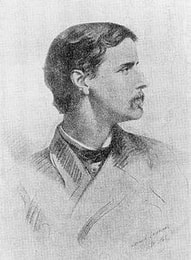

Portrait of AB Mitford, 1865, by Samuel Lawrence

Portrait of AB Mitford, 1865, by Samuel Lawrence The above memoir concerns the personal experiences of the British diplomat Algernon Bertram Freeman-Mitford (1st Baron Redesdale), who in the Autumn of 1866 (Keiō 2) arrived in the port city of Yokohama to take up a position as a second secretary within the British legation. It was during that first encounter with Japan by Mitford that he came into contact with Ernest Satow, himself a British diplomat, and the two of them would remain life-long friends. Mitford himself was born in February of 1837 (Tenpō 8), and was six years older that Satow (he was around 28 when he arrived in Japan).

Mitford himself admitted that his reason for writing a memoir of his experiences in Japan stemmed from the fact that for many years he had not spoken to anyone about what he saw and heard during his residency in Japan, and that after the passage of 50 years many of those whom he knew in Japan, and who had played such a pivotal role in the opening of Japan to foreign influence and in the establishment of Japan as a modern state, were already starting to pass away. So he endeavoured to write down, in as much detail as he could, his reminiscences of Japan.

Mitford held Ernest Satow in very high regard, and praised Satow as the principal reason why he was able to experience so much of the historical events that punctuated the early years of foreign diplomatic activity in Meiji Japan.

Mitford arrived in Yokohama by ship in October of 1866, and spent four years at the forefront of Japan’s emergence into the modern world. His arrival in early October coincided with a cold front over much of north-east Asia, so when his ship set out from Shanghai it met with some rough seas and both crew and passengers were very relieved when they finally dropped anchor just outside the port of Yokohama. At the time of his arrival the port city was being battered by heavy rain and strong winds, and at the customs house on the wharf water ran through the building as though it had been built on a river. The customs officials themselves wore fairly non-descript clothing (kimono) with two swords at their hip, with lacquered caps and grass mantles.

For the first two to three days, until lodgings were prepared, Mitford stayed at the official residence of Minister (re: Ambassador) Harry Parkes. The residence itself was located near the coast, and was a one-storey building. Mitford wrote that on his first night at the residence, possibly as a reflection of the bad weather that accompanied his arrival, discussions at the dinner table were somewhat gloomy, focusing on the death of ‘Richardson’ (in the Namamugi Incident), the assassinations of Baldwin and Bird (by shishi in the streets of Yokohama), and the attack that occurred against the British legation during the residence of Ambassador Rutherford Alcock and Captain Neale by ‘rōnin’. Mitford wrote that his first nights in Japan were spent listening to the wind howling through the ambassadorial residence, rattling windows and doors, which made him grab a nearby pistol in fear that the residence was under attack. Apparently he wasn’t the only one to think this, and that the hallway of the residence was filled with diplomats bearing arms in anticipation of an assault by ‘rōnin’.

Mitford’s first night in Japan was also accompanied by an earthquake, which added to the fears of the diplomatic staff in the residence. However the danger soon passed, and the following days were blessed by good weather, so much so that he was able to see Mt Fuji capped in snow and in all of its glory. Mitford also spent the first few days in Japan walking around Yokohama, both in and outside the city, with Satow. As it was Autumn, the fields outside the city were brimming with ripened rice plants, along with the hills around the city being dotted with red and gold hues and deep green pine, cypress and bamboo forests at the foot of the hills.

Mitford points out that in 1866, with the political situation in Japan so uncertain, a rivalry broke out between Ambassador Parkes and the French Ambassador Leon Roche. He proceeds to describe the physical characteristics of Parkes, noting that he was a short man, with thinning hair, but of cheerful disposition. He notes he had a large head, with a broad face, so that his body and head “did not appear in proportion to one another”. He also says Parkes was ‘fearless’ and never showed any sign of weariness, but was excitable and quick to anger. He then goes on to describe Parkes’ time in the East, noting he had been sent out to China at the age of 13 in 1841, had studied Chinese vociferously, and had performed the role of interpreter, embarking on dangerous journeys into the interior of China from time to time. Parkes was appointed as ambassador to Japan when he was 38, and Mitford met him a year after he had assumed that position. Parkes apparently regretted the fact that his education had been abruptly interrupted in his youth, and so spent much of his life trying to make up for this by engaging in reading in his spare time (which was little, given Parkes was a very active character). Mitford believed that Parkes’ greatest short-coming as a diplomat was the fact that he could not speak French.

Mitford says that Parkes and Roche were deeply jealous of one another, noting that when war broke out between the Bakufu and regional daimyo, they were both backing “the wrong horse”. In Parkes’ case, he had the extraordinary fortune of having Ernest Satow in his employment. Satow had studied the traditions and folk history of Japan in detail, understood the position occupied by the Shogun, and knew that the Emperor was the original head of the nation. Not only this, he possessed fluency in Japanese, was intelligent and able to speak plainly, which enabled him to become an acquaintance to many of the most influential people in Japan. He was also young, which would be a great advantage to the ambassador in forging ties with the Japanese state.

One other person that Mitford praises for his deep knowledge of Japan was Thomas Glover (a merchant residing in Nagasaki, and who provided weaponry to the anti-Bakufu forces). Ambassador Parkes regarded Satow’s advice as exemplary, and his advocacy led weight to Satow’s suggestion that Britain back the daimyo forces absolutely. Roche, on the other hand, was firm in his support for the shogunate, and so continued to provide support to that institution despite the fact it was gradually growing ever weaker. Parkes was particularly incensed when he found out that Roche had brought out from France army instructors to instruct the shogunal forces, and so resolved to bring British naval officers to Japan to educate the daimyo forces. Mitford therefore believed that the development of the Japanese army and navy came about because of the personal dislike between Parkes and Roche.

Mitford says that Roche lent his hand to shipbuilding facilities, port facilities, and weapons manufacturing, which were all areas he expected France would have a monopoly. Yet the development of all of these elements depended on the shogunate remaining in power. Roche’s audacious plan led to fierce diplomatic debates, so much so that Ambassador Parkes regarded Roche with a lot of suspicion. Mitford states that the Tokugawa were to be congratulated on being able to provide some 200 years of stability for Japan, but the rot within the institution of the shogunate started from the third Shogun Iemitsu onward.

Mitford stated that after a week he was able to move into his own abode, made of plain wood and paper. He (with a great amount of sarcasm) stated that the house itself was ‘a little bigger than a doll’s house’, with a small garden with a number of small trees growing in it. Mitford lived in one of three connected residences, the others being occupied by Ernest Satow and Dr William Willis. The residence was in the foreigner’s quarter, somewhat separated from the city (or town) of Yokohama itself. Willis had some difficulties with his house, given that he was a large man, and his coming and going from such a small abode was a source of constant wonder to Mitford. As a house warming party, the three diplomats invited a number of members of the 9th Regiment and three or four ‘geisha’. The food supplied was Japanese in origin, and the revelry lasted until midnight.

The Great Fire of Yokohama:

The time spent in the foreigner’s quarter was brief, as on the 26th of November Mitford said he was woken by a sharp gust of wind that blew through one of the doors of the residence. He jumped out of bed without time to dress (mainly because all of his furniture and luggage had only been brought into the residence the night before and remained unpacked). He had enough time to shave before a Chinese servant came in to tell him that a large fire had been spotted some 2/3rds of a mile away. Mitford believed he had enough time to dress and then venture out to look at the fire, unaware of the sheer speed at which a fire could spread through a town built primarily of wood.

After shaving and dressing, which consisted of his trousers and a thick overcoat, he went outside, only to discover that a fierce wind had intensified the fire which had spread to the neighbourhood around his residence. Mitford had a pet dog which he attempted to bring outside with him, however spooked by the noise and chaos of people running about, the dog ran back into the building. Mitford discovered the bones of the dog the following day in the ashes of a Western chest of drawers. In the space of an hour, the neighbourhood that Mitford was in disappeared, with a fierce wind continuing to blow, causing the fire to jump from roof to roof and devouring everything in front of it, leaping hundreds of yards in an instant.

One of the curious things that Mitford noticed about the fire was that unlike fires in London, which were accompanied by sounds of wood cracking, popping and collapsing house frames, this fire just burned everything up, much like the wick of a candle. Houses that had been standing just moments before were reduced to ash in a matter of minutes with nothing but the red glow of heated roof tiles left behind. Such was the ferocity of the fire that no buildings, whether wooden or brick, survived unscathed, and the entire town would have been swallowed up if the wind hadn’t abated around midday. Mitford observed that if a fire such as that in Yokohama started in Edo, it would have raced off in all directions and reduced the city to ruins.

Mitford described a great many lives being lost in the fire, noting that close to his residence bodies had been laid out in rows and which were mostly unidentifiable. He noted that most of the victims of the fire lived in the area that it started, the Gankirō (岩亀楼) district, famous for its houses of prostitution. Some of the bodies discovered half burned had been pulled from a well, where a number of women had thrown themselves in a desperate attempt to escape the fire. Mitford was left with only the clothes he had managed to throw on (including his shoes and socks), however those whose homes survived the blaze showed generosity to those left without accommodation. Admiral Sir George King sent Mitford six shirts along with a letter that Mitford treasured for the rest of his life.

Rebuilding and relocating

Mitford writes that a few days before the fire, serious consideration was given by Ambassador Parkes to relocating the British mission to Edo, to the site of the original mission headed by Alcock and Neale on Goden-yama which overlooked the ‘notorious’ Shinagawa village. The location apparently had fine views, but it had been abandoned after being attacked and destroyed by ‘rōnin’. Mitford relates that Itō Hirofumi (whom he calls ‘Lord Itō) was one of the young rōnin allied to those who attacked the mission, and that the British mission was aware of his activities before he became a minister of the state. Itō was a good friend of Britain by the mid-1860s, and so when he was teased about his former life by the British diplomats he didn’t deny it but merely laughed.

Parkes was of the view that since Japan was a nation well disposed towards Britain, and that since Parkes had been sent as the representative of the British government despite not being the actual leader of his nation, the British mission had in all respects abandoned its right to property within Edo, which was in fact the seat of government. The situation was thus an ‘anomaly’ to what should otherwise be the proper state of affairs for diplomatic missions. Mitford agreed, and so the two of them set out for Edo in order to find a building that could function as a permanent site for a mission.

The site they settled on consisted of two long, single storey buildings (which by the early 20th century were almost falling down), with one of the buildings set aside for official duties and the other for personal use. The site itself was located a little removed from Sengakuji, site of the graves of the 47 retainers. There was a guard house next to the gate entrance, into which would be placed soldiers from the 9th Norfolk Regiment, dispatched from Yokohama. Mitford wrote that most Japanese he spoke to were surprised to learn that English troops had once protected Yokohama from their camp at Yamate, but this was the reality at the time of the opening of the foreign ports.

The British mission was also protected by a large number of guards, known as the “Betsu-te gumi”, most of whom were drawn from the ranks of lower class samurai and charged with the protection of the mission. However their principle task (according to the British diplomats) appeared to be to spy on the mission. Mitford reasoned that, under the Bakufu rule, no country in the world engaged in spying as much as Japan, and spying was considered to be more of an art than an occupation. Officials were never allowed to operate by themselves, and would always be shadowed by a “metsuke”, with the same thing going for foreign diplomats.

He also describes a number of small, single storey houses that were built just below Sengakuji, and which he says were poorly constructed. They each featured a number of iron stoves, which were virtually useless as they would glow bright red if fires were lit inside them and fill the room with the smell of burning iron. As such, it was better to endure the cold from the wind blowing in threw gaps in the windows and doors and down the long corridors than to light any fires. So for the first few nights, Mitford said that he and others tried to endure the cold as best they could, and went to bed early in an effort to try and stay warm, but to no avail. On the first night, Mitford was awakened by the sound of a bugle, and just like his experience in Yokohama jumped up out of bed pistol in hand expecting to have to repel intruders. On making enquiries, Mitford was informed that it was merely the guard making revelry, and so returned to bed to attempt to stay warm.

Both Mitford and Satow felt that the small housing they were forced to reside in, under the gaze of the Betsu-te-gumi, made it a little like being imprisoned. Hence both of them petitioned the ambassador to give them permission to move to a nearby temple. The ambassador was all for it, however given their restricted movements, it would take an unusual approach to get the Japanese authorities to agree to the measure. Hence the first thing Mitford and Satow did was to rent a section of a nearly temple known as Monryō-in. It was a small temple located around 100 yards from the mission on top of a hill, and had spectacular views of Edo bay. Mitford and Satow thus became the first foreigners to be permitted to live in an area outside of a designated zone. When they went on afternoon walks, even when they went the nearby mission, they were not able to escape the gaze of the Betsu-te-gumi. If they had been allowed to wander freely, they would have been able to interact more with the Japanese townspeople. Every now and then they would hear drunken bugle playing from the barracks attached to the mission, but it was always a long way off so they didn’t give it much thought.

Years later Mitford paid a visit to the location of the temple, but found that nothing was left of the house that he and Satow lived in, and that the garden was overgrown with weeds and grass, which he said was “disappointing”.

Mitford and Satow tried to live as frugally as possible, down to the smallest farthing. Instead of hiring an in-house cook and spending money on cooking ware and utensils, they had their meals brought to them from a nearby Japanese kitchen. These meals mostly consisted of rice and fish, occasionally supplemented with either chicken or duck meat. On days when the weather wasn’t particularly good and fishermen weren’t able to fish, the kitchen owner would come around to apologise, bringing with him bamboo root and seaweed. Both Mitford and Satow would venture out together, although as Mitford was the senior, he was the one who had to write reports about their activities, but in actuality it was Satow who wrote the reports and offered advice.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed