Source:blog.webpage3.yahoo.co.jp

Source:blog.webpage3.yahoo.co.jp For our modern `rule of law` society, this state of affairs appears similar to anarchy, yet these multiple legal precedents had a much greater weighting in society at the time than the more formally established laws – indeed this was significant characteristic of the age. That it to say, in medieval society the `law` held varying degrees of value and could be manipulated to either exacerbate or relieve a situation. The more formally codified public laws were no more than one part of the `varying degrees of value` given to `the law`. (p.40)

The ethos that justified `katakiuchi` can be thought of as another of the legal mores of the age. Formally codified public laws were created by the people of society at the time, and thus legal precedents and traditions (such as katakiuchi) could have an enormous impact on society. As we saw earlier, one of the largest mistakes made by legal histories of katakiuchi in the post-war period (which explained that such practices were illegal) is that they tended to overlook the significance of precedents and traditions. Although the publically codified laws of the time might have banned katakiuchi, this does not prove that katakiuchi was considered to be an illegal act by medieval society.(p.40)

For example, the scholar Katsumata Shizuo analysed a social phenomenon similar to katakiuchi known as `megatakiuchi` (女敵討, or `killing a marital interloper`). `Megataki` (which could also be written as 妻敵) referred to a man (other than oneself) who slept with one`s wife, hence megatakiuchi was the practice whereby a husband would kill the other man out of revenge. According to Katsumata`s research, section one of Article 34 of the Goseibai Shikimoku from the Kamakura period bans the practice of megatakiuchi. Yet in medieval society at the time the practice of megatakiuchi was widespread, and there did not appear to be any awareness among those engaging in megatakiuchi that what they were doing was illegal. Rather the stance of the Kamakura Bakufu, by trying to make such a practice illegal, was itself regarded as `abnormal`. Hence Article 34 of the Goseibai Shikimoku really did not have any meaning, at least not for Kamakura era society. As proof of this, the practice of megatakiuchi actually escalated throughout the Muromachi period, and in the regional laws of Sengoku era daimyō was one of the practices sanctioned under the law and was codified. One could call it a typical example of the more formal public `law` and common `law` combining their strengths.(p.41)

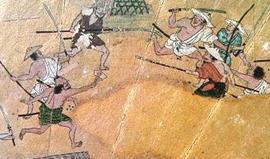

From the 1980s onward in medieval Japanese research circles, the self-governing practices of the common folk in villages and towns became a focal point of study. The existence of group acts of vengeance by villages and towns became widely known. As the results of studies by Fujiki Hisashi demonstrated, in the territorial disputes carried out between villages known as sōron there were various legal precedents for both issuing challenges and conceding defeat. Thus despite the violence of the times society still recognised the legitimacy of certain acts. Although medieval Japanese history research has only recently shed light on these phenomena, what is certain is that medieval Japanese society itself did sanction the practice of revenge.(p.41)

To try to recover one`s honour or goods without recourse to public law is known by the historical legal term of `jiriki kyūsai` (or `self-preservation`). Medieval Japanese society did not necessarily regard such practices with a favourable eye yet it did tacitly acknowledged them. As a poem of the Nambokuchō period put it… `the dead before the entrance to hell, if they do not complain, shall not be heard`. In other words, even if a dead body was rolled up to the gates of the afterlife, if no complaint was raised about the death, then according to the public law this would not result in a criminal investigation. Just as the poem said, justice at the time was founded on the principle of `laissez faire`, and if no case was raised by either plaintiff, then public law had no authority to either launch its own investigation or to arrest any suspects.(p.42)

For the aggrieved, this meant that they could either rely on the public law or take the law into their own hands – the choice was entirely up to them. Of course, if one were to choose to practice `jiriki kyūsai`, and if the other side did not object, then there was nothing that the public law could do to intervene. This is to say, rather than describing the practice of revenge as being `sanctioned`, it would be more correct to say that it was `permitted`. While revenge may have officially been banned in medieval Japanese society according to public law, for society at large the practice continued both far and wide and was tolerated, which in itself was a dichotomy. From the Muromachi through to the Sengoku era, the public law was superseded by social contracts and practices, so much so that these practices soon became public law themselves. The fact that the legal officials of the Ashikaga Bakufu began to divert from the content of the Goseibai Shikimoku and gave their approval of katakiuchi is proof of this trend.(p.42)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed