Source: guardian.co.uk

Source: guardian.co.uk Having ensured that the world was paying sufficient attention, North Korea then began to take increment steps towards the ‘appearance’ of preparing for war – closing Kaesong industrial park to South Korean workers, closing its northern border to Chinese tourists, declaring to diplomats in Pyongyang that it couldn’t guarantee their safety, declaring to any foreigners in South Korea that they should evacuate the peninsula as there was a possibility of thermonuclear war breaking out at any moment, moving two missiles to its eastern coast, and making overtures towards restarting its long dormant nuclear reactor at Yongbyon. As has been pointed out by commentaries on this situation, North Korea has not made any major re-deployments in its troop configurations, there has been no added activity from either its air force or naval forces, and residents of Pyongyang have continued to perform their regular activities without any major civilian evacuation exercises.

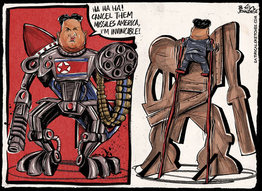

South Korea has meanwhile stated that according to its own intelligence, North Korea is planning to initiate some form of missile test over the next week. At the same time it also reported that North Korea might conduct a fourth nuclear test just to up the ante with the US and UN (before later retracting that statement). As for why North Korea may be behaving in this manner, there have been no definitive reasons put forward – speculation has gone from a possible coup against Kim Jong-un which has led Kim to try to consolidate his position and demonstrate his suitability as leader, to a dangerous game of one upmanship being played by the North Korean regime in order to force the international community to agree to its demands and reduce the severity of sanctions.

All of these analyses may be right, but only time will tell which was the most prescient. North Korea would not engage in upping the ante unless it felt humiliated (which the UN sanctions would have triggered, given that they were supported by China), and desperate to gain some leverage, any leverage, in its relations with the outside world. North Korea is probably well aware that any unilateral act by it against another state will invite retaliation, yet it may risk such retaliation if the Kim regime believes it can profit from it.

As for the reaction of other states in the region, all have urged calm and restraint in dealing with North Korea, yet clearly the region no longer has the patience to allow North Korea to keep issuing threats and expect no response. South Korea has certainly run out of patience, and has made clear that any indication from the North that it is planning to attack the South will prompt a preliminary strike against North Korean defence assets. The US has also put in place a number of measures aimed at protecting its allies in Northeast Asia, such as deploying B-2 stealth bombers and F-22 5th generation fighter aircraft to South Korea, together with the deployment of Aegis class frigates and a THAAD anti-ballistic missile system to Guam. Indeed, every time the North made another threat, the US responded by placing yet another asset near the Korean peninsula.

While some criticism has been directed at the US for taking a more provocative stance towards the North, really it has no other choice. Successive US administrations have tried bilateral dialogue, multilateral dialogue, aid initiatives, assistance initiatives (medical and energy production), sought advice from China and Russia on dealing with North Korea, and has sent a number of envoys, including former presidents, to negotiate with the North. The sum total of all of this effort has been no change in the North’s stance and an increase in belligerent rhetoric, not to mention open defiance of the UNSC in conducting nuclear tests and missile launches into the East China and Japan Seas (Link). Since the North has time and again shown that it is not prepared to cooperate with the US, the US is simply ensuring that no matter the North eventually tries, it will fail.

Meanwhile Japan has taken its own measures to ensure its defence against any provocation from North Korea, putting in place a number of PAC-3 batteries to protect Tokyo from either North Korean missiles or the debris from such missiles should they break up over the Japanese archipelago. Interestingly enough, PAC-3 batteries only have a range of 20 kilometres as they are primarily designed to hit incoming missiles. The problem with this is that even if they do manage to bring down a missile, the debris from the explosion can still fall on those below. If North Korea were to load one of its missiles with a nuclear warhead, even if the warhead fails to detonate, its cargo would still be radioactive enough to contaminate an area 20 kilometres around the PAC-3 battery.

As such, the PAC-3 is more of a ‘last resort’ measure should all other measures fail. The first of those measures are early warning relays from US defence satellites stationed above the Korean peninsula. Should a launch be detected, these satellites will relay the rocket location to both US and SDF units based in South Korea and Japan. Such information is then transmitted to US and JMSDF Aegis frigates stationed in the East China and Sea of Japan areas in order to attempt a low altitude interception from the launch site and before the North Korean missile reaches its apex. If this is unsuccessful, a high altitude interception can be attempted, although the preferred method is to wait for the missile to begin its descent so that it may again be intercepted at a lower altitude (thereby raising the probability of interception and destruction). If none of these succeed, then the SDF will use its PAC-3 batteries (加藤健二郎、いまこそ知りたい:自衛隊のしくみ、日本実業出版社、東京、2004年、130-131).

As PM Abe has already given approval for Japan’s defence measures to take preliminary action should any North Korean missiles head in the direction of Japan, Japan has taken the necessary precautions against the threat coming from North Korea (Link). Of course, should any North Korean missiles head in the direction of South Korea, President Park Geun-hye has given her approval for a retaliatory strike against command and control centres in the North. As other blogs have speculated on the consequences of this I will leave it to them to explain possible developments, but it suffices to say that North Korea will gain nothing from this level of antagonism (Link), and might find itself completely cut off from any and all ties with the outside world. That might precipitate an internal collapse (no fuel and no food, especially after a harsh winter in the North, could lead to mass defections), but nothing is certain in relation to North Korea’s future.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed