Source: headlines.yahoo.co.jp

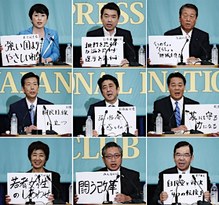

Source: headlines.yahoo.co.jp This was hardly going to be a riveting debate, and it became even more of a one-sided argument when in response to PM Abe’s taunt as to what the DPJ planned to do the invigorate the economy, representative Kaeida could only point towards a ‘healthy’ expansion in consumption and sustainability as necessary for economic growth (no reforms then, Ban?). Given the fact that the DPJ were in power in the Lower House until December last year, the fact that they could emphasise a need for a ‘bureaucratic review’ seemed an empty promise, one meant to garner attention rather than seriously propose a reform process for the bureaucracy. Things didn’t get any better for the Socialist, Communist, and People’s Lives First platforms either – they could all be summed up as opposition to joining the TPP, opposition to US bases in Okinawa (a standard view of the Communists and Socialists), and opposition to increases in consumption tax.

The Reform Party mentioned its pet projects of Diet reform (the creation of a single parliament by eliminating the Upper House), public election of the PM, and re-distribution of legislative authority to regional governments, while the Everyone’s Party decided to follow its particular bugbear of reducing the overall number of parliamentary representatives. In spite of the format of the discussion, clearly most of the questions asked were aimed at PM Abe, who wasted no time in stating the LDP’s position and criticising those of his opponents. This appeared somewhat unfair, and People’s Lives First representative Ozawa Ichiro said as much when questions about his former membership to the LDP and DPJ were raised by the media, with no questions aimed at the People’s Lives First policies(J).

Clearly this election is very much focused on PM Abe and his plans for the Upper House, almost to the exclusion of any other issue. As PM Abe himself stated during a press conference on the final day of Parliament’s sitting (June 26th), the current Parliament halted the passage of ‘vital laws’ such as energy reform legislation, benefits legislation, the formation of a Japanese NSC, and legislation dealing with the redistribution of electoral districts (the 0-5 plan)(J), hence a ‘twisted parliament’ was “the difference between a government that can achieve things, versus a government that is stifled in its aims”. As PM Abe still enjoys voter support levels in excess of 50% (J), the expectation of the electorate is that the LDP/Komeito Coalition will gain a majority of seats in the Upper House (at present there are 242 seats in the Upper House. As a majority requires 122 seats, and considering that the LDP and Komeito already hold 59 seats that aren’t up for re-election, the LDP/Komeito must capture 63 seats to ensure a majority, or 70 seats to secure a comfortable majority) (J).

As an aside, it should be noted that in order to change the 96 articles of the Japanese Constitution, PM Abe would require a 2/3rds majority or more in both the Lower and Upper Houses (J). While the LDP, Komeito, Reform Party and Everyone’s Party hold a ¾ majority in the Lower House, the Upper House is an entirely different prospect. While Abe may gain a majority in the Upper House, whether this extends to 162 seats will depend on just how much the voting public is in favour of constitutional revision.

This then raises questions of what PM Abe actually intends to do with his newfound ability to control both Houses. According to Professor Nakano Koichi of Sophia University (interviewed by the Australian’s Rick Wallace for its Saturday edition), Abe will probably use his authority to reform the education system (as was outlined in his 2007 book “Towards a Beautiful Japan”), seeking to increase the amount of positive messages on Japan’s achievements and reduce the previous focus on Japan’s culpability for deeds committed by its former Imperial forces. This issue is part of a larger narrative (explored earlier in this blog) on what PM Abe intends to do in relation to bilateral relations with neighbouring countries, and whether his government intends on repealing or re-writing the Kōnō and Murayama statements to bring them more into line with what PM Abe has described as ‘correct’ historical interpretation (E).

This type of rhetoric has the region worried, not least of which Australia. Such is the concern that Japan is about to re-write its position on the issue of war responsibility that Australian Defence Minister Stephen Smith, during a visit to Tokyo last week, felt it necessary to mention to Defence Minister Onodera and Chief Cabinet Secretary Suga that it is in no-one’s interests for either statement to be re-written, and that any move to do so could only worsen relations between Japan and its immediate neighbours (E). Whether this results in any reflection on the part of the Japan is debatable, however given that the US has also voiced its concerns, this may have some bearing on how the Abe government approaches issues of historical responsibility should it gain control of both Houses.

Not that Japan will be in too keen a mood to listen to the Australian government at present. The proceedings within the ICJ concerning Australia’s case against Japan’s whaling program (which is referred to in the Australia media exclusively as ‘so-called scientific program’) have led to some fairly sharp rhetoric and accusations of insult and duplicity. Attorney General Mark Dreyfus’ ire was particularly raised by the accusations levelled at Australia by Japan’s legal representative Professor Payam Akhavan, who claimed that Australia was engaged in a moral crusade and cultural imperialism, that Australia was somehow colluding with Sea Shepherd and attempting to turn the IWC into an anti-whaling body (E).

The strategy being adopted by Japan’s lawyers appears to be to demonstrate that Australia is bringing the case to the ICJ for emotional, not scientific, reasons, that the Australian argument is driven by the ‘prejudices’ of the Australian electorate, and that this should be no basis for debating whether the JARPA II program is scientific or not. Australia has retorted by saying that it has not referred to any cultural or moral arguments, and is merely seeking to prove that Japan’s scientific program is not in fact science but commercial whaling by other means, which is a violation of the moratorium on whaling (enacted in 1986).

The whaling issue itself has received extensive coverage in Australia (courtesy of the ABC, the Fairfax media, and the News Ltd media), and has gained some exposure in Japan where it has garnered the interest of newspapers (the Yomiuri Shimbun covered it here- J and here - J, the Mainichi Shimbun here - J and here- J, the Asahi Shimbun here - J ) but limited coverage on television (a quick examination of the internet only brought up hits for FNN, NHK (no video available) and TBS). Accusations of collusion between the Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry and the whaling industry have also clouded the issue, with Australia stating that Japan merely uses the issuing of scientific licences by MAFF to whaling companies as a cover for commercial whaling.

As Japan will give its verbal retort to Australia (and New Zealand’s) accusations in the ICJ next week, the issue will continue to cause some friction between all three countries, although Attorney General Dreyfus did clarify his statements in the ICJ by pointing out the otherwise good relations between Australia and Japan.

At any rate, Australia will be watching the progress of the Upper House election with some interest, with expectations that a win for PM Abe might finally lead to the third arrow of Abenomics being released (as newly appointed Treasurer Chris Bowen made clear to the AFR during an interview held last week - the article is here, although being the AFR, it is behind a firewall). With Australia set to go to the polls at some point before November 30, any sign that Japan may finally engage in market restructuring and put its signature to an economic agreement with Australia would be welcome news for the incumbent Labor government, and one it might be able to capitalise on to swing the rural vote in its direction.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed