Source: www.yourepeat.com

Source: www.yourepeat.com During the end of year period there was a great deal of activity in Japan in preparation for 2015, including PM Abe’s address at Ise Shrine where he declared that he intended to issue another statement on the 70th anniversary of the end of WWII, and that this statement would be in keeping with those of previous PMs including Murayama Tomiichi, along with a later announcement of budgetary arrangements for 2015 that included the largest increase in defence spending in postwar Japan (for the third year in a row. This is mainly because of the need for purchases of the F-35, a new fleet of P-1 surveillance aircraft, amphibious vehicles, and preliminary construction of facilities at the designated US forces base at Henoko in northern Okinawa) (J).

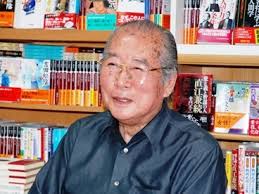

Yet despite these developments, I wanted to look at a more personal matter that I’ve been meaning to bring up for some time. It concerns the work of author Dōmon Fuyuji (otherwise known as Ōta Hisayuki), and the contribution I believe he has made to a better understanding of Japan’s past and the drama contained within it. I’d hazard a guess that Dōmon is not well known outside of Japanese historical circles, but his writings and essays do deserve a wider audience given the way in which he is able to present quite complicated historical events in clear, direct prose.

My first contact with Dōmon occurred during my final years in university, when I was looking to find Japanese language material that would explain events in Japan’s past in language that I, a Japanese language novice, would still be able to understand (with a little help from a dictionary). I managed to obtain a copy of a reference book detailing the ‘business savvy’ of various Sengoku era generals edited by Dōmon. While the subject matter was fairly frivolous, Dōmon’s use of clear, modern prose, and his ability to illustrate a point that highlighted the human character of Sengoku generals, impressed so much that I vowed to look up more of his work when I had the chance.

That chance came later while I was living in Japan. It was while I was there that I learned that Dōmon had begun his career as a bureaucrat in the Tokyo municipal government, eventually working his way up to speech writer and secretary to the governor. He was in his early 30s when turned his hand to writing historical novels, covering periods from the Kamakura era through to the Meiji Restoration. While other writers of historical novels, in order to increase the ‘historical credentials’ within, choose archaic terms and old linguistic forms to pad their text, Dōmon eschews the more ‘traditional’ approach to historical novels in order to promote the story itself.

Purists might deride this as pandering, but the fact remains that it has made Dōmon famous, almost (but not quite) to the same level as Shiba Ryōtarō (a contemporary, incidentally, of Dōmon). Dōmon regularly features in NHK documentaries on historical figures of note, and his opinion is sought out by editors keen to get a sense of prominent figures of Japan’s past. I’m currently reading Dōmon’s novel of the life of Kuroda Kanbe’ei (Nyosui), which coincided (possibly not by coincidence) with an NHK Taiga drama on the very same individual. As per usual the writing is very straight-forward, and Dōmon obviously has a lot of admiration for his subject. He has previously described Kuroda as being one of the most brilliant strategists of the Sengoku era who never attained his true potential, and portrays Nyosui’s cunning against the more ‘honest’ character of Nyosui’s heir Nagamasa (‘honest’ being a very subjective term in relation to Nagamasa).

In sum, Dōmon is well worth a read for those with Japanese language ability, and is certainly very useful for expanding one’s knowledge of historical characters. His exhaustive bibliography alone will consume many of my reading hours for years to come.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed