kyoto-brand.com

kyoto-brand.com There are still studies, however, that pop up from time to time that provide a new perspective on the whole phenomenon of religiously sanctioned violence and its effect on society. The chapter that follows is from just such a study.

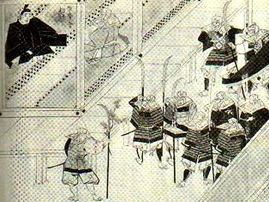

The mountain peak battle of Chōji

In the latter part of the Heian period at the head temple of the Tendai sect of Buddhism, Hieizan Enryakuji, internal factional battles regularly broke out which were accompanied by the appearance of armed temple followers. These were the so-called “Sōhei” (literally, warrior monks), and were widely regarded as a symbol of the destruction of the ‘Buddhist Law’ (Buppō) that characterised this period. At the same time, and in the same way, the temple of Kōfukuji located in Nara also had its own Sōhei , and these two major temples exercised a powerful influence over the religious world of their time (this division in power between Enryakuji and Kōfukuji was known as the Nanto Hokurei, or 南都北嶺). (p.16)

As an introduction to this subject, I will pay attention to an incident that took place in the 1st year of Chōji (1104) which is a typical example of the type of internal conflict witnessed at Enryakuji during the Heian period. Enryakuji comprised a large number of estates that spanned across the Mt Hiei area. The three principle estates of Enryakuji were known as Tōdō (the Eastern Tower), Saitō (the Western Tower), and Yokawa. The estates were not determined by geography, but functioned more as a political entity in which meetings known as Shūe took place. In order to preserve their territory and right to use the labour found therein, each ‘tower’ maintained an independent political stance and acted in their own interests. The temple complex of Enryakuji, which comprised these three towers, was certainly not monolithic. (p.16)

The incident of violence detailed here occurred as a result of a clash between the Eastern and Western towers. The incident itself reveals in stark detail the type of armed conflict undertaken by monks in temple complexes at the time, and clarifies the role played by groups of monks (known as a Daishu) and their ties to ‘Akusō’ (literally, evil monks, 悪僧), a term often used at the time to describe such characters.(p.16)

In the 7th month of the 5th year of Kōwa (1103), Fujiwara no Tadazane, the Minister of the Right to the Imperial Court, issued an expulsion order against the monks of the Western tower of Enryakuji (this information is derived from the Denryaku, a diary maintained by Tadazane dated for the 22nd day of the 7th month). The Daishu of the Western tower was spurred into taking action against Tadazane, although the actual course of action is unclear. From the 3rd month of the following year, diary entries reveal the increase in sporadic fighting between the Eastern and Western towers. It did appear to Tadazane that the age of the downfall of the Buddhist Law had arrived, given the prevalence of acts of arson and the destruction of monk lodgings by either faction. It is certainly likely that Tadazane’s expulsion order of the previous year played a role in sparking the feud between both towers. (p.16-17)

While this was going on, the background story to the conflict between the towers began to reveal itself. In the 6th month of the 1st year of Chōji, a “Daishu” submitted a formal request to the Court that Gon no Shō Sōzu Jōjin (貞尋) be punished by being sentenced to exile from the temple complex (it is not clear at this point to which Daishu the diary was referring). The Daishu fingered Jōjin as being both a conspirator and agitator in the recent disturbances between the towers. When Jōjin managed to escape punishment despite confirmation of his guilt, mainly as a result of Court largess towards Jōjin, the Daishu continued to demand that he be punished. (p.17)

At the same time, the Daishu charged that a monk known as Keichō (慶朝), who at the time was the head of the Tendai sect, was in cahoots with “that evil monk Jōjin” and retaliated by destroying Keichō’s living quarters. Keichō was a monk affiliated with the Yokawa tower, and fulfilled a dual role (in addition to being head of the sect) as administrator of Yokawa’s territory. On the other hand, Jōjin, Keichō’s co-‘conspirator’, was affiliated with the Western tower. Since, as a result of the request, Jōjin was denounced and Keichō had his quarters demolished, the Daishu referred to above was not that of the Yokawa or Western towers but was from the Eastern tower. The conflict from the previous year between the Eastern and Western towers had thus spread to the Yokawa tower and intensified. (pp.17-18)

An attack on the head of the sect was obviously a problem for the Court, so in the 10th month the Court ordered that a Sōgō (僧綱) be convened in order to investigate the incident. A Sōgō was a meeting of various officials that transcended sect divisions and whose function was to regulate and administer the activities of monks and nuns. Whenever a problem emerged between monks, the Court took it upon itself to convene a Sōgō. Diary entries of the time note that the Sōgō would be ordered to clarify whether the disturbance affected the overall structure of Enryakuji or whether it was the result of the actions of a limited number of individuals. If the disturbance resulted in recourse to arms, the Sōgō was also authorised to dispatch warriors to the entrance to the mountain temple complex at Sakamoto (in modern Shiga prefecture). (p.18)

Unfortunately no historical records remain that explain how this particular disturbance was resolved. However, from the 12th month of the same year (Chōji 1) through to the 1st month of Chōji 2 (1105) a new disturbance broke out between Enryakuji and the temple complex of Onjōji (Miidera). This new conflict obviously demanded Enryakuji’s full attention, and so it appears that the internal conflict between the Eastern and Western towers was resolved before tackling the feud with Onjōji. As Keichō resigned from the position as sect head in the 2nd month of Chōji 2, we can surmise that he took responsibility for bringing the internal dispute to an end and withdrew.(p.18)

This particular disturbance, which is referred to in the Chūyuki diary as the ‘mountain peak war’, features a range of individual monks apart from those already referred to here. There are certainly many who considered these monks to be typical examples of “Akusō”. As revealed at the beginning of this chapter, these individuals, whose existence within the temple complexes of medieval Japan was so entwined with violence, certainly garner our interest as Sōhei.

However the fact that these individuals were referred to as “Akusō” does not mean that diarists simply assigned to them a pejorative nuance that stemmed from an act of violence. In many instances, the actions undertaken by these individuals were sanctioned by their Daishu. In order to ensure that one does not come to conclude that Akusō were by nature outlaws, it is necessary to outline their relationship to the Daishu. This chapter will explore the various theories that have emerged regarding the “Akusō” that appear in the “mountain peak war”, and will explore the peculiarities of the age that gave rise to such figures. (pp.18-19)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed