Source: Sankei.jp

Source: Sankei.jp By way of comparison, the Consumer Tax Increase Bill of 2012 had a total of 129 hours devoted to debate, while the Post Office Privatisation Bill of 2005 saw approximately 120 hours of debate. Nevertheless, apart from an amendment included in the Bill by the Reform Party and Everyone’s Party for a third party organisation to examine materials designated as ‘secret’, the Bill was passed as intended by the Upper House on the 6th, and will be made law during the regular session of the Diet starting in January, 2014 (as the temporary Diet session ended on the 9th, the speed at which the Abe government moved to have the bill passed by the Diet becomes all the more apparent).

Since the introduction of the Bill to the Lower House on the 25th of October, the LDP and New Komeito numbers in both Houses have guaranteed the passage of the bills related to the re-organisation of Japan’s security apparatus without prolonged discussion, a situation that has infuriated the other minor parties and seen protests outside of the prime minister’s residence and the Diet building itself (the DPJ attempted to have a vote of no-confidence passed against the Abe government on the evening of the 6th, ultimately a futile gesture, but a registration of the level of dissent in the Abe government’s unilateral actions. Meanwhile LDP Party Secretary Ishiba Shigeru managed to compare the protestors to ‘terrorists’ in a less-than-well-considered blog entry).

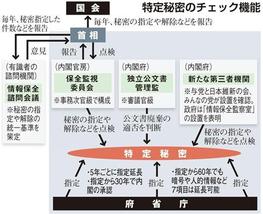

The public has clearly been rattled by the implications of the bill, as PM Abe’s own popularity took a dive for the first time since coming to government last year (according to the Yomiuri Shimbun’s own poll), dropping 9 points to 55% (in part this may also be because of dissatisfaction among the populace at the lack of benefits flowing on from Abenomics). While PM Abe has given his assurances that the Secrets Protection Act will be fairly and objectively applied, overseen by a regulatory body, suspicions that the Act will be arbitrarily imposed on any ‘inconvenient’ documentation regardless of whomever is supposed to regulate such decisions.

Where this may cause a problem for the Abe government is in how the Act is used. Japan well remembers its pre-war censorship, and anything that resembles an attempt at censorship will invite scorn on a government that tries to keep information from reaching its audience. Moreover, many of those radicals of the late 50s and early 60s will still remember the secrecy that surrounded the renewal of the US-Japan Alliance Treaty of 1960 by the Kishi and Eisenhower governments and the backlash this invited from the population. By creating enough discontent concerning the path Abe is taking, they may yet force the Abe government to strictly regulate the use of the Act and call into question the transparency of the government itself. The Abe government was elected on the back of dissatisfaction with the DPJ – that support could evaporate if the Japanese people believe that the LDP/New Komeito are trying to avoid accountability.

Certainly it appears that the Abe government, having established both an NSC and the laws to protect its operations, will seek to shift the domestic gaze to the economy and relations with China and the US. To allay the fears of the populace, it can’t hurt to remind them as to why the administrative changes were necessary in the first place.

In a related issue, on Monday Andrew Hunter of the Australian Fabians had another op-ed on the East China Sea. In his article, Hunter stated that “Ultra-nationalism was thoroughly discredited by its actions during the Pacific War but has returned as a force in Japan”, thereby attempting to draw a comparison between Imperial Japan of the 1930s and 40s and the current Abe government. Moreover, Hunter posed the following two questions in relation to China’s declaration of an ADIZ, writing… “It is true that China's precipitous actions have raised tensions. We have reason to be concerned. But why did we (meaning Australia) not react similarly in 2012 when the decision was made by Japan, without much trace of consultation, to nationalise the disputed territories? Why did we not express our disdain about the decision to nationalise the islands - announced on the anniversary of the Marco Polo Bridge incident that triggered the Sino- Japanese War? ”.

Hunter does acknowledge that ‘some’ level of consultation was made by Japan regarding its decision to nationalise the Senkaku Islands. Japanese journalist Tahara Sōichirō, in an article written on the 27th of March this year, wrote that former DPJ Deputy Foreign Minister Yamaguchi Tsuyoshi went to China on the 31st of August 2012 to discuss the then Noda government’s plan to nationalise the islands with Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs Secretary Dai Bingguo. Secretary Dai explained that while China’s position on the islands would not change, it would seek to work with Japan to manage the situation in the future. Unfortunately for Dai and Yamaguchi, the Noda government, in a secret deal with Ishihara Shintarō made on the 19th of August, had already decided to nationalise the islands and so Yamaguchi’s message from Dai came too late to change the outcome (PM Noda did mention Japan’s intentions to President Hu Jintao in a brief meeting between the two at the APEC meeting in Vladivostok on the 9th of September, to which President Hu voiced China’s strong opposition. Two days later, on the 11th, the Noda government formally announced that the islands had been nationalised by government resolution)*.

As to why Australia didn’t voice any objection to Japan’s nationalising the islands, it should be remembered that the negotiations on the islands were conducted between the Japanese government and persons who owned titles to the islands (a situation that the CCP never challenged). The Japanese government offered compensation to the owners in return for their titles, thereby using legal process as a means of acquiring territory. This was conducted within Japanese territory using Japanese domestic law, and was a transaction between private individuals and the government. Unless Australia implicitly wanted to back China’s claim to the islands by demanding an explanation from Japan on why it had nationalised property belonging to Japanese citizens, it chose not to raise it as an issue. Also, the return of Okinawa to Japanese administration in 1972 saw the US recognise Japanese jurisdiction over the islands. If Australia suddenly voiced its concerns about how Japan administered its territory, it would receive a very quick rebuke from the US. As Australia had only just signed an agreement with the US to host Marines in Darwin from 2012 onwards, it would look somewhat hypocritical for the pro-US Gillard Labor government to then suddenly lambast another US ally for defending its interests against an encroaching China.

China, on the other hand, did not consult with any regional or global state when it decided to announce its ADIZ. believing that it was in its right to do so according to its own logic. Rather than emphasizing the legality of its actions (in accordance with internationally recognised channels for registration of ADIZ), China simply announced the ADIZ as a fait accompli and expected surrounding nations to agree to it. It was a provocative move, designed to heighten rather than lessen tensions. While PM Noda sought to justify his actions by pointing out the potential for greater harm by having the islands administered by the Ishihara administration in Tokyo (a position rejected by China), it was an attempt to diffuse growing concerns in China over Japan’s intentions. If the Ishihara administration had offered to purchase the islands and this was accepted by the owners, it would be a transaction carried out according to Japanese commercial law which the government was bound to uphold. Unlike the CCP, the Japanese government does not exist separate to or above the rule of law, which made its position more difficult to negotiate.

This could have been recognised by the CCP, but instead it chose to use it as a catalyst to promote its own claims to the islands and denounced the Japanese government for attempting to change the status quo. This in turn may also have influenced the Australian decision not to criticise Japan, recognising that Japan had attempted to diffuse an already worsening situation, and that criticising Japan would be of little to no value in resolving the situation.

*The Asahi Shimbun also reported on that PM Noda had sent PM Secretary Nagashima Akihisa to China shortly after Ishihara Shintarō’s declaration to purchase the islands for the Tokyo Metropolitan Area during his visit to Washington in April, 2012. The article also claims that the breakdown of ‘silent recognition’ from China towards the plan by the Noda government to nationalise the islands came because of internal struggles within the CCP.

It should also be noted that PM Noda’s comments made on July 7th, 2012 indicated that his government was examining the purchase of the islands, not that it would purchase the islands. As to whether this was deliberately chosen to occur on the anniversary of the Marco Polo Bridge incident so as to provoke China, PM Noda was visiting Iwaki City in Fukushima Prefecture on the day the comments were recorded. Whether Noda, in conversation with Ishihara, made a promise to Ishihara in private conversation to mention their negotiations on this specific day if asked by the media seems farfetched, although not implausible.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed