Photo:fxya.blog129.fc2.com

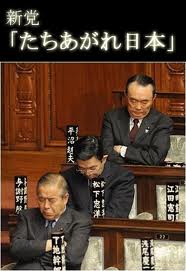

Photo:fxya.blog129.fc2.com At a press conference to announce his retirement as governor, Ishihara declared that he had reluctantly decided to run for a federal seat in order to break the power of the bureaucracy and bring about constitutional reform (J). Ishihara also revealed that he was prepared to negotiate with Hashimoto Toru’s Reformist Party and the Your Party of Watanabe Yoshimi so as to form a “third alternative” (J) to the two-party rule of the DPJ and LDP (prompting Mizutani Takashi of the LDP to wonder whether any other party could agree with the platforms put forward by Ishihara) (J). In order to achieve his new-found political aim, Ishihara negotiated with the 5 members of the Sunrise Party (たちあがれ日本, led by Hiranuma Takeo), a party that he had helped form in 2010, who thereafter agreed to rename themselves the “New Ishihara Party” (with the name change take place in early November 2012. This decision was apparently made so as to avoid having political funding cut off which would be a consequence of leaving the current party, as happened to members of Ozawa Ichiro’s People First Party – J).

The decision by Ishihara to involve himself in federal politics has raised eyebrows among Japan’s political commentators, who have (together with members of the DPJ and LDP) pointed out that Ishihara and the Sunrise Party (insert your own 70s funk band parodies here) have virtually nothing in common with either the Reformist Party or the Your Party platforms – indeed, Hashimoto and Ishihara are at opposite ends of the argument over whether Japan should join the TPP (Hashimoto favours it, Ishihara opposes it, although Hashimoto himself has said that, in essence, the Reform Party agrees with Ishihara’s ideas, just not those of the Sunrise Party (J and J. The Shukan Asahi has also reported that members of the Sunrise Party weren’t too keen on linking with the Reformists either (週刊朝日「石原慎太郎―ひとりぼっちの決断」11月9日号頁18). The problem with Ishihara, it seems, is that his rhetoric has yet to resemble a plan. At a time when the nation is dealing with questions over energy dependency, an aging society, how to re-invigorate the industrial sector and kick start the economy, Ishihara’s comments on China, the manner in which he completely washed his hands of the whole Senkaku Islands purchase affair (a problem that he himself started), and his rhetoric about constitutional reform do not resonate all that well with the population at large.

Ishihara is of another time and generation – Hashimoto Toru knows this, as does most of the electorate (indeed, the average age of members of the Sunrise Party is 72 (J). They offer few solutions to Japan’s present woes and reiterate many old slogans that have long since lost popular appeal). His advocacy of Tokyo, including putting it into the run to host the 2020 Olympics despite continuing problems from the Great East Japan Earthquake, was seemingly for his own benefit, with Deputy Governor Inose Naoki left to assemble the framework for many of Ishihara’s pronouncements. What is more, as Deguchi Naoaki has explained (J), even if Ishihara’s new party managed to link up with the Reform and Your Parties, all three combined would only have 15 seats in the House of Councillors, compared to 88 for the DPJ and 83 for the LDP, nowhere near enough clout to ensure that they control the balance of power in the upper house. Shukan Asahi predicts that Ishihara’s new party would gain no more than 12 seats in the next House of Representative’s election, making it all but irrelevant to most voting in the lower house (週刊朝日「石原慎太郎―ひとりぼっちの決断」11月9日号頁23).

Given the fact that Ishihara offers few solutions, is linked to a party for whom fossilised is an apt description of its policies, and has a record of antagonising Japan’s neighbours (and the US) for no positive gain, what can the Japanese populace expect from him? According to Yamazaki Hajime, this amounts to three things; Criticism of the tendency of politicians to become too concerned with minutiae and lose sight of the “big picture”, priority of regional security issues, and criticism of the close ties between the main parties and the bureaucracy (J). In other words, Ishihara could function as a bête noire for the government, making life more difficult for either the DPJ or LDP in budget estimate hearings or regular Diet sessions by questioning the reasoning behind funding or policy decisions. This would reduce him to little more than a cranky old commentator railing against whichever major party is in power (so not really different to his last three years as governor), yet this is certainly not what the populace needs in a viable alternative third party. Ishihara's time as a potential reformer has past.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed