that will influence how its future will unfold. Humans have seen fit to find fault with themselves, to prefer division rather than seek unity. Whether it be gender, age, nationality, or religion, if there exists a means for some to diverge from others, to promote self-interest, then that is the path that will be taken. Humanity as a species will not survive the next millennium without a collective effort to rescind that which divides us and embrace all. Our resources are not infinite, neither is the space that we occupy. We threaten our own existence through our parochial behaviour, and if we do not address this now then we will never will. The latent possibilities of humanity are obvious to any member of the species homo sapien, for humanity has transformed the environment, reduced distance to mere seconds, mapped the heavens and catalogued the elements from which it is made. Humanity has transcended time, looked into the face of oblivion and still found hope, and sought an existence beyond physical limitations. This capacity for invention, for compassion, and for organisation has served us well, but the future of humanity lies in its capacity for cooperation, in recognising that if we allow division to dictate our actions then our potential to evolve will be forever impeded. We are not condemned to such a future, we have the capacity within us to achieve a utopia that will define the character of humanity. But it will not be through the self-interest that we, all of us, currently pursue. We are all as great as our collective sum, and together we can find meaning to this thing called existence.  Source: www.yourepeat.com Source: www.yourepeat.com First of all, Happy New Year! During the end of year period there was a great deal of activity in Japan in preparation for 2015, including PM Abe’s address at Ise Shrine where he declared that he intended to issue another statement on the 70th anniversary of the end of WWII, and that this statement would be in keeping with those of previous PMs including Murayama Tomiichi, along with a later announcement of budgetary arrangements for 2015 that included the largest increase in defence spending in postwar Japan (for the third year in a row. This is mainly because of the need for purchases of the F-35, a new fleet of P-1 surveillance aircraft, amphibious vehicles, and preliminary construction of facilities at the designated US forces base at Henoko in northern Okinawa) (J). Yet despite these developments, I wanted to look at a more personal matter that I’ve been meaning to bring up for some time. It concerns the work of author Dōmon Fuyuji (otherwise known as Ōta Hisayuki), and the contribution I believe he has made to a better understanding of Japan’s past and the drama contained within it. I’d hazard a guess that Dōmon is not well known outside of Japanese historical circles, but his writings and essays do deserve a wider audience given the way in which he is able to present quite complicated historical events in clear, direct prose. My first contact with Dōmon occurred during my final years in university, when I was looking to find Japanese language material that would explain events in Japan’s past in language that I, a Japanese language novice, would still be able to understand (with a little help from a dictionary). I managed to obtain a copy of a reference book detailing the ‘business savvy’ of various Sengoku era generals edited by Dōmon. While the subject matter was fairly frivolous, Dōmon’s use of clear, modern prose, and his ability to illustrate a point that highlighted the human character of Sengoku generals, impressed so much that I vowed to look up more of his work when I had the chance. That chance came later while I was living in Japan. It was while I was there that I learned that Dōmon had begun his career as a bureaucrat in the Tokyo municipal government, eventually working his way up to speech writer and secretary to the governor. He was in his early 30s when turned his hand to writing historical novels, covering periods from the Kamakura era through to the Meiji Restoration. While other writers of historical novels, in order to increase the ‘historical credentials’ within, choose archaic terms and old linguistic forms to pad their text, Dōmon eschews the more ‘traditional’ approach to historical novels in order to promote the story itself. Purists might deride this as pandering, but the fact remains that it has made Dōmon famous, almost (but not quite) to the same level as Shiba Ryōtarō (a contemporary, incidentally, of Dōmon). Dōmon regularly features in NHK documentaries on historical figures of note, and his opinion is sought out by editors keen to get a sense of prominent figures of Japan’s past. I’m currently reading Dōmon’s novel of the life of Kuroda Kanbe’ei (Nyosui), which coincided (possibly not by coincidence) with an NHK Taiga drama on the very same individual. As per usual the writing is very straight-forward, and Dōmon obviously has a lot of admiration for his subject. He has previously described Kuroda as being one of the most brilliant strategists of the Sengoku era who never attained his true potential, and portrays Nyosui’s cunning against the more ‘honest’ character of Nyosui’s heir Nagamasa (‘honest’ being a very subjective term in relation to Nagamasa). In sum, Dōmon is well worth a read for those with Japanese language ability, and is certainly very useful for expanding one’s knowledge of historical characters. His exhaustive bibliography alone will consume many of my reading hours for years to come.  Source: narinari.com Source: narinari.com It has been interesting to read recently of the fallout (no pun intended) from the latest issue of ‘Oishinbo’, a long-running manga comic produced by Shogakukan in which the main protagonist, a gourmet by the name of Yamaoka Shirō, tours about Japan with his sidekick Kurita Yūko, tasting various local delicacies and learning something of the culinary traditions of Japan (and other nations) along the way. This month the intrepid two made their way to Fukushima Prefecture, the storyline of which included a visit to the Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant (as to why, ask the editors). In one of the frames of the comic, a character is depicted as having a nose bleed as a result of visiting the area around the power plant. In another frame, the former mayor of Futaba-chō, Idogawa Katsutaka, says that the nosebleed is because of exposure to radiation, adding that many people in the area have suffered nosebleeds and extreme lethargy, and warns that people should not live in Fukushima for the time being (J). For a prefecture still affected by the stigma related to its exposure to radiation from the Daiichi power plant, this depiction elicited a range of comments, mostly criticism of the ‘insensitivity’ of the editors of Shogakukan in illustrating Fukushima in such a negative way (a point of view stressed by the Fukushima prefectural government, who complained that no-one in the prefecture had suffered the type of illnesses depicted in the comic) (J). As an aside, the governments of Osaka City and Osaka Prefecture also objected to the depiction of people suffering from eye and breathing problems as a result of the radioactive waste transported from Fukushima for disposal in the Kansai region (J). Even the federal government got in on the act, with Parliamentary Deputy Environment Minister Ukishima Tomoko stating that it was ‘disappointing’ that Shogakukan had chosen to illustrate Fukushima in such a fashion, especially ‘when the people of Fukushima are doing their best (presumably to overcome the events of 3.11)’, and according to Environment Minister Ishihara Nobuteru, no link has been established between nosebleeds and exposure to radiation - (J) and (J). The author of the manga series, Kariya Tetsu (72), was reported in January this year as having suffered from a series of nosebleeds after visiting Fukushima Prefecture a number of times since 3.11 (these details were included in an interview with Kariya conducted by the Nichigo Press newspaper in Australia) (J). After the publishing of the controversial comic frames, Kariya directed anyone with claims against them to aim their criticism at him rather than Shogakukan, saying that the responsibility for the frames was his alone (J). It seems that much of the criticism being directed against both the comic and Kariya stems from a belief that without any scientific basis, Oshinbo has raised the spectre of radiation fallout in a country still coming to terms with the meaning of 3.11, and by doing so has created an unnecessary level of fear and apprehension concerning not only Fukushima Prefecture itself but what it represents – namely, a failure to cope with disaster. While recent months have seen moves towards re-starting nuclear power plants across the country despite widespread anguish at the degree of reliance on nuclear energy, the questions raised by Kariya have certainly sparked renewed debate about the consequences of nuclear accidents and whether the government (any government) can be trusted to deal with them properly. The degree of anger directed at Kariya and Shogakukan suggests that the debate about nuclear power in Japan is a long way from being resolved, and that the anguish of Fukushima still weighs heavily upon the psyche of the nation.  Source: huffingtonpost.co.jp Source: huffingtonpost.co.jp This particular post takes as its subject the case of stem cell researcher Obokata Haruko, and the entire frenzy of claim, counter-claim and sensationalism that has surrounded her since the announcement on January 29th this year that her team at the Riken Centre for Development Biology (based in Kobe) had successfully managed to create STAP (stimulus triggered acquisition of pluripotency) cells using an acid based stimulation technique. The news itself was heralded as a breakthrough in cell research, with expectations that it could eventually lead to the development of tissue technologies to combat illnesses such as diabetes, Parkinson’s disease, among others. For such a young researcher (Obokata is a mere 30 years old, a doctoral graduate of Waseda University and postgraduate student at Harvard University under the direction of Professor Charles Vacanti), her results were certainly unique, if not exceptional. This is where problems began to emerge, and in order to explain it in depth a little background is necessary. In March of 2011, Obokata submitted her doctoral thesis for review by Waseda Professors Tsuneda Satoshi and Takeoka Shinji, along with Dr Yamato Masayuki of Tokyo Women’s Medical University and Professor Vacanti (although Professor Vacanti later revealed that he had received a copy of the thesis, but had not been asked to review it). The thesis was accepted by all three (sic) reviewers, and Obokata obtained her doctorate. After completing postgraduate work Obokata was forced to remain in Japan after the Great East Japan Earthquake and continue her research under the direction of Riken (which she joined in 2011). Obokata, whose youth, combined with her love for the fictional Moomin characters and penchant for stylish dressing set her apart from other researchers, secured her own research prep laboratory (painted pink and yellow - video) and continued her work on stem cell manipulation until January 30, when the results of this research were published in Volume 505 of Nature magazine. Obokata’s claims in her Nature article, combined with the fact that pluripotency had been tried by numerous researchers across the globe for decades without success, did raise suspicions about the validity of Obokata’s research. These suspicions grew during February, when the Asahi Shimbun and other domestic newspapers reported that research photographs accompanying Obokata’s doctoral thesis bore an uncanny resemblance to those pasted on the American National Institute of Health website under the title of “Stem Cell Basics” (J). This led Professor Takeoka to once again review Obokata’s thesis, during the course of which it became clear that other photographs in Obokata’s thesis were identical to those on the Cosmo Bio Company website. Cosmo Bio claimed that the photographs in question were taken in 2007, long before Obokata submitted her thesis, and that the photographs had never been offered to Obokata (J). Given these revelations, on the 17th of February Riken, under the direction of Riken’s chairman Professor Noyori Yōji, held a press conference to announce that it would conduct its own investigation into Obokata’s research on STAP cells (J). The investigation found that Figure 1i (detailing DNA sequences) in the Nature article had been manipulated, and that Figures 2d and 2e in the article had been taken from Obokata’s doctoral thesis. Professor Noyori claimed that Obokata had been careless with the data she had accumulated, that Obokata had acted alone when manipulating the data, and that she lacked a sense of responsibility (J). Riken’s research chief, Professor Takeichi Masatoshi, said that the article had been poorly constructed (literally ‘it’s not a thesis’), while the researchers in charge of overseeing Obokata’s work, Sasai Yoshiki, Wakayama Teruhiko, and Tamba Hitoshi, all of whom who worked with Obokata on the article, bore a ‘grave responsibility’ for what had occurred. Obokata continued to claim her innocence of any malicious intent when submitting the article, saying that no-one had told her that modifying photographs was illegal and that her team had merely wanted to display the best pictures for review. She also claimed that she had discovered the irregularities in the article before it was submitted to Nature magazine and consulted with Nature on these points. Despite calls for her to rescind her findings and for the article to be removed from Nature magazine, Obokata protested that her research was valid, that STAP cells could be manufactured, and that the undue pressure being placed on her by her employer and the media was affecting her health (J). After spending some time in hospital, on the 8th of April Obokata gave another press conference at a hotel in Osaka (J), where she admitted that her inexperience and carelessness had contributed to the situation she now found herself in. Nevertheless, she again repeated her objection to the findings of the Riken committee (a position she took when it released its report on the 1st of April), and pledged to continue to seek verifiable, conclusive evidence for the creation of STAP cells. Media commentators (and academics such as Robert Geller of the University of Tokyo) have raised questions about the method in which Riken sought to hang Obokata out to dry. It does seem somewhat implausible for a scientific research organisation to appoint three experienced researchers to oversee Obokata’s work, only to slam both them and Obokata for poor research methods. Would it be too farfetched to suggest that Riken expedited Obokata’s research before it was completed, on the belief that it would then generate sufficient interest in Riken’s activities and the financial benefits that would invite? For so many experienced biologists to submit an article to Nature magazine, itself a widely respected academic journal, using falsified data is very difficult to accept at face value. While Obokata may have been naïve, she has not deserved the storm of criticism flung in her direction by those who believe they have somehow been ‘duped’ by her initial press conference in January. The announcement was an institution-wide event, and not of Obokata’s own doing. There is far more to this story than has yet been brought to light.  Source: jijipress.com Source: jijipress.com The 11th of March, 2011 was an ordinary day for an embassy employee such as myself, and I dare say for many others. After following news reports on the activities of the Gillard government throughout the afternoon, both myself and my colleagues were looking forward to the long weekend that was about to come and the opportunity to find some relief from the media cycle. While seated at my desk and with barely 15 minutes to go on the clock, a diplomatic staff member suddenly entered the room saying that there had been a serious earthquake in Japan, and that there were real fears of a tsunami. Not having access to a television I and my colleagues made our way to one of the monitors tuned to NHK which was broadcasting live footage of the Tōhoku region. At first I thought that I was looking at fields covered in snow, before closer examination revealed that the entire coastline was covered in water and that water was pushing ever further inland. Soon an NHK helicopter brought closer footage of the progress of a huge black wave, devouring anything and everything in its path – houses, fields, cars, roads, everything. Having never seen such footage before I was at a loss as to how to react to it, but it was obvious that this was no ordinary event and the consequences of it would be dire. While the diplomatic staff at the embassy stayed at their posts to liaise with their Australian counterparts, I returned home and spent the remainder of the evening both watching footage from the BBC and CNN of the unfolding disaster, and Skyping and emailing friends in Japan to see how they were and whether they were all safe. It was while I was watching such footage that the events at the Fukushima nuclear power plant began to spiral out of control, and that with every passing hour the fear that the entire facility could suffer a catastrophic meltdown grew in all of its terrible anticipation. During that time I compiled as much information as I could on what was happening in Japan and how the world was reacting to it. This was a process that I kept up for the next three days, glued to my computer monitor and the television screen in front of me, hoping against hope that Fukushima would not fall victim to a horrific fate. As time passed and the scope of the disaster became more apparent, I resolved to do what I could for Japan in its hour of need, signing onto the Red Cross to make an initial donation in the hundreds of dollars and fixed donations every month thereafter. I felt a sense of pride in my nation, Australia, as it offered the unconditional use of its disaster response team and dispatched transport aircraft of the RAAF to assist in the transport of people and supplies to and from the disaster affected regions. Given the degree of closeness that Japan and Australia had forged over the past twenty to thirty years, here was the physical evidence of that friendship. Not only this, for despite Australia having experienced a summer punctuated with natural disasters of its own, namely flooding in the southern Queensland and northern New South Wales border area and northern Victoria, Australians were still moved to donate hundreds of thousands of dollars to the relief effort underway in Japan. While this was occurring, the threat posed by Fukushima to the safety of all residents in the Tōhoku and the Kantō regions escalated with the explosion of the second reactor, an event that had Tepco (Tōden) contemplate the evacuation of the facility and all of its personnel until this was halted by a directive from the prime minister’s office. Even at this distance, there was a real belief that the government of Japan had lost control of the Dai-ichi power plant and that the full extent of radiation leaking from the plant was not being accurately or honestly conveyed. As news bulletins carried pictures of the second reactor explosion and of masses of people seeking to leave Japan via Narita airport (which led to the creation of the pejorative term ‘Fly-jin’ to describe foreigners fleeing the country), world governments continued to press the Japanese government for detailed updates on events both at Fukushima and further north, with European governments in particular issuing warnings to their citizens to remain well outside the perimeters set by the Japanese government and to evacuate Japan at the first available opportunity. To its credit, the Australian government did not follow this route, instead advising its citizens to avoid any unnecessary travel to the Tōhoku region but to remain in contact with the embassy in Tokyo and monitor news updates. Not a few weeks after the disaster, Australia took a more active approach in displaying its solidarity with Japan through the visit of then PM Julia Gillard to the town of Minami Sanriku in Miyagi prefecture. This was heralded as the first official visit to the disaster area by a foreign head of state (French President Nicholas Sarkozy had diverted his schedule at the time to be the first to visit Tokyo and speak with then PM Kan Naoto, although this was not officially sanctioned). While Gillard had been the subject of much criticism in Australia for the manner of her coming to power, her visit was an edifying moment. It showed a regional leader prepared to risk her personal safety in order to assure the people of Japan that they were not alone and that Australia stood by them. For all the faults that Gillard had, one could say that this was a prime example of statesmanship, and one for which she should receive ample recognition. In August of 2011 I journeyed to Japan myself, undertaking a two week visit of the country that would take me from Kyushu all the way up to Hokkaido. While I was in Japan I paid a number of visits to bookstores across the country, and found the volume of material voicing criticism of the government response to the disaster in March to be quite surprising. The most common theme running through each magazine article and book describing the events of 3.11 was the complete disregard shown by Tōden for the people of eastern Japan, how Tōden had prevaricated and obfuscated its response to the disaster, how it had ignored recommendations to increase the wave walls at Fukushima Dai-ichi or install back-up infrastructure separated from the coastline (which led to criticism of the Ministry of Infrastructure for not enforcing stricter regulations regarding the operation of nuclear facilities). There was real anger in those materials, at how government and industry had conspired at the expense of safety, how profit seeking had overridden any concern about building nuclear power plants in a country so prone to earthquakes and other natural disasters, and how Tōden seemed answerable to no-one, not even the government. With the passing of the years, the Tōhoku region has slowly followed along the path of progress, although that path has often been hampered by funding concerns and a lack of urgency from government agencies responsible for recovery. It is true that large parts of the coastline of the Tōhoku region remain uninhabited and may never again be so, not while the threat of another such event looms large in the memories of its residents. 3.11 was an event of such trauma and on such a scale that communities up and down the Pacific side of the Japanese coast have built countless monuments both to the victims and warnings to future generations, reminding them that the horrors of 3.11 could again be repeated without continued vigilance, and that the ghosts of those taken might remain unmourned amid the empty ruins along the shore.  Source: ///sankei.msn.jp.com Source: ///sankei.msn.jp.com I’m going to permit myself to indulge in a bit of non sequitur posting this week, and instead of bringing attention to the latest in the continuing debate on the merits (or lack thereof) of Abenomics or polling ahead of the House of Councillors election, I am going to look at baseball – specifically the issue that arose earlier in the week regarding the balls currently used by Japan’s baseball league and overseen by the Nippon Professional Baseball Association. On Tuesday Commissioner Kato Ryozo, when speaking to the Player’s Association (but not team managers or owners), revealed that the balls that had been used in games since the beginning of the season in April (and manufactured by Mizuno) were not to standard and had a higher degree of resistance when hit (meaning that they travel further, sometimes up to a metre beyond previous measurements) (J). This news did not come as a great surprise to either fans or the players themselves, who noticed since the start of the season that the number of home runs being hit far outstripped those of the previous two seasons when regulations for more ‘pliant’ balls were introduced to prevent teams from indulging in home run derbies (J). What has made this case so special is that until Tuesday the NPB had been telling fans and the media that there were no differences between the balls used this year and those from last year. In order to justify the increase in homers, coaches put it down to a smaller strike zone, meaning that pitchers who had gotten used to a larger strike zone as a result of the introduction of the ‘3 and a half hour rule’ (to end games early in case of shortages in electricity) were making it easier for batters to belt the ball all over the field by pitching to areas now outside the strike zone. Needless to say, the revelation from the Commissioner himself that this wasn’t the case at all didn’t go down too well with either players or fans, who swamped the NPB homepage with complaints (around 4000 by Thursday, according to the Sankei Shimbun)(J). It, of course, has raised questions as to why the NPB did not address concerns early in the season and conducts tests to ensure that the balls were standard, with some claiming that the NPB allowed the balls to be used to draw in fans, thereby boosting ticket sales (a claim the NPB denies). It also raises questions regarding the number of home runs scored so far this year, and whether the number of home runs an individual player has scored so far this year should be eliminated from their professional record (“Sorry Matt Murton – that homer at Koshien on April 30 giving Hanshin the lead over Hiroshima was rigged”). If there are any winners from this state of affairs, they are most definitely the pitchers of various teams who have had to grin and bear it as yet more and more of their pitches sailed over outfield fences. Some might have even begun to doubt their throwing abilities, and with it their livelihoods as professional league pitchers. While home runs are all well and good as part of the game, they shouldn’t be held up as the only method of scoring, as they are, and no offence to batters, the ‘dumbest’ (or most certain, depending on your point of view) form of run scoring available in the game of baseball. Hitting short infield bouncers, or ‘Texas leaguers’, and then using a combination of steals and base running ensures a more exciting, dare I say, a more strategic form of baseball than just ‘swinging for the fences’ and hoping for the best. Ultimately the NPB will offer its apologies and life will move on, but its silence in the face of mounting evidence of use of non-regulation balls will affect its image, and with it the reputation of Japanese baseball for fairness. So far Association Chief Shimoda Kunio has offered his resignation, although no word on whether Commissioner Kato will follow suit. Given that this involves Japanese teams, resignations are considered the most appropriate means of making amends for mistakes (with reinstatement coming some time afterwards). If Commissioner Kato remains where he is, the level of complaints against the NPB will merely escalate and may impact on revenue from games. If that happens, Kato will be shown the door, but the damage will already have been done, as Darvish Yu (currently with the Texas Rangers) fears in this piece. Not good, NPB, not good.  On Wednesday last week I had the privilege (of sorts) to attend a community consultation meeting at the Australian National University on measures to help implement the aims of the “Australia in the Asian Century” white paper launched by the Gillard government in October last year. The purpose of this meeting, so we were told, was to give ideas to the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) on the best means of reaching goals related to Asian literacy by 2025. What the meeting turned into, however, was a one and a half hour complaints festival primarily about the lack of funding for language education, and how the white paper had not recognised the contribution of migrants to improving Australia’s Asian education. As much as I support the ideas behind the white paper, I must say that community consultation meetings do not achieve much by way of results, mainly because of a trait among Australians (and possibly shared by those in other countries) to criticise and downplay initiatives before they have an opportunity to be heard or explored. As criticisms overwhelm enthusiasm for new projects, those projects are never explored, and the plans for them end up gathering dust on a shelf. It is an entirely frustrating experience to hear initiatives shot down again and again because they are “too expensive, too difficult, lacking detail, too detailed, too broad, too narrow, too exclusive, too inclusive” or just plain “unnecessary”. Given this state of affairs, it seems clear that the aims of the white paper will not be realised in the time frame given. What the white paper is proposing is essentially the entire transformation of Australia’s ethnic and cultural identity, asking a predominantly Anglo-Saxon, Eurocentric, English-speaking population to embrace Asia in order to secure its future. As a majority of Australia’s history has been marked by a distinct aversion to forging closer ties with Asia, to overturn decades (if not centuries) of traditions founded upon Christianity, Roman and English law, European and American history and the dominant nature of English is asking a lot of the Australian population, all the more so when it appears that the government is not prepared to provide the resources to make its ambitions a reality. A brief examination of mass media outlets in Australia does not give one hope that Australia is about to embark upon a radical transformation of its character. Commercial networks in Australia broadcast exclusively in English and show content that is overwhelmingly Anglo-American. The national broadcaster the ABC follows suit, with any ‘ethnic’ broadcasts confined to SBS, and even these are becoming fewer and far between (mostly 30 minute broadcasts of news bulletins from around the world in native languages throughout the morning). The nation’s newspapers, those that have a readership of half a million or more, are in English. A majority of radio broadcasts (except for those made by SBS and community radio stations) are in English. Most websites and blogs (including this one) are in English. To diversify this level of linguistic domination will take a considerable degree of investment from the government of the day, however the fixation of the Labor government on trying to bring the federal budget back to surplus (a Sisyphean task, it turns out) means that the funding isn’t there to achieve the goals of a foreign language revolution in Australian society. It all smacks of political expediency, especially considering the fact that there will be a federal election in Australia on September 14, and all predictions are that the current Labor government will be swept out of power. As the Coalition opposition have not given their support to the Asian Century white paper (as they hold their own policies towards Asia, which mostly involve boosting the number of students learning Asian languages – a partial solution to a much broader issue – an enacting a `new Colombo plan` to send thousands of Australian students to countries in Asia to absorb the languages and cultures of the region), it seems that the Australia in the Asian Century white paper is doomed to disappear with the government come September. It may still be referred to by committees on language education, or foreign affairs, but its usefulness will be limited. The white paper will also be used to gauge just how overly optimistic the Gillard government was about regional security issues, and the idea that economic concerns would trump any lingering animosity between states over access to resources and territorial claims. Examples of resource sharing between Malaysia and Thailand have been spruiked by Foreign Minister Carr as proof that nations can put aside differences and pursue common goals, but only when the resources in question do not intertwine with territorial demands and there are no lingering concerns stemming from history. In the case of Asia such examples are rare, and it is optimistic to the point of negligence to expect this to become the status quo in the current regional climate. While the Asian Century white paper has value in addressing the potential of Asia for Australia`s development, it is too focused on economic needs, does not address what the current state of Asian literacy is in Australia, doesn`t provide a plan or budget for reaching its goals, and so doesn`t offer any practical means of changing the monolingual, Euro-centred culture that defines modern Australian society. A society is a product of its past and present. Changing it for the future requires a considerable degree of forethought and investment which transcend political goals and short term gains. Only a government that has the ability for long term planning and a willingness to provide funding for its plans will create the change that both sides of politics recognise is important for the nation. It won`t happen under the current government, and it is unlikely to occur under its successor, either.  Source: Jomo Shimbun Source: Jomo Shimbun It is an often noted phenomenon in politics that when a government wishes to divert attention from its motives, it bestows an award upon a public figure of note. In Japan in recent years, this practice has proven beneficial to any administration wishing to focus the attention of the masses away from any contentious issue, or to place emphasis on the government’s magnanimity in recognising the achievements of the public figure beloved by the people at large. For example, following criticism of the manner the DPJ government had handled the nuclear crisis at the Fukushima Daiichi power plant, the victory of the Japanese women’s soccer team (“Nadeshiko Japan”) in the Women’s World Cup in August 2011 presented an ideal opportunity to bestow on the team a “People’s Honour Award” (or 国民栄誉賞, despite the fact that such awards had never before been granted to an entire team, and were meant to acknowledge numerous achievements over a lifetime, not a one-off victory). By ostensibly awarding an honour to “encourage the people” following the March disaster of that year, the DPJ managed to divert attention from the fact that an investigative team from the IAEA had found radiation levels around the No.1 and No.2 reactors at the Daiichi plant at 10 sieverts during the same week (by way of contrast, according to the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP), an acceptable level of artificial irradiation is 1 micro sievert per annum. 10 sieverts is the equivalent of 10,000 micro sieverts) (上杉隆、国家の恥:一億総洗脳化の真実、ビジネス社、東京、2012年, pp.88-89). Considering the nature of these awards, and the fact that they can be bestowed by the government at its leisure to any Japanese citizen, the timing of the announcement of such awards and their intended recipients has become as much a talking point as the award itself. The announcement on Wednesday this week (Link – J) that former Yomiuri Giants players Nagashima Shigeo and Matsui Hideki would be granted such an honour provoked speculation regarding just why the Abe government had chosen now to make the announcement, less than six months out from the House of Councillors election, and why it had chosen Nagashima and Matsui in particular. Asakawa Hirotada (Link-J) was one of the first to wade into the debate, noting that Nagashima (77 years of age) was of the same age as a majority of Japan’s pensioners, who would have fond memories of Nagashima during his playing days (and who make up a majority of the voting base in Japan). As for Matsui, although he has only just retired aged 38, his record with the New York Yankees (including a World Series championship) has been lauded in Japan, particularly among fans of the Yomiuri Giants (who have the largest following among all teams in the Pacific and Central leagues Link- J p.6). Although it seems entirely cynical to suggest that the Abe government is seeking to capture a majority of the vote in the upper house using populist methods, this appears precisely what Abe had in mind in choosing two prominent figures that appeal to a majority of voters before the upper house election (note the 35-70 age bracket and the increase in voter participation among such demographics here – p.8). As an aside, the Sankei Shimbun also reported on the curious manner in which the media got hold of the news of the announcement of Nagashima’s selection for an award (Link – J). Rather than it being reported by the Yomiuri Shimbun (owner of the Giants baseball club, and whom you would expect to obtain such a scoop), that distinction went to the local Gunma prefectural newspaper the Jomo Shimbun, which broke the news on Monday before any major papers (Link-J). What makes this even more curious is that Nagashima is not from Gunma prefecture, therefore leading to speculation that the news was leaked to the Jomo Shimbun by someone within the Abe Cabinet with ties to Gunma. So far, the most likely culprit appears to be Minister for Okinawan and Northern Territories Issues Yamamoto Ichita, a Gunma-ite through and through. Though Yamamoto protested his innocence (Link-J), the circumstances that led to the Jomo Shimbun reporting on the decision appear too unusual to rule out a leak. A regional paper scooping a nationally syndicated paper (with direct ties to the person being honoured)? Once in a blue moon perhaps, but the fact that the Jomo Shimbun didn’t note any particular access to inside information or sources makes the whole situation very odd indeed. Of course, none of this is to detract from the award itself or its recipients, who certainly deserve recognition of their achievements. When the award process becomes politicised, however, it reflects badly on the selection process and the motives of the government. Perhaps Asakawa is right in suggesting the creation of legislation that would ban the issuing of such awards six months out from any sort of federal election. |

AuthorThis is a blog maintained by Greg Pampling in order to complement his webpage, Pre-Modern Japanese Resources. All posts are attributable to Mr Pampling alone, and reflect his personal opinion on various aspects of Japanese history and politics (among other things). Categories

All

Archives

November 2023

|

|